Overweight and obesity have emerged as a global “epidemic.” By 2022, it was estimated that 43% of adults aged 18 and older were classified as overweight, with 16% classified as obese (1). The average body mass index (BMI) of the global population is gradually increasing. With the average body mass index of the global population gradually increasing, overweight and obesity have become a public health crisis. It has placed a huge burden on the healthcare and economic systems of both developed and developing countries (2). According to the World Obesity Alliance (2024), the fight against obesity requires significant financial investment, and by 2035, high BMI will result in a reduction of more than $4 trillion in the global economy, nearly 3% of global GDP (Gross Domestic Product) (3). Overweight and obesity also bring poor physical and mental health to patients, they not only increase the risk of type 2 diabetes and heart disease, affect bone health and reproductive system, but also may raise the risk of certain cancers (4). In addition, people who are overweight and obese show poorer mental health outcomes (5). Extensive epidemiological research has established a link between high body weight and deteriorating mental health, particularly concerning depression and subclinical depressive symptoms (6). Psychological stress induced by weight stigma and discrimination can lead to psychological distress and may, in turn, impede weight management efforts (7).

The main treatments available for overweight or obesity are nonoperative management and bariatric surgery, with nonoperative management being a multimodal approach that includes dietary changes, increased physical activity, behavioral changes, and medications (8). Among them physical activity is an effective means of weight loss and health management with fewer side effects and adapted to most populations., it can prevent weight gain, reduce weight loss, minimize weight regain after weight loss, and reduce the chances of developing chronic diseases (9). Research shows that exercise requires long-term persistence, and affective responses may be predictors of exercise adherence (10). Feelings of pleasure and enjoyment are key factors in adherence to an exercise program, and an increase or decrease in pleasure may contribute to the likelihood of forming positive or negative exercise memory traces. This in turn affects their subsequent decisions to participate in, persist with, or withdraw from exercise (11). William et al. also mentioned in his study that the core potency response (i.e., pleasure/displeasure) experienced during exercise has been identified as a key determinant of future physical activity behavior, especially for overweight or sedentary adults, who are most in need of interventions to enhance adherence to exercise programs (12). Some obese and overweight people may have difficulty maintaining long-term adherence due to weight stigma, self-rejection, or low - and moderate-intensity exercise that is monotonous and non-stimulating, and thus stop exercising after a period of exercise because they cannot stick to it (13, 14). This led us to consider the relationship between obesity and emotional response to exercise. What kind of exercise can give obese and overweight people a good sense of enjoyment and affective response, so that they can keep exercising?

When it comes to physical activity modality choices, there is a wealth of research that proves that high-intensity interval training (HIIT) and moderate-intensity continuous training (MICT) are effective modalities of exercise for improving body composition (15, 16). They are effective in improving health and fitness parameters (17, 18). For example, one mate-analysis showed that low-volume HIIT (LV-HIIT; i.e., ≤5 min high-intensity exercise within a ≤ 15 min session) can have similar effects on cardiometabolic health and body composition as MICT and high-volume HIIT, such as in terms of blood pressure, fat mass and waist circumferences (19). It is also proved that HIIT once a week, even with low weekly activity, can improve cardiorespiratory fitness, body composition, and blood pressure in overweight or obese adults (20). However, the research on assessing affective or pleasurable responses to HIIT and MICT has been largely ambiguous, no matter what kind of population they are in (21). For example, study by Niven et al. concluded that compared to MICT, HIIT is experienced less positively but post-exercise is reported to be more enjoyable (22). While study by Oliveira et al. (23) suggested that HIIT may garner equal or more positive psychological responses than MICT (23). In present review we attempted to update more precisely describe participants’ affective responses to HIIT and MICT. At the same time, HIIT leads to similar or better physiological and biochemical effects than MICT, but takes less time (20, 24, 25). This provides a new direction and a new way of thinking about the barriers to physical activity in overweight or obese patients, i.e., insufficient time to maintain physical activity levels, and is a good prescription for a “short and fast” way to promote physical activity (26).

Some previous systematic reviews and meta-analysis investigated affective and enjoyment responses to HIIT and MICT have not distinguished obese and overweight people from the general population. Thus, the purpose of this study is to try to find which type of exercise brings better emotional and pleasurable experiences to obese and overweight people and whether HIIT is a better form of exercise for obese people than MICT. Through a systematic review and meta-analysis of the existing literature, to provide new ideas for the selection of exercise prescription for weight loss.

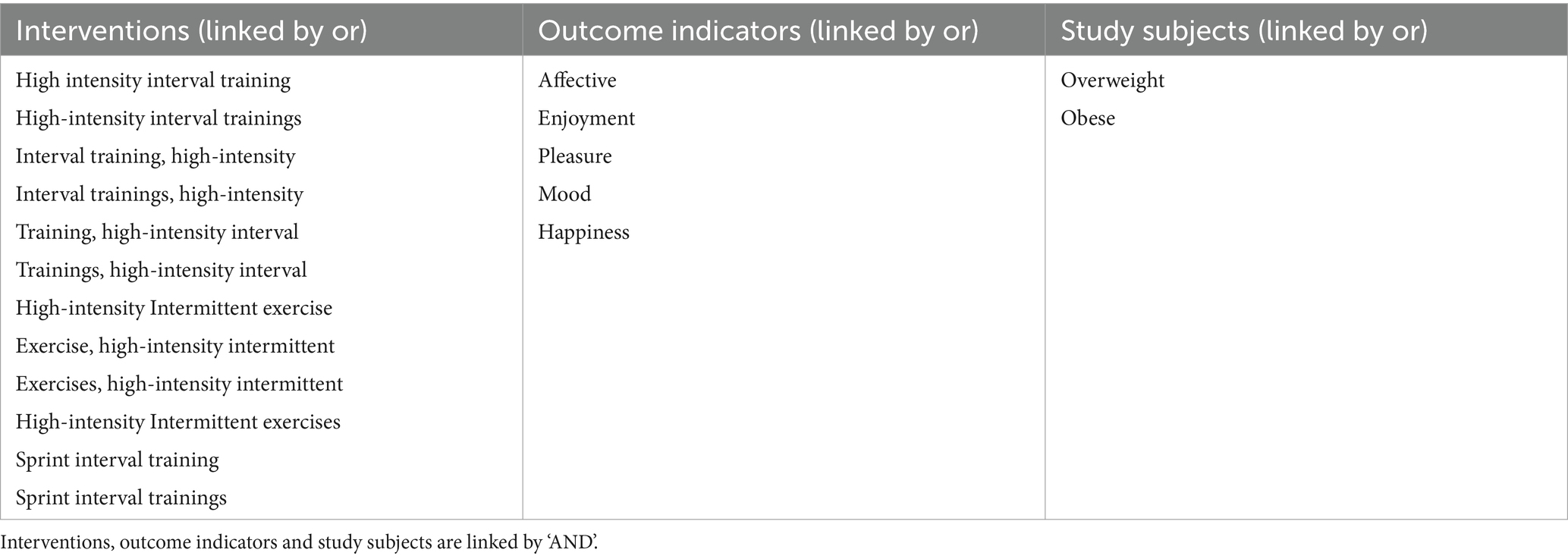

2 Materials and methods 2.1 Literature retrievalThe study was conducted in accordance with the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions and the PRISMA Statement for Systematic Evaluation (27). Four electronic literature databases were searched to identify included studies: Cochrane, EMBASE, PubMed and Web of Science. Search terms included combinations of subject and free words for interventions, outcome indicators, and study subjects (see Table 1).

Table 1. Systematic review search terms.

2.2 Eligibility criteriaThe following inclusion criteria were used to select studies: (1) overweight or obese adults aged ≥18 years; (2) comparison of the HIIT with the MICT; (3) reported measures of affect, pleasure, and intention and (4) overweight or obese who participated in HIIT and MICT. All the studies are randomized controlled trials.

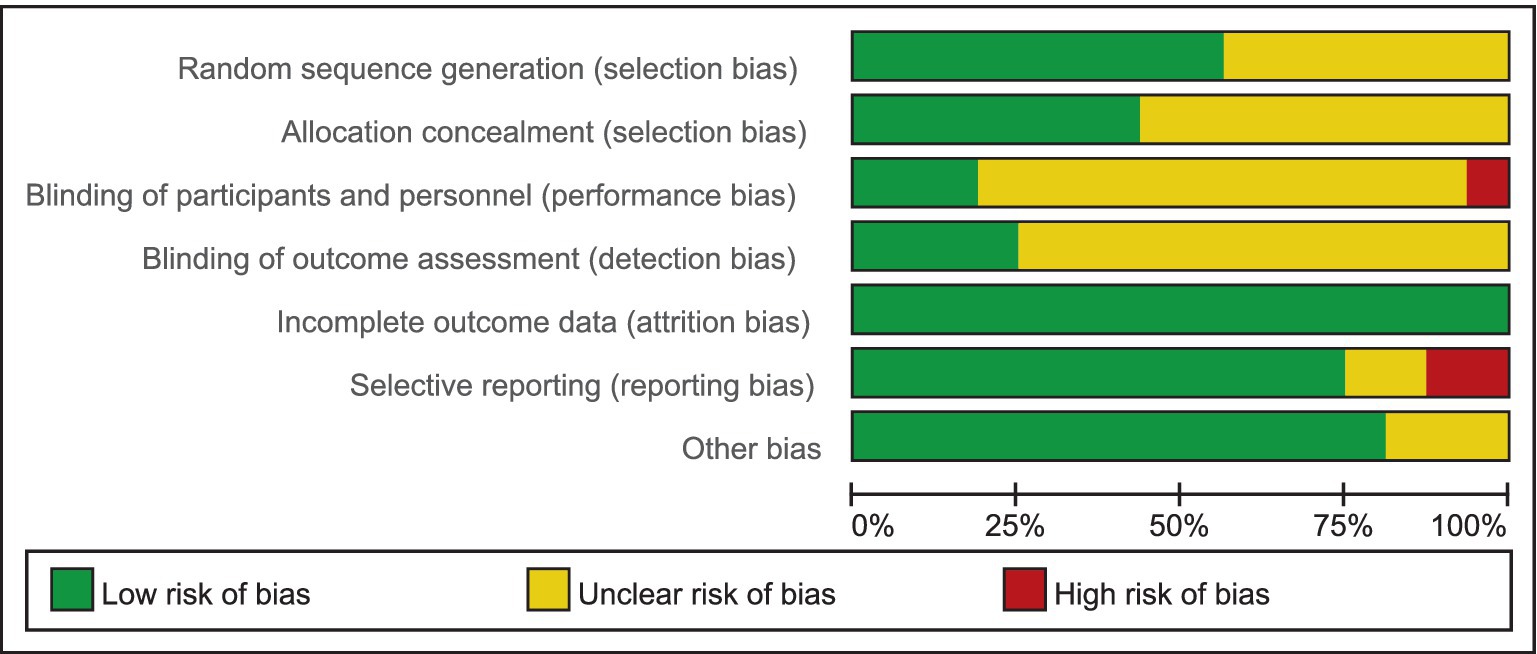

2.3 Literature quality evaluationIn this study, 2 evaluators (YL and JSZ) independently assessed the quality of the included literature by using Cochrane Collaboration’s tool for assessing risk of bias. The quality of the literature was systematically evaluated in the following 7 areas: (1) description of the randomization method; (2) concealment of the allocation scheme; (3) double-blind principle; (4) blinding principle for outcome evaluation; (5) data completeness; (6) selective reporting of outcome results; and (7) assessment of the presence of other biases (Figure 1).

Figure 1. The bias risk assessment included in the literature. Green represents low risk and red represents high risk; yellow represents uncertainty.

2.4 Data extractionData extraction and literature quality assessment were conducted independently by 2 evaluators (YL and JSZ) who extracted data from the included studies into an electronic data extraction form. When there is disagreement, a third reviewer will reevaluate it. Extracted data included literature general study information, study participant information (number, age, BMI), intervention characteristics (intensity, duration), and data on outcome indicators. When situations existed where data were unavailable, but graphical displays were available, we extracted data using a freely available web-based data extraction tool (Engauge Digitizer version 12.1) (28–31).

Data extraction and literature quality assessment were compared between two evaluators, with any disagreements being resolved by a third evaluator.

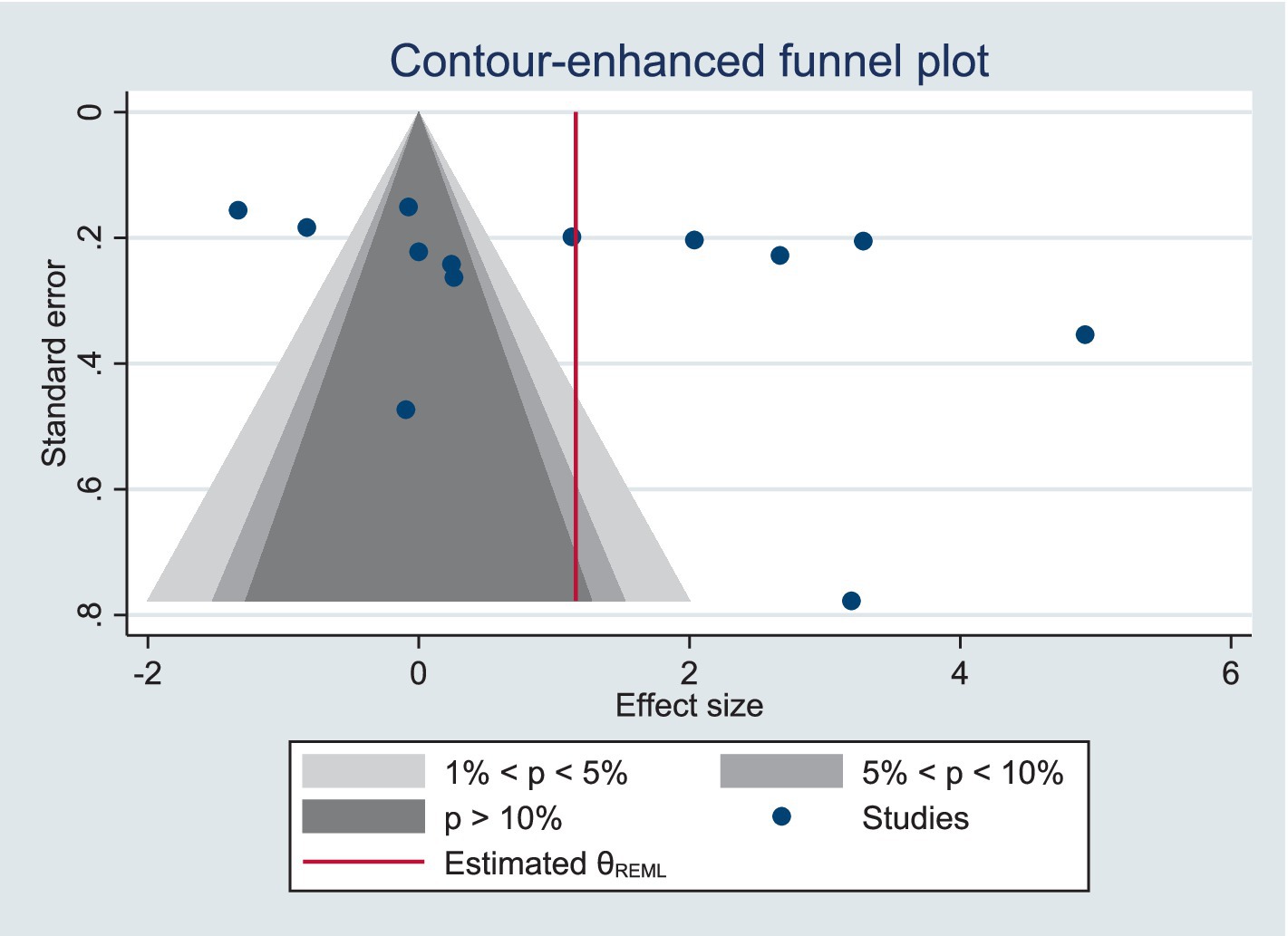

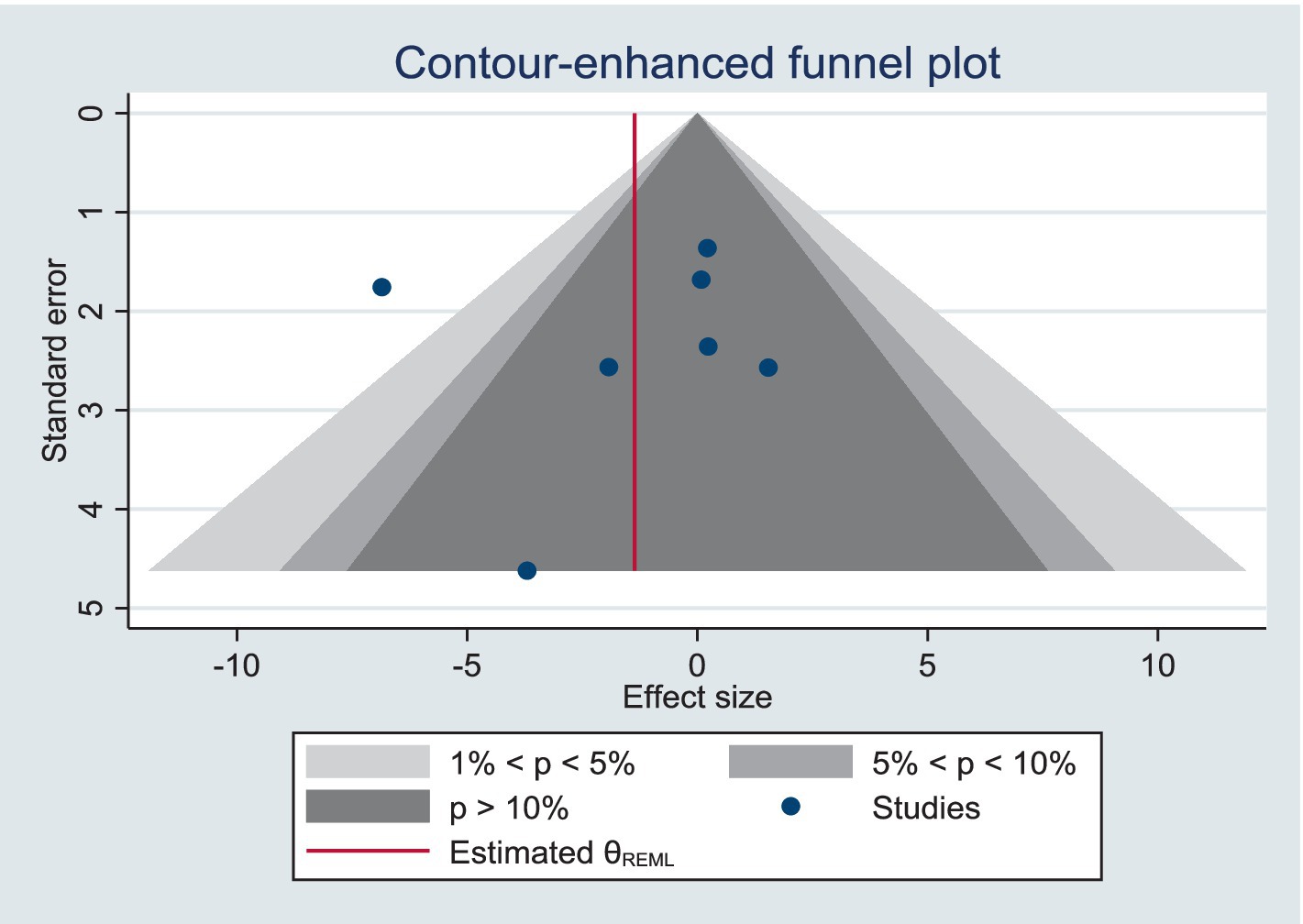

2.5 Publication biasA visual analysis of funnel plot and the Egger’s and Begg’s test were performed to assess the publication bias across studies. At the same time, we used trim-and-fill process to assess the publication bias. This method involves examining the correlation between effect sizes and standard errors of effect sizes to determine if there is a significant association between study effect size and study precision.

2.6 Statistical analysisEffect sizes were determined by calculating the standardized mean difference (SMD). Heterogeneity was tested using I2. I2 for 0–50% is low heterogeneity and 50–100% is high heterogeneity (32). Due to the heterogeneity of the Meta-analysis, a random effects model was chosen to integrate the combined data across the text. Review Manager 5.4.1 was used to perform three statistical analyses with confidence intervals (CI) of 95% for the three outcomes (Physical Activity Enjoyment Scale, Feeling Scale and Felt Arousal Scale) of this study.

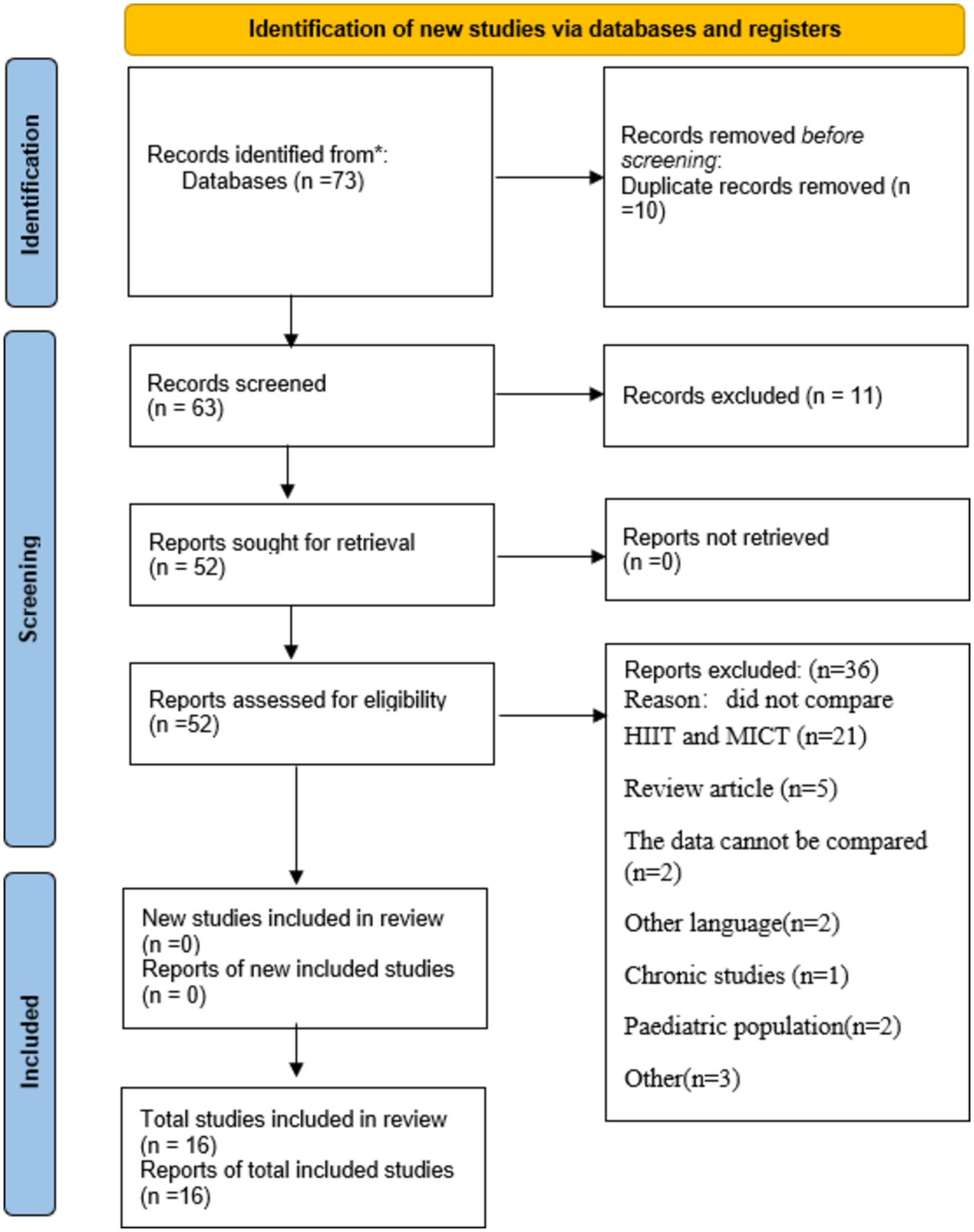

3 Results 3.1 Literature screening resultsThe initial review yielded 73 studies, and after excluding 10 duplicates, 11 studies that were not relevant to the topic, 21 studies that did not compared HIIT and MICT, 5 review studies, 2studies that had the same data and could not be analyzed based on the titles and abstracts, 2 other language studies, 1 chronic study, 2paediatric studies and 3 other studies, there were still 16 studies that needed to be evaluated in full text. Figure 2 illustrates the PRISMA process for study selection.

Figure 2. The flow chart of literature inclusion screening.

A total of 537 participants met the inclusion criteria in 16 studies, including 213 participants in HIIT, 183 participants in MICT, 84 participants in alternating HIIT and MICT, and 57 participants in other forms of intervention (self-selected intensity exercise, very high-intensity interval exercise, repetitive sprint training, and blank control). All participants were between the ages of 18–70 years, had an intervention duration of 1–16 weeks, and had a BMI of 25 or higher. Five studies crossed over two exercises with the same group of participants. Eleven studies had participants under the age of 40 years, three between the ages of 40–60 years, and two over the age of 60 years.

3.2 Quality evaluation included in the studyNine studies described the use of randomized grouping methods, such as the random number table method or computer generated randomization (21, 29, 31, 33–38), they were therefore assessed as having a low risk of bias. Seven studies were assessed as having an unclear risk of bias due to the lack of description of the randomization method (28, 30, 39–43).

Seven studies described a method of allocation concealment in which sealed opaque envelopes were employed or allocated by a third people (31, 33, 36–40), thus were assessed as having a low risk of bias. The remaining 10 studies did not describe the allocation hiding method, thus indicating an unclear risk of bias (21, 28–30, 34, 35, 41–43).

One study showed that participants were not blinded (21), it was therefore assessed as having a high risk of performance bias. Three studies have a low risk of bias due to the description of the double-blind method (34, 40, 43). The rest 12 studies did not describe the use of blinding of participates and personnel (28–31, 33, 35–39, 41, 42), thus indicating an unclear risk of bias.

In four studies, detection bias was judged to be low risk because they provided detailed information on the assessment of blinded outcomes (21, 28, 35, 41). The other 12 studies were judged to have uncertain risk because there was no description of blind outcome assessment (29–31, 33, 34, 36–40, 42, 43).

All 16 studies, reported complete outcome data, thus were assessed as having a low risk of bias.

Two studies did not report all pre-specified primary outcome (30, 34), thus were judged to be high reporting risk. Two studies had insufficient information to determine whether there was a risk of selective reporting of results (39, 41), thus were judged to be unclear reporting risk bias. The other 12 studies were judged to have low risk because all needed outcomes have been reported (21, 28, 29, 31, 33, 35–38, 40, 42, 43).

3.3 Publication bias and sensitivity analysisMeta-analysis showed high heterogeneity of PACES and FS, and exclusion of the studies failed to reduce the level of heterogeneity, indicating a stable overall outcome. However, after excluding two studies (31, 34) the heterogeneity of PACES was significantly reduced to a relatively low level (I2 = 46%). All two studies had an intervention duration of 12 weeks, three times per week, to further investigate the possibility of high heterogeneity, we performed subgroup analyses for age, form of exercise, and duration of exercise, but the significance of the results did not change significantly.

We used funnel plot and trim and fill process to assess publication bias. Based on visual observations, we found that the funnel plot for PACES and FS, there is no significant asymmetry (Figures 3, 4), which suggests that the included studies may not be significantly affected by publication bias, so the results of the meta-analysis may be relatively reliable. Further quantitative tests showed that there was no significant publication bias across studies (Begg’s test, p = 0.100; Egger’s test, p = 0.152, Supplementary Figure 1; The estimated effect size is 1.160 with a 95% confidence interval of 0.147 to 2.173, Supplementary Figure 2. Begg’s test, p = 0.368; Egger’s test, p = 0.867, Supplementary Figure 3; The estimated effect size is −1.362 with a 95% confidence interval of −3.787 to 1.063, Supplementary Figure 4). The analysis revealed no studies to be supplemented, indicating that there was no significant publication bias in the current dataset, or that the effect of publication bias was not large enough to be corrected by trim and fill process.

Figure 3. Funnel plot for PACES meta-analysis.

Figure 4. Funnel plot for FS meta-analysis.

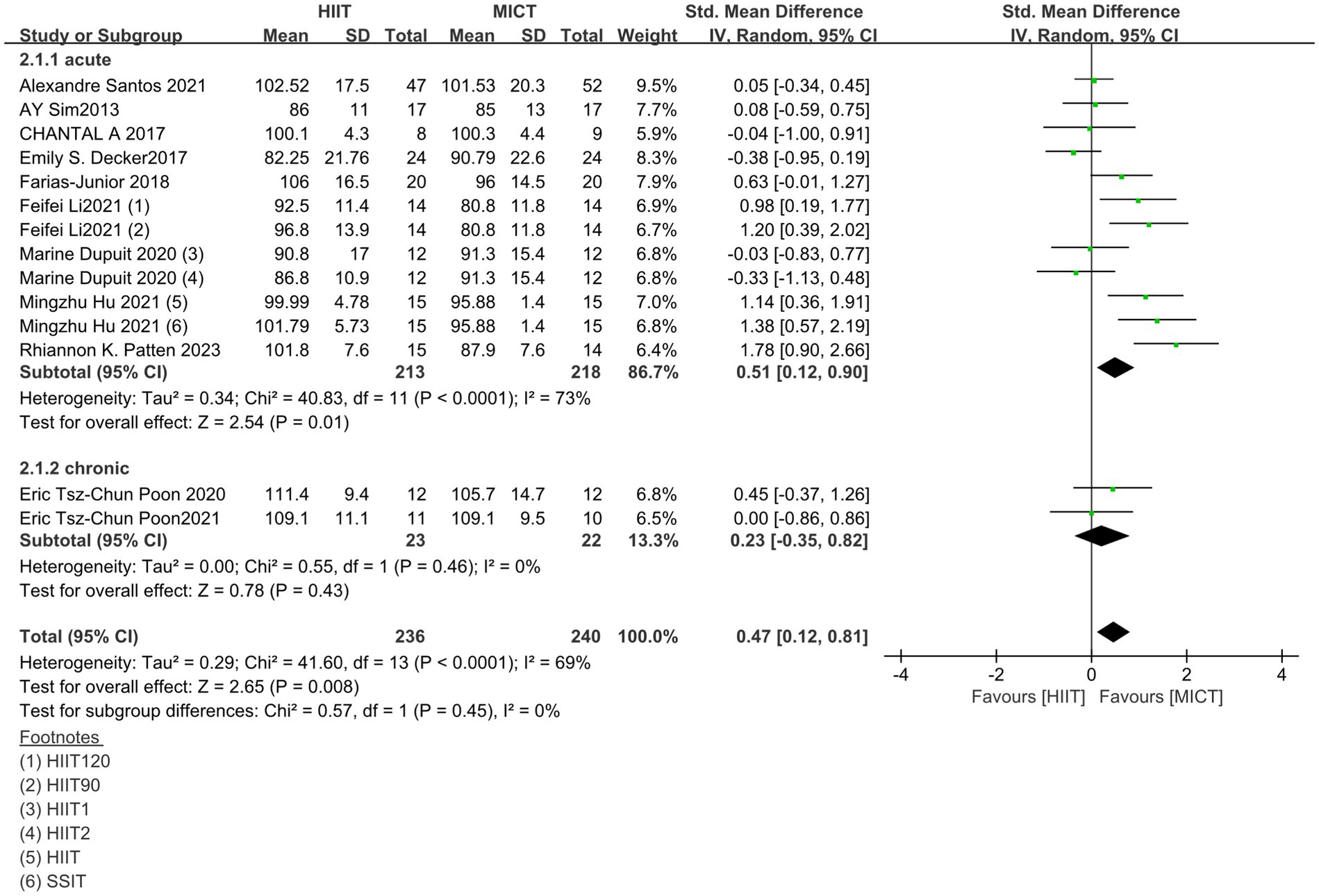

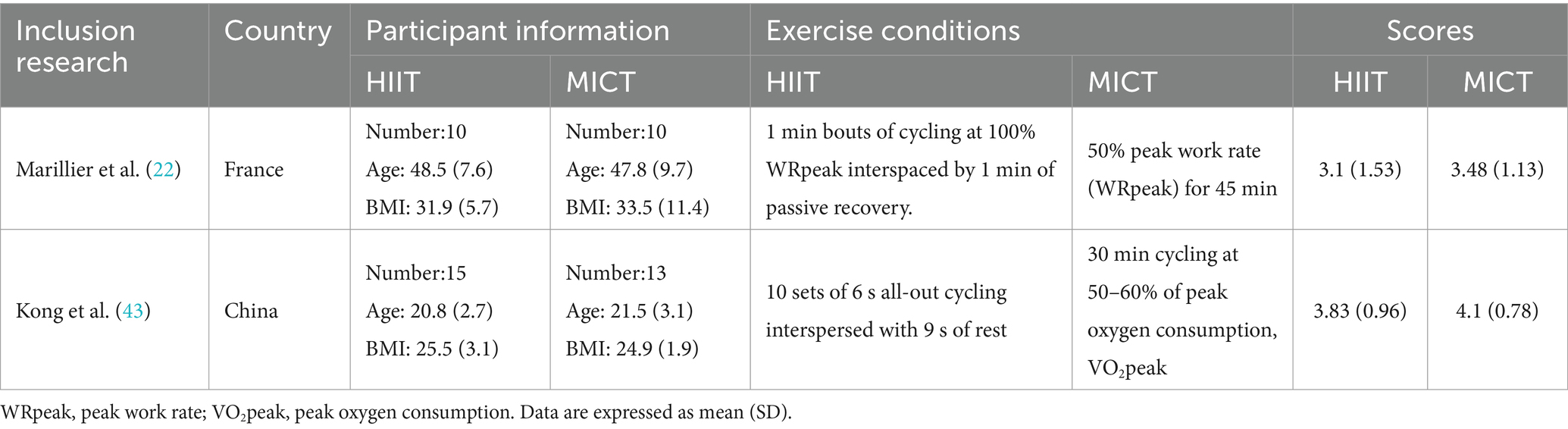

3.4 Meta-analysisStudy characteristics are summarized in Table 2.

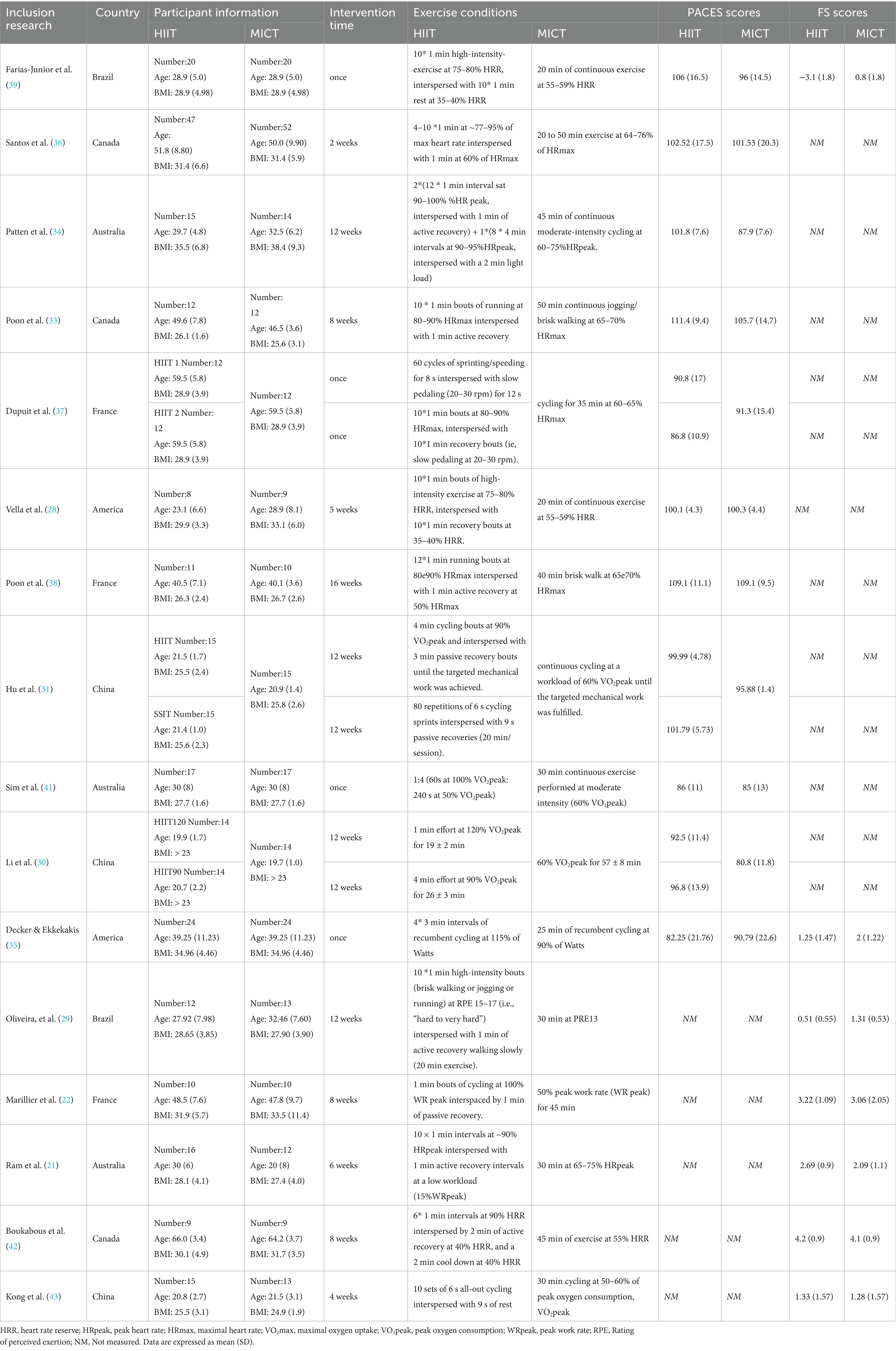

Table 2. Enjoyment and affective data of the selected studies.

3.4.1 Enjoyment response analysisA total of 11 studies have measured the enjoyment response to HIIT and MICT (Table 2) in a manner that was measured using the Physical Activity Enjoyment Scale (PACES; (44)) at the end of training. Two of the studies were measured once after 8 and 16 weeks of training, so these two studies were chronic studies (33, 38) and the rest were acute studies. A high level of heterogeneity was observed in the combined results (I2 = 69%), so a random-effects model was used. Meta-analysis showed that the overall effect of the pleasure response (SMD = 0.47; 95% CI = 0.12 ~ 081; p < 0.05) was statistically significant, indicating that the difference in the rate of outcome events between the two groups was statistically significant (Figure 5).

Figure 5. Standardized mean difference of physical activity enjoyment scale between HIIT and MICT conditions. CI, confidence interval; HIIT, high intensity interval training; MICT, moderate intensity continuous training.

However, it is still difficult to evaluate what the clinical consequences of this heterogeneity may be for future settings. So a prediction interval is reported in the study to illustrate which range of true effects can be expected in future settings. The resulting SDPI = 0.566, 95% prediction interval ranging from −0.758 to 1.688. This suggests that the true effect size in similar future studies may be in this range, or may even be opposite to summary point estimate of the meta-analysis, or have greater effect uncertainty (45).

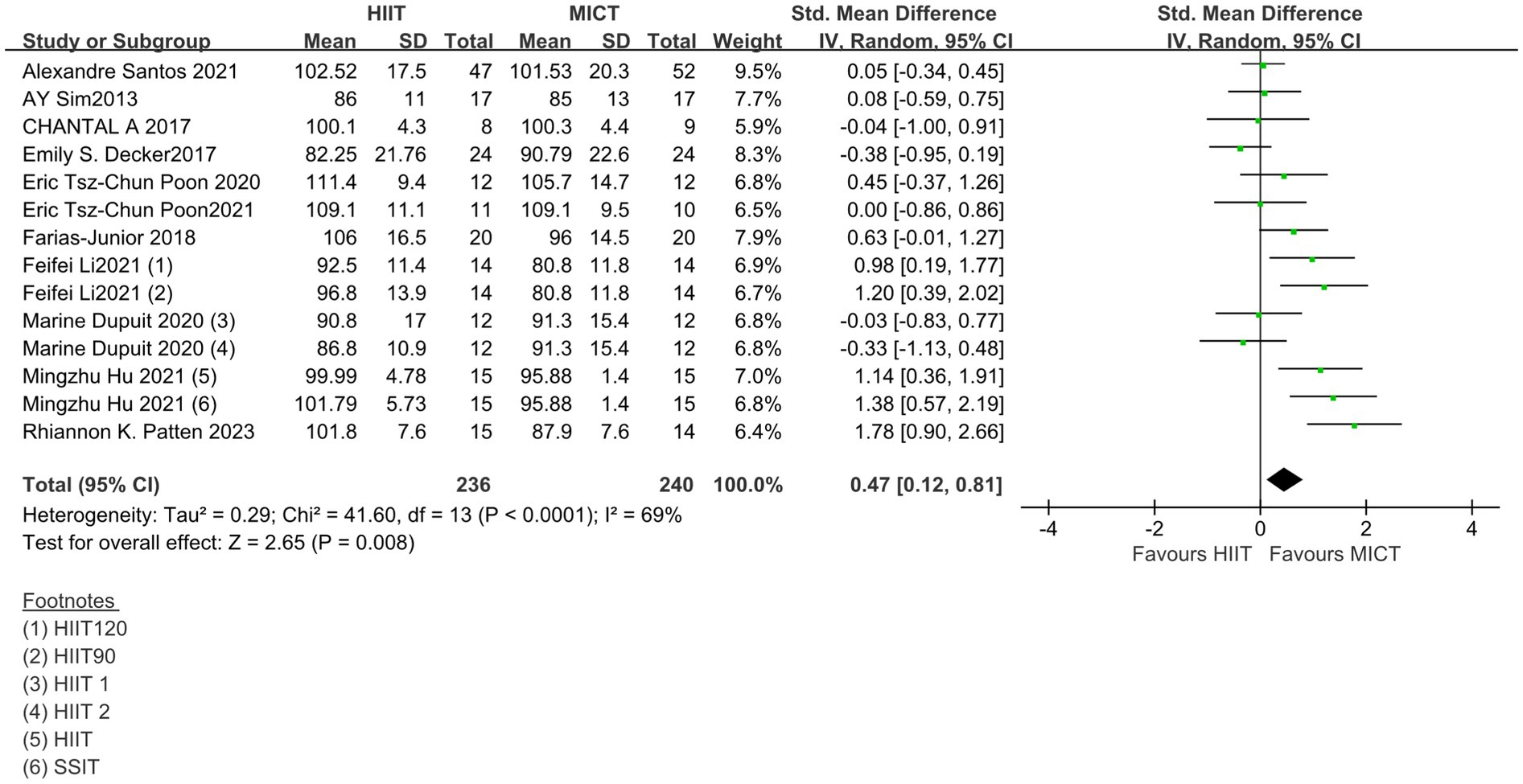

3.4.1.1 Subgroup analysis of acute and chronic studiesA subgroup analysis was performed to investigate the difference between acute and chronic studies. As shown in Figure 6, nine acute studies (SMD = 0.51; 95% CI = 0.12 to 0.90; p < 0.05) showed beneficial overall effects of HIIT on enjoyment, indicating that HIIT exercise may contribute to obtaining psychological responses that are equal to or more positive than MICT sessions in short period. In contrast, two chronic studies (SMD =0.23; 95% CI = −0.35 to 0.82; p > 0.05) did not show a significant effect.

Figure 6. Results of subgroup analysis of acute and chronic studies; CI, confidence interval; HIIT, high intensity interval training; MICT, moderate intensity continuous training.

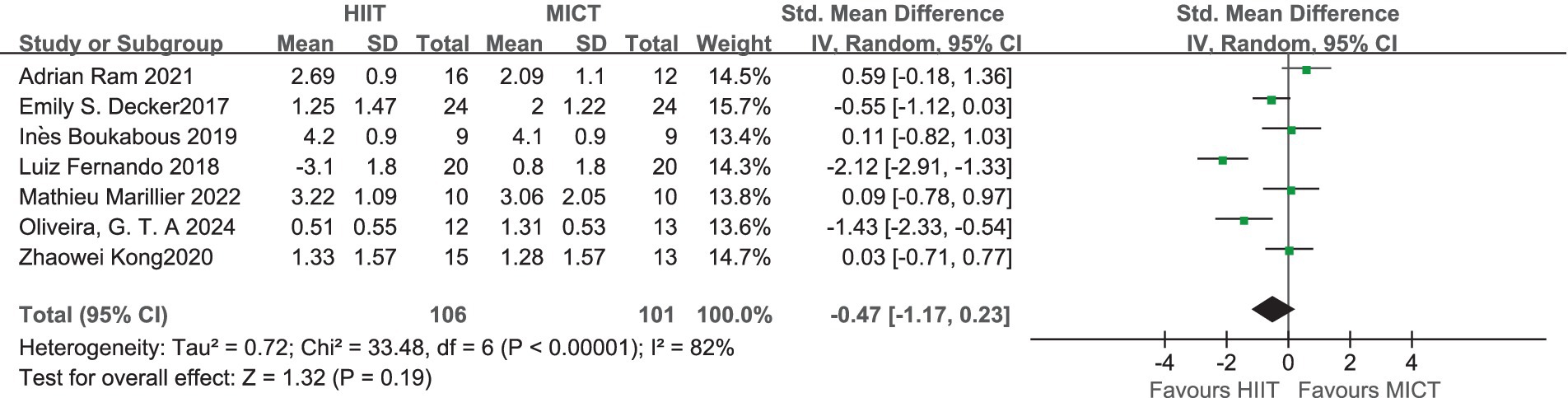

3.4.2 Affective response analysisA total of seven studies have measured affective responses to HIIT and MICT using the Feeling Scale (FS; (46)) before, during and after exercise (Table 3), all of them are acute studies. For studies where multiple measures of affective responses (pre-, mid-, and post-exercise) were present, we calculated mean and standard deviation values, reducing the data for each exercise condition to only one value. A high level of heterogeneity was observed in the combined outcome Feeling Scale (I2 = 82%), so a random-effects model was used. Meta-analysis showed that the overall effect of Feeling Scale (SMD = −0.47; 95% CI = −1.17 ~ 0.23; p > 0.05) was not statistically significant, indicating that the difference in the rates of outcome events between the two groups was not statistically significant (Figure 7). The resulting SDPI = 0.920, 95% prediction interval ranging from −2.721 to 1.781. This suggests that although the current effect estimates are negative, near zero or slightly positive effects may be expected in future studies.

Table 3. Arousal data of the selected studies.

Figure 7. Standardized mean difference of Feeling Scale between HIIT and MICT conditions. CI, confidence interval; HIIT, high intensity interval training; MICT, moderate intensity continuous training.

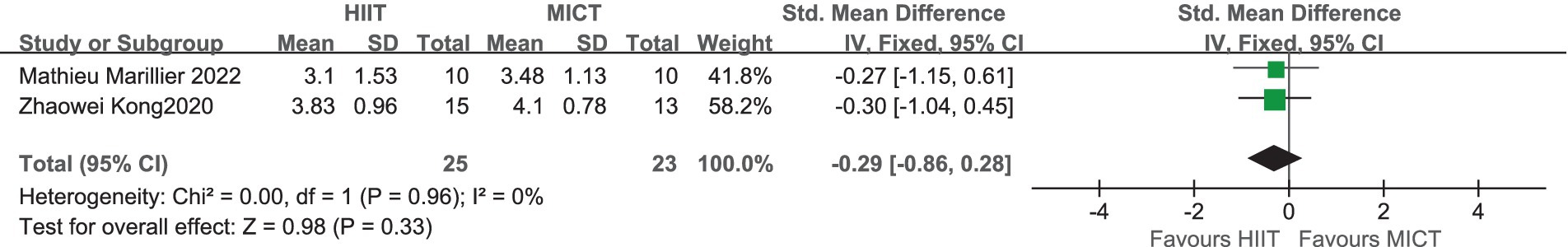

3.4.3 Arousal analysisTwo of these studies also used the Felt Arousal Scale (47) measured before and after exercise (Table 3). A low level of heterogeneity was observed in the combined outcome Felt Arousal Scale (I2 = 0%), and therefore a fixed-effects model was used. Meta-analysis showed that the overall effect of Felt Arousal Scale (SMD = −0.29; 95% CI = −0.86 ~ 0.28; p > 0.05) was not statistically significant, indicating that the difference in the rate of outcome events between the two groups was not statistically significant (Figure 8).

Figure 8. Standardized mean difference of Felt Arousal Scale between HIIT and MICT conditions. CI, confidence interval; HIIT, high intensity interval training; MICT, moderate intensity continuous training.

4 DiscussionThe objective of this meta-analysis is to evaluate and compare the effectiveness of HIIT and MICT on enjoyment and affective responses in overweight or obese people, and to explore the most appropriate exercise mode for overweight or obese people.

4.1 Enjoyment response of HIIT compared with MICTWhile affect is a conscious response to an emotional direction (positive, neutral, or negative), enjoyment is a more specific feeling (48). Traditional concept suggests that high-intensity exercise above the ventilation threshold can cause unpleasant feelings about exercise (49). Although HIIT is a form of high-intensity exercise, it is characterized by brief, repeated intervals of rest or low-intensity exercise (50). There are multiple “recovery” cycles, which can lead to a psychological “rebound effect” in exercisers. Jung suggests that during recovery intervals there may be a “rebound effect” whereby participants may feel a more positive emotional response during the recovery period, as the intervals may contribute to a repeated boost in confidence during a single workout, allowing participants to know that they are approaching a “comfort zone” for recovery, and thus mobilizing their own positive emotions (51), Participants’ confidence and mobilization of positive emotions can thus be continuously enhanced. However, the “rebound effect” seems to occur only on the post-exercise scale, because participants have more time to cushion and recover after exercise, and the use of the scale during exercise may not be a good explanation for this effect, because participants will still feel tired during short intervals of exercise. Therefore, the overall effect of HIIT on the PACES scale measured after exercise will be better than MICT.

In addition, exercise preference is one of the factors that influence people’s choice of different types of exercise. Hedonistic theories of behavior suggest that people are intrinsically predisposed to behaviors that bring them pleasure and stay away from those that bring them displeasure (52). It has been suggested that HIIT may be preferred for achieving personal health goals better than MICT, which may cause participants to become frustrated and give up more easily because it may take more time (53).

It is worth noting that it involves both acute and chronic studies on enjoyment response. The result of subgroup analysis of acute and chronic studies shows that HIIT may contribute to obtaining psychological responses that are equal to or more positive than MICT in short period. The reason why it is feasible to include both acute and chronic is because we are looking at an overall effect. Acute effects may disappear over time, or adaptive changes may occur over a long period of time. By combining acute and chronic studies, we can reveal more complex time-dependent effects. The overall effect shows beneficial effects of HIIT on enjoyment indicating that overweight or obese people may more willing to try HIIT due to hedonistic theories of behavior.

4.2 Affective response of HIIT compared with MICTResults show that the difference in the rates of outcome events between the two groups was not statistically significant. It might because HIIT is performed using multiple sets of stimulus/recovery combinations, and variations in the ratio of stimulus to recovery time will affect the emotional experience of participants, which will likely have an impact on affective responses (43). In the experimental design of Oliveira et al. (29), the affective responses to HIIT were lower than those of MICT in a pattern of 1 min of exercise with 1 min of active recovery as a group (29). However, in the experimental design of Ram et al. the affective responses to HIIT were higher than those of MICT in a pattern of 10 * 1 min intervals at 90% peak heart rate with 1 min active recovery intervals at a low workload (15% WRpeak) (21), suggesting that by rationalizing the ratio of stimulation to recovery time in high-intensity exercise and improving the affective responses resulting from influencing it, it might be a good prescription for the overweight and obese groups.

4.3 Arousal of HIIT compared with MICTTwo studies reported data on the assessment of Arousal during exercise using Felt Arousal Scale (47). Due to the small number of literatures and the different measurement times of FAS scale in the two studies, the average score was calculated for analysis. The results showed that both HIIT and MICT could bring positive emotional activation responses to participants, but there was no significant difference between groups (SMD = −0.29; 95% CI = −0.86 ~ 0.28; p > 0.05). Due to the limited amount of literature, it may not be possible to fully understand the research status and development trend of this field. In addition, the lack of sufficient information may also limit the in-depth discussion of certain specific issues. However, studies have shown that emotional activation depends on the intensity of the activity (e.g., light or moderate intensity) or the different moments of the session (e.g., warm up, cool down) (54). Thus, the results should be treated with caution.

In conclusion, this review showed that HIIT can bring better pleasure response than MICT in overweight or obese people, but there is no significant difference in emotional response. It is possible that the inconsistency between this conclusion and the results of existing studies may also be due to differences in the interventions, such as the relative intensity, duration, and total number of work sessions completed (34, 39); and heterogeneity in the backgrounds of the participants, such as age, activity level, and obesity (29, 35, 42). Since the study population of the present meta-analysis was exclusively obese and overweight patients, whereas previous meta-analyses have had a much broader study population (22, 23), BMI may be one of the factors influencing the discrepancy between the results of the present study and those of previous studies. It has been shown that obese women experience lower levels of pleasure and energy compared to non-obese women, which may partially explain their significantly lower levels of participation in physical activity (55), and therefore this may make a smaller difference in the emotional responses of the obese group to the two types of exercise.

5 LimitationsRegarding the risk of bias, the FS and PACES analyses showed heterogeneity of the data, a fact that should be considered in the interpretation of the present study. The following reasons for the significant level of heterogeneity in this study may exist: first, the diversity of exercise styles. Different training methods may have different effects on pleasurable and affective responses, leading to instability in the results (e.g., different stimulus to recovery ratios). Second, we must recognize the inherent limitations associated with Meta-analysis. For example, the possibility of publication bias cannot be completely ruled out, i.e., studies with significant results are more likely to be published, which may bias our results. Third, due to limitations in the available literature, we may not have access to all relevant data, which may affect our statistical analysis. Fourth, there may have been inappropriate controls or unconsidered variables in the studies, further contributing to heterogeneity. Although our main results attempted to reduce heterogeneity to a large extent, heterogeneity was not completely eliminated. Therefore, future studies may consider focusing on a particular type with a better study design to cope with the problem when more relevant studies become available. Fifth, some literature data only provided figures without specific values, so Engauge Digitizer was used to estimate and extract the data, which may have some differences with the original data and may lead to inaccurate analysis results.

6 ConclusionWe conducted a meta-analysis to compare which exercise modality, HIIT or MICT, brings better enjoyment and affective responses in overweight or obese individuals. We found that HIIT caused participants to experience higher enjoyment and similar affect responses compared to MICT, implying that time-efficient training modalities such as HIIT seem to have a place in the choice of exercise prescription for overweight and obese individuals. We therefore conclude that HIIT exercise may be a viable strategy for improving health.

Data availability statementThe original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributionsYL: Conceptualization, Data curation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. JZ: Conceptualization, Supervision, Writing – review & editing. HJ: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing – review & editing. XM: Conceptualization, Supervision, Writing – review & editing. JH: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Methodology, Writing – review & editing.

FundingThe author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. This research was supported by the National Social Science Fund of China (project 22XTY008).

Conflict of interestThe authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s noteAll claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary materialThe Supplementary material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpubh.2024.1487789/full#supplementary-material

References2. Wu, W, Chen, Z, Han, J, Qian, L, Wang, W, Lei, J, et al. Endocrine, genetic, and microbiome nexus of obesity and potential role of postbiotics: a narrative review. Eat Weight Disord. (2023) 28:84. doi: 10.1007/s40519-023-01593-w

Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

4. Zhang, L, Wang, P, Huang, J, Xing, Y, Wong, FS, Suo, J, et al. Gut microbiota and therapy for obesity and type 2 diabetes. Front Endocrinol. (2024) 15:1333778. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2024.1333778

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

5. Musa, AM, Cortese, S, and Bloodworth, O. The association between obesity and depression in adults: a meta-review. BJPsych Open. (2021) 7:S267. doi: 10.1192/bjo.2021.712

Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

6. De Wit, L, Luppino, F, Van Straten, A, Penninx, B, Zitman, F, and Cuijpers, P. Depression and obesity: a meta-analysis of community-based studies. Psychiatry Res. (2010) 178:230–5. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2009.04.015

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

9. Jakicic, JM, Rogers, RJ, Davis, KK, and Collins, KA. Role of physical activity and exercise in treating patients with overweight and obesity. Clin Chem. (2018) 64:99–107. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2017.272443

Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

10. Rhodes, RE, and Kates, A. Can the affective response to exercise predict future motives and physical activity behavior? A systematic review of published evidence. Ann Behav Med. (2015) 49:715–31. doi: 10.1007/s12160-015-9704-5

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

11. Teixeira, DS, Bastos, V, Andrade, AJ, Palmeira, AL, and Ekkekakis, P. Individualized pleasure-oriented exercise sessions, exercise frequency, and affective outcomes: a pragmatic randomized controlled trial. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. (2024) 21:85. doi: 10.1186/s12966-024-01636-0

Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

13. Gao, H, Li, X, Wei, H, Shao, X, Tan, Z, Lv, S, et al. Efficacy of Baduanjin for obesity and overweight: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Endocrinol. (2024) 15:1338094. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2024.1338094

Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

14. Thedinga, HK, Zehl, R, and Thiel, A. Weight stigma experiences and self-exclusion from sport and exercise settings among people with obesity. BMC Public Health. (2021) 21:565–18. doi: 10.1186/s12889-021-10565-7

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

15. Yin, M, Chen, Z, Nassis, GP, Liu, H, Li, H, Deng, J, et al. Chronic high-intensity interval training and moderate-intensity continuous training are both effective in increasing maximum fat oxidation during exercise in overweight and obese adults: a meta-analysis. J Exerc Sci Fit. (2023) 21:354–65. doi: 10.1016/j.jesf.2023.08.001

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

16. Sanca-Valeriano, S, Espinola-Sánchez, M, Caballero-Alvarado, J, and Canelo-Aybar, C. Effect of high-intensity interval training compared to moderate-intensity continuous training on body composition and insulin sensitivity in overweight and obese adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Heliyon. (2023) 9:e20402. doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2023.e20402

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

17. Song, X, Cui, X, Su, W, Shang, X, Tao, M, Wang, J, et al. Comparative effects of high-intensity interval training and moderate-intensity continuous training on weight and metabolic health in college students with obesity. Sci Rep. (2024) 14:16558. doi: 10.1038/s41598-024-67331-z

Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

18. Wewege, M, Van Den Berg, R, Ward, R, and Keech, A. The effects of high-intensity interval training vs. moderate-intensity continuous training on body composition in overweight and obese adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Obes Rev. (2017) 18:635–46. doi: 10.1111/obr.12532

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

19. Yin, M, Li, H, Bai, M, Liu, H, Chen, Z, Deng, J, et al. Is low-volume high-intensity interval training a time-efficient strategy to improve cardiometabolic health and body composition? A meta-analysis. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab. (2023) 49:273–92. doi: 10.1139/apnm-2023-0329

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

20. Chin, EC, Yu, AP, Lai, CW, Fong, DY, Chan, DK, Wong, SH, et al. Low-frequency HIIT improves body composition and aerobic capacity in overweight men. Med Sci Sports Exerc. (2020) 52:56–66. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0000000000002097

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

21. Ram, A, Marcos, L, Morey, R, Clark, T, Hakansson, S, Ristov, M, et al. Exercise for affect and enjoyment in overweight or obese males: a comparison of high-intensity interval training and moderate-intensity continuous training. Psychol Health Med. (2022) 27:1154–67. doi: 10.1080/13548506.2021.1903055

留言 (0)