Exclusive breastfeeding for the first 6 months of life is the preventive intervention with the greatest potential to reduce child mortality (1). Optimal breastfeeding practices also include initiation within the first hour of life and continuing to breastfeed for up to 2 years or longer as desired by the mother and infant, in addition to introducing complementary foods at around 6 months of age. Breastfeeding is protective against respiratory infections (2, 3), gastrointestinal infections and diarrhea (2, 3), acute otitis media (3–5), sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS) (3, 6, 7), and necrotizing enterocolitis (NEC) in preterm infants (8). It may be associated with a decrease in the infant’s risk for other health conditions (9). In addition, it is also associated with a lower risk of developing breast cancer (3, 10), ovarian, and endometrial cancer (3, 10–12), and cardiovascular disease (13) for the lactating mother, in addition to protection against other diseases, such as type 2 diabetes (3, 14–16). Therefore, breastfeeding is a unique health behavior that substantially benefits both parent and infant. However, despite those well-documented numerous benefits, the World Health Organization (WHO) estimates that only 44% of all infants worldwide are exclusively breastfed for the first 6 months of life (17). Research into the barriers to meeting this goal of exclusive breastfeeding underlines the importance of sociodemographic factors, according to a recent meta-review (18), which found evidence for adverse effects of young maternal age, a low level of education, having to return to work within 12 weeks postpartum, having birthed via cesarean section, and inadequate milk supply. Maternal personality traits, another possible factor affecting infant feeding outcomes, have received little attention from researchers. This mini-review explores this under-researched topic and investigates the possible impact of maternal personality traits on infant feeding outcomes.

Personality traits are enduring patterns of thoughts, feelings, and behaviors that show stability and change over time (19). They tend to change toward greater maturity over the lifespan, with important interpersonal differences in the timing and direction of those changes (20). However, the stability of personality traits is debated, with some researchers arguing that stability depends on environmental factors and measurement methods (21). Personality traits differ from other constructs like mood, which are more transient and contribute to variance in affective measures (22).

The Big Five model, encompassing Openness, Conscientiousness, Extraversion, Agreeableness, and Neuroticism (Emotional Stability), is based on language descriptors and defines human personality at the broadest level (23, 24). Openness to Experience is characterized by traits such as imagination, curiosity, and creativity, contrasted with shallowness and imperceptiveness. Conscientiousness involves traits such as organization, thoroughness, and reliability versus carelessness, negligence, and unreliability. Extraversion encompasses traits such as talkativeness, assertiveness, and high activity levels, as opposed to silence, passivity, and reserve. Agreeableness contrasts traits like kindness, trust, and warmth with hostility, selfishness, and distrust. Lastly, Emotional Stability includes traits like nervousness, moodiness, and temperamentality, as opposed to calmness, self-confidence, and emotional consistency (24). The model was chosen due to its comprehensive framework, and it has been extensively validated across different cultures and populations, making it a robust tool for psychological research (25) which is particularly useful in research areas such as health behaviors, where various personality dimensions can influence outcomes differently (26). For instance, Conscientiousness has been linked to health-promoting behaviors (27), while Neuroticism often correlates with negative health outcomes (28). Conscientiousness is often linked to health-promoting behaviors through mechanisms like self-discipline and goal-directed behavior. Neuroticism, on the other hand, might be associated with negative outcomes due to emotional instability, which can increase stress and hinder adaptive coping strategies. Extraversion may facilitate better social support networks, while Openness is associated with a greater willingness to engage in novel and exploratory behaviors. Finally, Agreeableness could promote positive social interactions, leading to healthier behaviors through cooperation and conflict avoidance.

Its broad applicability makes the model a good choice in examining health behaviors like breastfeeding, which multiple personality dimensions can simultaneously influence. In contrast, specific traits like negative affectivity or trait anxiety, while important, offer a narrower focus and might not capture the full range of personality influences on breastfeeding outcomes.

2 MethodsFrom July 10 to July 12, 2024, the following databases were searched: the Web of Science Core Collection, PubMed, and ProQuest Psychology (which includes APA PsycArticles. APA PsycInfo, APA PsycTests®, Psychology Database, and PTSDpubs). The search expression used was (“maternal personality” OR “maternal psychology” OR “maternal temperament” OR “parental personality” OR “parental psychology” OR “parental temperament” OR “mother’s personality” OR “mother’s psychology” OR “mother’s temperament” OR “parent’s personality” OR “parent’s psychology” OR “parent’s temperament” OR “personality traits” OR “Big Five”) AND (“breastfeeding initiation” OR “exclusive breastfeeding” OR “breastfeeding duration” OR “breastfeeding outcome” OR “breastfeeding behavior” OR “breastfeeding success” OR “breastfeeding practices” OR “lactation initiation” OR “lactation duration” OR “lactation outcome” OR “lactation success” OR “lactation practices” OR “lactation behavior”). This yielded 26 results in the Web of Science, 1802 in PubMed, and 128 in ProQuest Psychology. After analyzing the abstract and, if needed, the body of the article, 10 results from the Web of Science, 12 from PubMed, and five results from ProQuest Psychology met the criteria for inclusion (i.e., they analyzed the associations between maternal personality traits and breastfeeding outcomes). Since “Clinical Lactation,” another professional research journal in the field, is not included in PubMed, a separate search using the same search expression was conducted on July 12, 2024; no additional articles were found. After checking for duplicates, 13 studies remained. However, one study used the Lüscher Color Test as a personality trait measure. It is included in a published list of discredited procedures in psychology (63), and therefore, the study was not included in this mini-review. Two further studies that used the same data set for analysis employed a fundamentally flawed methodology: the sample consisted only of mothers who had exclusively breastfed, eliminating any variability in breastfeeding status. This lack of variation precludes any meaningful analysis of factors influencing the choice to breastfeed exclusively, as all participants have already made the same decision, thereby violating a basic principle of research design, which requires variability in the dependent variable for analysis. In addition, the scale used as the dependent variable is mischaracterized because instead of measuring actual breastfeeding outcomes or behaviors, it comprises subjective items that do not reflect exclusive breastfeeding practices. This misalignment between the intended measurement and the actual construct assessed further invalidates the findings (29). Finally, the studies used data on breastfeeding intentions and personality traits collected retrospectively, 6 to 12 months postpartum, introducing significant recall bias and confounding factors, as the mothers’ breastfeeding decisions and experiences have already been made and could influence their responses. These design flaws led to excluding the two studies from this mini-review.

An additional search of the references in all of the included studies resulted in one more article that was included (30), resulting in a total of 11 studies.

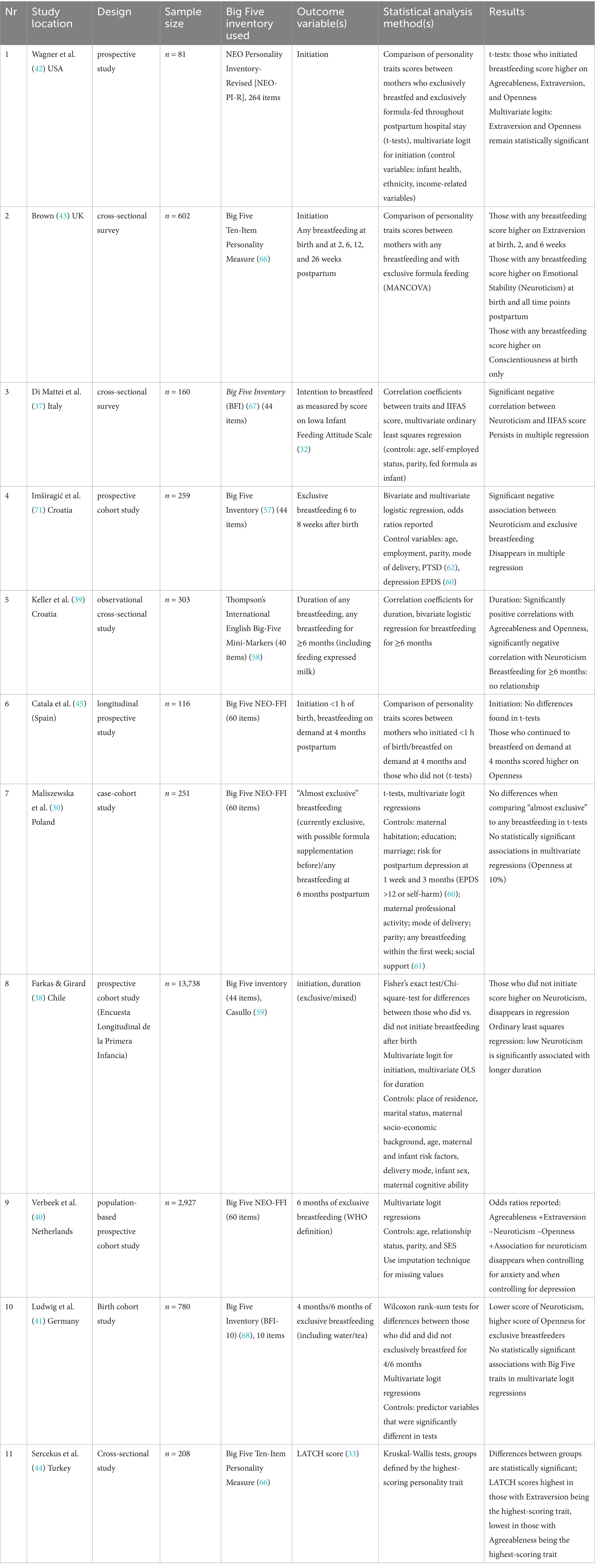

3 ResultsThe 11 studies were conducted in Chile, Croatia (two), Germany, Italy, the Netherlands, Poland, Spain, Türkiye, the United Kingdom, and the United States. All can be classified as primary, observational research in epidemiology (31). Table 1 provides an overview and summary.

Table 1. Overview of the studies included in this mini-review.

Regarding breastfeeding outcomes, attitudes toward breastfeeding (measured using the Iowa Infant Feeding Attitudes Scale (IIFAS), (32)), breastfeeding quality measured using the LATCH score [a tool to assess the quality of the infant’s latch or attachment to the breast, (33)], breastfeeding duration, and any/exclusive/on-demand breastfeeding at certain ages (such as 4 or 6 months postpartum) were used; some studies also included expressing milk using a pump as breastfeeding. The study on attitudes was included because research using the Theory of Planned Behavior (34) approach has suggested that infant feeding decisions are often made during pregnancy (35, 64), with attitudes and knowledge about breastfeeding influencing both decisions and feeding outcomes [see, for example, Lawton et al. (69), Naja et al. (70)] (36).

In addition, the research methodology and statistical analysis methods used differed widely, from cross-sectional to retrospective and prospective (population) cohort studies for the methodology and classical hypothesis testing or bivariate/multivariate regression used for the statistical analysis. Lastly, the resulting sample sizes also varied greatly, ranging from n = 87 in an early study to n = 13,738 in a population-based cohort study. Therefore, the following section offers a narrative synthesis of the results by personality traits and in chronological order of outcomes through pregnancy, the postpartum hospital stay, and the first months of life of the infant. More detailed information on the included studies, including methodology, is provided in Table 1.

Regarding Big Five Neuroticism, the following studies reported statistically significant associations with breastfeeding intentions and outcomes. Di Mattei et al. (37) found a negative correlation between Neuroticism and attitudes toward breastfeeding, as measured by IIFAS scores during pregnancy. Several studies report negative bivariate correlations between Neuroticism and breastfeeding outcomes that disappear in multivariate analysis: Farkas and Gisrard (38) report that those who did not initiate breastfeeding after birth score higher on Neuroticism, but the association disappears in multivariate regressions. Similarly, Srkalović Imširagić et al. (71) report a negative association between Neuroticism and exclusive breastfeeding at 6 to 8 weeks postpartum that disappears in multivariate regressions. For any breastfeeding ≥6 months, Keller et al. (39) report a significant negative correlation with Neuroticism that disappears in multivariate regression, and Verbeek et al. (40) report a negative association between Neuroticism and reaching the WHO’s 6-month exclusive breastfeeding recommendation. Still, this effect disappears when controlling for depression and anxiety. Similarly, Ludwig et al. (41) found a significant negative association between neuroticism and reaching the WHO goal, which disappeared in multivariate regression. Lastly, Farkas and Girard (38) report that lower Neuroticism (higher emotional stability) is associated with longer breastfeeding duration.

For Big Five Extraversion, both Wagner et al. (42) and Brown (43) report a statistically significant correlation between Extraversion and breastfeeding initiation, and Sercekus et al. (44) found significantly higher LATCH scores for mothers who score highest on the Extraversion trait. Brown (43) also reported that those who reported any breastfeeding at birth, 2, and 6 weeks postpartum scored higher on Extraversion than those who stopped breastfeeding. However, Verbeek et al. (40) found a significant negative association between the trait and meeting the WHO’s 6-month exclusive breastfeeding recommendation, while Ludwig et al. (41) as well as Maliszewska et al. (30) reported no significant association.

Concerning Big Five Openness, Wagner et al. (42) also reported a statistically significant positive correlation between the trait and breastfeeding initiation. Catala et al. (45) reported higher Openness scores for those continuing breastfeeding on demand at 4 months postpartum. Keller et al. (39) found a significant positive correlation between Openness and duration of any breastfeeding ≥6 months in bivariate regressions, and Verbeek et al. (40) reported a positive association between Openness and 6 months of exclusive breastfeeding. However, Ludwig et al. (41) and Maliszewska et al. (30)found no significant association between Openness and the same outcome.

For Big Five agreeableness, Wagner et al. (42) reported a significant positive correlation with initiation, which disappeared when controlling for infant health, ethnicity, and income. Keller et al. (39) found a significant positive correlation with any breastfeeding for ≥6 months, and Verbeek et al. (40) found a significant positive association with meeting the goal of 6 months of exclusive breastfeeding. Again, Ludwig et al. (41) and Maliszewska et al. (30)found no significant association between Agreeableness and the same outcome.

Lastly, for Big Five Conscientiousness, Brown (43) reported significantly higher Conscientiousness scores for those with any breastfeeding at birth but no significant differences at later time points. No other studies reported any significant associations.

4 DiscussionThe 11 studies included in this mini-review present highly divergent results regarding the relationship between Big Five personality traits and breastfeeding outcomes. The studies varied significantly in methodologies, including cross-sectional and cohort studies, using convenience and representative samples. They used different tools to measure breastfeeding outcomes, such as the Iowa Infant Feeding Attitudes Scale (IIFAS), LATCH scores, and breastfeeding duration and exclusivity at various postpartum stages. Consistent patterns were hard to identify. Some studies reported significant correlations between specific personality traits and breastfeeding outcomes in bivariate analyses. Still, these associations often disappeared in multivariate regressions when controlling for other factors, suggesting that Big Five personality traits might not independently predict breastfeeding behaviors. Additionally, the results were mixed when examining the duration and exclusivity of breastfeeding: while some studies reported associations with a certain trait, others found no significant links with the same trait. This variability in findings underscores the complexity of breastfeeding outcomes and their determinants. While personality traits may play a role, their influence is likely moderated by other factors, including other psychological, social, and demographic variables. More studies employing state-of-the-art research design and analysis methods are needed to see whether patterns will emerge. In addition, most of the studies had exclusion criteria that effectively limited participation to low obstetric risk patients, so research on other populations, such as high-risk parents or infants, is needed.

The results suggest contrasts with results on other health behaviors and their correlations with Big Five personality traits: according to a meta-synthesis of results, the associations tend to be stronger for Agreeableness, Conscientiousness, and Neuroticism than for Extraversion or Openness to experience (46). Following the model proposed by De Young (47), which suggests that Big Five traits represent two higher-order factors, stability and plasticity, traits related to stability (Agreeableness, Conscientiousness, and Neuroticism) seem to be more important than those related to plasticity (Extraversion and Openness). In addition, they tend to be strongest for mental health outcomes, followed by health behaviors (such as smoking) and physical health outcomes (46). Pletzer et al. (48) provide a meta-synthesis of the HEXACO personality traits model (which, among other differences, adds a sixth trait, honesty-humility) and correlations with health-promoting behaviors. In contrast to Strickhouser et al. (46), they reported the strongest correlations with Conscientiousness, followed by Extraversion, Openness, Honesty-Humility, and Agreeableness, but none with Emotionality. Both meta-analyses also reported substantial variations in correlation strength between traits and specific health behaviors. While breastfeeding should be considered a preventive health behavior in the sense that it requires sustained efforts and directly affects both maternal and infant health outcomes, as discussed in the introduction, research also suggests that the artificial infant milk industry’s predatory marketing efforts (49) are not sufficiently regulated by government policies (50) and directly undermine breastfeeding through several channels, including false claims that “position formula as close to, equivalent or superior to breast milk despite growing evidence that breast milk and breastfeeding have unique properties that cannot be replicated by artificial formula” (51). More recently, the industry skillfully employs online marketing strategies (52), often in violation of the International Code of Marketing of Breast-milk Substitutes 1981 (53), that may directly affect parents’ feeding choices (54).

Since breastfeeding promotes the health of both parent and child, future research could focus more on facets of personality traits specifically related to prosocial behavior, especially altruism. Candidates might include facets of the Big Five traits (55), such as altruism or sympathy, as facets of Agreeableness, or empathy and sensitivity as facets of Emotionality in the HEXACO model. The honesty-humility trait in the abovementioned HEXACO model might be another candidate since individuals scoring high on the trait are more likely to engage in altruistic behaviors, making it a strong predictor of prosocial actions, in addition to Agreeableness and Emotionality (56).

While the studies reviewed rely on two-sample hypothesis testing, correlations, and single or multiple regression analyses to explore the relationship between maternal personality traits and breastfeeding outcomes, these methods may not fully capture the complexity of the underlying processes since personality traits might affect beliefs about ability to breastfeed, measured by constructs such as breastfeeding self-efficacy (72), which might, in turn, affect breastfeeding outcomes. Such indirect relationships might be better understood through more sophisticated analytical techniques, such as mediation or moderation analyses or structural equation modeling (SEM). Four-way causal mediation analysis (65) could be applied to examine how maternal personality traits influence breastfeeding outcomes, distinguishing between direct effects, mediated effects via constructs such as breastfeeding efficacy, and any interaction effects between personality traits and other constructs. This approach offers a detailed breakdown of potential causal mechanisms, allowing for a better understanding of how these factors collectively shape breastfeeding behaviors. By using these methods, future research could provide a more detailed understanding of how maternal personality traits influence breastfeeding, potentially leading to more targeted and effective interventions.

Author contributionsDB: Writing – original draft, Writing – review and editing.

FundingThe author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interestThe author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s noteAll claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References1. Jones, G, Steketee, RW, Black, RE, Bhutta, ZA, and Morris, SSBellagio Child Survival Study Group. How many child deaths can we prevent this year? Lancet. (2003) 362:65–71. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)13811-1

Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

2. Horta, BL, and Victora, CGWorld Health Organization. Short-term effects of breastfeeding: A systematic review on the benefits of breastfeeding on diarrhoea and pneumonia mortality. Geneva: WHO (2013).

3. Ip, S, Chung, M, Raman, G, Chew, P, Magula, N, DeVine, D, et al. Breastfeeding and maternal and infant health outcomes in developed countries. Evidence report/technology assessment no. 153. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (2007)

4. Bowatte, G, Tham, R, Allen, KJ, Tan, DJ, Lau, MXZ, Dai, X, et al. Breastfeeding and childhood acute otitis media: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Acta Paediatr. (2015) 104:85–95. doi: 10.1111/apa.13151

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

5. Tenenbaum Weiss, Y, Ovnat Tamir, S, Globus, O, and Marom, T. Protective characteristics of human breast milk on early childhood otitis media: a narrative review. Breastfeed Med. (2024) 19:73–80. doi: 10.1089/bfm.2023.0237

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

6. Hauck, FR, Thompson, JM, Tanabe, KO, Moon, RY, and Vennemann, MM. Breastfeeding and reduced risk of sudden infant death syndrome: a meta-analysis. Pediatrics. (2011) 128:103–10. doi: 10.1542/peds.2010-3000

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

7. Thompson, J, Tanabe, K, Moon, RY, Mitchell, EA, McGarvey, C, Tappin, D, et al. Duration of breastfeeding and risk of SIDS: an individual participant data meta-analysis. Pediatrics. (2017) 140:e20171147. doi: 10.1542/peds.2017-1147

Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

8. Quigley, M, Embleton, ND, and McGuire, W. Formula versus donor breast milk for feeding preterm or low birth weight infants. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. (2019) 7:CD002971. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD002971.pub5

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

9. Horta, BL, and Victora, CGWorld Health Organization. Long-term effects of breastfeeding: A systematic review. Geneva: World Health Organization (2013).

10. Chowdhury, R, Sinha, B, Sankar, MJ, Taneja, S, Bhandari, N, Rollins, N, et al. Breastfeeding and maternal health outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Acta Paediatr. (2015) 104:96–113. doi: 10.1111/apa.13102

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

11. Luan, NN, Wu, QJ, Gong, TT, Vogtmann, E, Wang, YL, and Lin, B. Breastfeeding and ovarian cancer risk: a meta-analysis of epidemiologic studies. Am J Clin Nutr. (2013) 98:1020–31. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.113.062794

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

12. Sung, HK, Ma, SH, Choi, JY, Hwang, Y, Ahn, C, Kim, BG, et al. The effect of breastfeeding duration and parity on the risk of epithelial ovarian cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Prev Med Public Health. (2016) 49:349–66. doi: 10.3961/jpmph.16.066

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

13. Tschiderer, L, Seekircher, L, Kunutsor, SK, Peters, SA, O’Keeffe, LM, and Willeit, P. Breastfeeding is associated with a reduced maternal cardiovascular risk: systematic review and meta-analysis involving data from 8 studies and 1,192,700 parous women. J Am Heart Assoc. (2022) 11:e022746. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.121.022746

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

14. Aune, D, Norat, T, Romundstad, P, and Vatten, LJ. Breastfeeding and the maternal risk of type 2 diabetes: a systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis of cohort studies. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis. (2014) 24:107–15. doi: 10.1016/j.numecd.2013.10.028

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

15. Jäger, S, Jacobs, S, Kröger, J, Fritsche, A, Schienkiewitz, A, Rubin, D, et al. Breastfeeding and maternal risk of type 2 diabetes: a prospective study and meta-analysis. Diabetologia. (2014) 57:1355–65. doi: 10.1007/s00125-014-3247-3

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

16. Pinho-Gomes, AC, Morelli, G, Jones, A, and Woodward, M. Association of lactation with maternal risk of type 2 diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Diabetes Obes Metab. (2021) 23:1902–16. doi: 10.1111/dom.14417

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

17. World Health Organization . Infant and young child feeding. Geneva: World Health Organization (2023).

18. Mangrio, E, Persson, K, and Bramhagen, AC. Sociodemographic, physical, mental and social factors in the cessation of breastfeeding before 6 months: a systematic review. Scand J Caring Sci. (2018) 32:451–65. doi: 10.1111/scs.12489

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

19. Hampson, S, and Goldberg, LR. Personality stability and change over time. The wiley encyclopedia of personality and individual differences: models and theories. eds. Bernardo. J. Carducci, Christopher S. Nave, Jeffrey S. Mio, Ronald E. Riggio. John Wiley & Sons, Hoboken: NJ. (2020).

20. Bleidorn, W, Hopwood, CJ, Back, MD, Denissen, JJ, Hennecke, M, Hill, PL, et al. Personality trait stability and change. Perspect Sci. (2021) 2:e6009. doi: 10.5964/ps.6009

Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

21. Ardelt, M. Still stable after all these years? Personality stability theory revisited. Soc Psychol Q. (2000) 63:392–405. doi: 10.2307/2695848

Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

22. Anusic, I, and Schimmack, U. Stability and change of personality traits, self-esteem, and well-being: introducing the meta-analytic stability and change model of retest correlations. J Pers Soc Psychol. (2016) 110:766–81. doi: 10.1037/pspp0000066

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

23. Goldberg, LR. A historical survey of personality scales and inventories In: P McReynolds, editor. Advances in psychological assessment. Palo Alto, CA: Science and Behavior Books (1971). 293–336.

24. Goldberg, LR. The structure of phenotypic personality traits. Am Psychol. (1993) 48:26–34. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.48.1.26

Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

25. McCrae, RR, and Costa, PT Jr. The five-factor theory of personality In: OP John, RW Robins, and LA Pervin, editors. Handbook of personality: Theory and research. 3rd ed. New York: Guilford Press (2008). 159–81.

26. John, OP, Naumann, LP, and Soto, CJ. Paradigm shift to the integrative big five trait taxonomy: history, measurement, and conceptual issues In: OP John, RW Robins, and LA Pervin, editors. Handbook of personality: Theory and research. 3rd ed. New York: Guilford Press (2008). 114–58.

27. Bogg, T, and Roberts, BW. The case for conscientiousness: evidence and implications for a personality trait marker of health and longevity. Ann Behav Med. (2013) 45:278–88. doi: 10.1007/s12160-012-9454-6

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

28. Smith, TW. Personality as risk and resilience in physical health. Curr Dir Psychol Sci. (2006) 15:227–31. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8721.2006.00441.x

Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

29. DeVellis, RF. Scale development: Theory and applications. 4th ed SAGE Publications (2016). California: Thousand Oaks.

30. Maliszewska, KM, Bidzan, M, Świątkowska-Freund, M, and Preis, K. Socio-demographic and psychological determinants of exclusive breastfeeding after six months postpartum—a polish case-cohort study. Ginekol Pol. (2018) 89:153–9. doi: 10.5603/GP.a2018.0026

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

31. Röhrig, B, Du Prel, JB, Wachtlin, D, and Blettner, M. Types of study in medical research: part 3 of a series on evaluation of scientific publications. Dtsch Arztebl Int. (2009) 106:262–8. doi: 10.3238/arztebl.2009.0262

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

32. De la Mora, A, Russell, D, Dungy, C, Losch, M, and Dusdieker, L. The Iowa infant feeding attitude scale: analysis of reliability and validity. J Appl Soc Psychol. (1999) 29:2362–80. doi: 10.1111/j.1559-1816.1999.tb00115.x

Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

33. Jensen, D, Wallace, S, and Kelsay, P. LATCH: a breastfeeding charting system and documentation tool. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs. (1994) 23:27–32. doi: 10.1111/j.1552-6909.1994.tb01847.x

Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

34. Ajzen, I. The theory of planned behavior. Organ Behav Hum Decis Process. (1991) 50:179–211. doi: 10.1016/0749-5978(91)90020-T

Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

35. Shaker, I, Scott, JA, and Reid, M. Infant feeding attitudes of expectant parents: breastfeeding and formula feeding. J Adv Nurs. (2004) 45:260–8. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.2003.02887.x

Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

36. Kornides, M, and Kitsantas, P. Evaluation of breastfeeding promotion, support, and knowledge of benefits on breastfeeding outcomes. J Child Health Care. (2013) 17:264–73. doi: 10.1177/1367493512461460

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

37. Di Mattei, VE, Carnelli, L, Bernardi, M, Jongerius, C, Brombin, C, Cugnata, F, et al. Identification of socio-demographic and psychological factors affecting women’s propensity to breastfeed: an Italian cohort. Front Psychol. (2016) 7:1872. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2016.01872

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

38. Farkas, C, and Girard, LC. Breastfeeding initiation and duration in Chile: understanding the social and health determinants. J Epidemiol Community Health. (2019) 73:637–44. doi: 10.1136/jech-2018-211148

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

39. Keller, N, Medved, V, and Armano, G. The influence of maternal personality and risk factors for impaired mother-infant bonding on breastfeeding duration. Breastfeed Med. (2016) 11:532–7. doi: 10.1089/bfm.2016.0093

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

40. Verbeek, T, Quittner, L, de Cock, P, de Groot, N, Bockting, CL, and Burger, H. Personality traits predict meeting the WHO recommendation of 6 months' breastfeeding: a prospective general population cohort study. Adv Neonatal Care. (2019) 19:118–26. doi: 10.1097/ANC.0000000000000547

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

41. Ludwig, A, Doyle, IM, Löffler, A, Breckenkamp, J, Spallek, J, Razum, O, et al. The impact of psychosocial factors on breastfeeding duration in the BaBi-study. Analysis of a birth cohort study in Germany. Midwifery. (2020) 86:102688. doi: 10.1016/j.midw.2020.102688

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

42. Wagner, CL, Wagner, MT, Ebeling, M, Chatman, KG, Cohen, M, and Hulsey, TC. The role of personality and other factors in a mother’s decision to initiate breastfeeding. J Hum Lact. (2006) 22:16–26. doi: 10.1177/0890334405283624

Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

44. Sercekus, P, Ozan, Y, and Yenal, K. The relationship between breastfeeding success and maternal personality traits. J Nurs Midwifery Sci. (2022) 9:12–21. doi: 10.4103/jnms.jnms_16_21

Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

45. Catala, P, Peñacoba, C, Carmona, J, and Marin, D. Maternal personality and psychosocial variables associated with initiation compared to maintenance of breastfeeding: a study in low obstetric risk women. Breastfeed Med. (2018) 13:680–6. doi: 10.1089/bfm.2018.0034

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

48. Pletzer, JL, Thielmann, I, and Zettler, I. Who is healthier? A meta-analysis of the relations between the HEXACO personality domains and health outcomes. Eur J Personal. (2024) 38:342–64. doi: 10.1177/08902070231174574

Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

49. Rollins, N, Piwoz, E, Baker, P, Kingston, G, Mabaso, KM, McCoy, D, et al. Marketing of commercial milk formula: a system to capture parents, communities, science, and policy. Lancet. (2023) 401:486–502. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(22)01931-6

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

50. Baker, P, Smith, JP, Garde, A, Grummer-Strawn, LM, Wood, B, Sen, G, et al. The political economy of infant and young child feeding: confronting corporate power, overcoming structural barriers, and accelerating progress. Lancet. (2023) 401:503–24. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(22)01933-X

Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

51. World Health Organization . How the marketing of formula milk influences our decisions on infant feeding. Geneva: World Health Organization (2022).

52. Jones, A, Bhaumik, S, Morelli, G, Zhao, J, Hendry, M, Grummer-Strawn, L, et al. Digital marketing o

留言 (0)