Postoperative atrial fibrillation (POAF) is the most common secondary arrhythmia after cardiac procedures (1, 2). However, POAF is not a benign disease because it increases the risk of all-cause mortality, prolongs the length of stay in the critical care unit and hospital, and increases the risk of thrombosis such as stroke (3, 4). Besides, POAF also increase the recurrence of atrial fibrillation in the years after cardiac surgery (1). However, the mechanisms underlying POAF have not been elucidated. It is unclear whether POAF is caused by a causal or a simple association. Several studies have revealed that POAF is associated with pericardial effusion and inflammation, pericardial fat metabolic activity, autonomic neurological modulation, re-entry, ectopic activity in the pulmonary vein area, ion channel modifications, gap junction uncoupling, and atrial structural alterations (5–8). Moreover, POAF also affects cardiac function, which attenuates the progression of heart failure and causes poor prognosis in patients with postoperative coronary or valve disease (9).

In clinical practice, treatment of POAF remains limited. The most frequently used antiarrhythmic medications are amiodarone and β-blockers (10, 11). However, currently, there are no specific guidelines for the treatment of POAF. The angiotensin receptor neprilysin inhibitors (ARNIs) sac/val, which perform well in clinical trials of PARADIGM-HF, are effective and safe medications for treating heart failure (12, 13). Recently, several studies have revealed that ARNI drugs not only affect ventricular remodeling but also potentially act on the control of arrhythmia (14–16). Clinical research has also shown that ARNI drugs can decrease the incidence of atrial arrhythmia or ventricular arrhythmia in patients with heart failure. The combined mechanisms for modulation of the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system (RAAS) and sympathetic nervous system (SNS) may explain the combined effect of this drug. Besides, other medications, such as SGLT2i, were shown to have effect on the control of POAF based on meta-analysis (17). The meta-analysis revealed that Dapagliflozin use was associated with significant reduction in AF risk as compared to placebo in overall population and patients with diabetes, whereas the use of other gliflozins did not significantly reduce AF occurrence. However, there is still no study on evaluation of sac/val for controlling POAF in real world setting. Therefore, in the present study, we assumed that sac/val could prevent POAF and ventricular arrhythmia after cardiac surgery, as POAF has mechanisms similar to atrial fibrillation. Herein, we conducted this retrospectively observational study based on our single-centered real-world data, to compare the clinical effect of sac/val with control group for the prevention and treatment of POAF after cardiac surgery.

Methods Study design and patient enrollmentThis retrospective observational cohort study enrolled patients with cardiac diseases and heart failure at the Affiliated Hospital of Qingdao University. Patients were divided into sac/val and control groups according to whether sac/val was administered for more than 7 days. The medicine used was sac/val tablets (Novartis International AG), with a dosage range of 25–200 mg. This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Affiliated Hospital of Qingdao University (grant No. QYFY WZLL 28659).

Inclusion and exclusion criteriaInclusion criteria: (a) patients who underwent cardiac surgery at the Affiliated Hospital of Qingdao University. (b) Patients with structural cardiac malformations and diastolic cardiac dysfunction presenting with symptomatic heart failure. (c) Patients aged >18 years.

Exclusion criteria: (a) patients with a history of arrhythmia, including atrial fibrillation or ventricular tachycardia. (b) Emergency cardiac surgery. (c) Repeated cardiac surgeries (d) Congenital cardiac disease. (e) Apparent liver and/or kidney dysfunction. (f) Concomitant disease requiring long-term radiotherapy, chemotherapy, or hormone therapy. (g) Poorly controlled hyperthyroidism. (h) Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. (i) Prosthetic ascending aortic graft implantation. (j) Concomitant cardiac tumor.

Data collectionThe observational population included patients who underwent coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG) and/or heart valve replacement or repair surgery. Baseline data, including height, weight, age, sex, blood pressure, heart rate, previous medical history, NYHA class, preoperative medication, preoperative echo, surgical procedure, incidence of POAF and/or ventricular arrhythmia, occurrence time of POAF and/or ventricular arrhythmia, postoperative amiodarone use, and major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE), were systematically collected.

DefinitionsPOAF was defined as newly developed postoperative AF in patients without preoperative arrhythmia. MACE were defined as perioperative cardiac death, myocardial infarction (MI), or stroke. Patients routinely underwent ECG within 7 days after the operation. If cardiac arrhythmia occurred, an additional ECG monitoring was performed.

Statistical methodsSPSS software (version 26.0) was used for statistical analysis. Numerical variables are presented as mean ± standard deviation, while categorical variables are presented as frequency (percentage). The t-test, chi-squared test, and Fisher's exact test were used to calculate differences between the sacubitril/valsartan and control groups. Kaplan–Meier survival analysis was used to calculate the incidence of time-dependent POAF, and log-rank test was used for intergroup comparisons. P < 0.05 (bilateral) is defined as statistically significant.

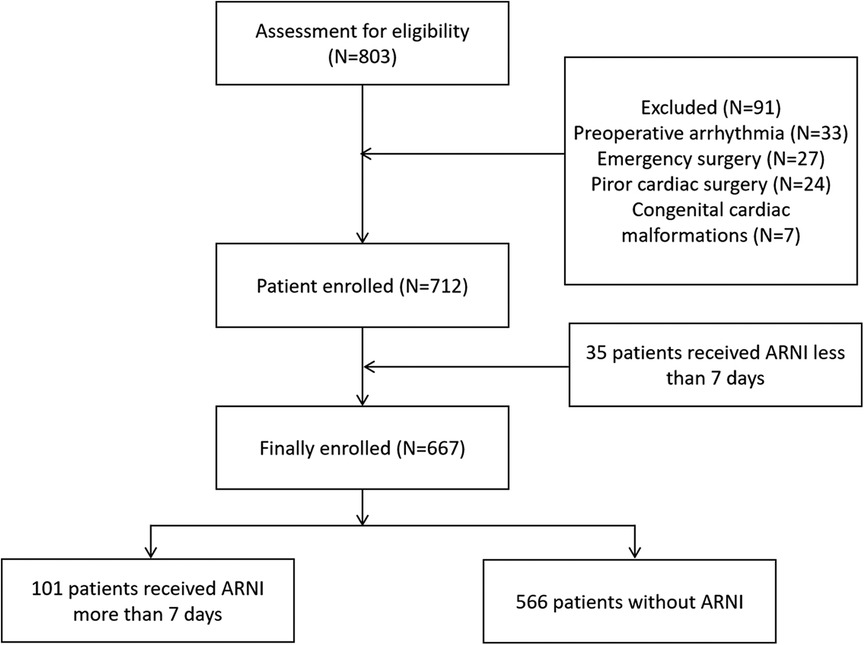

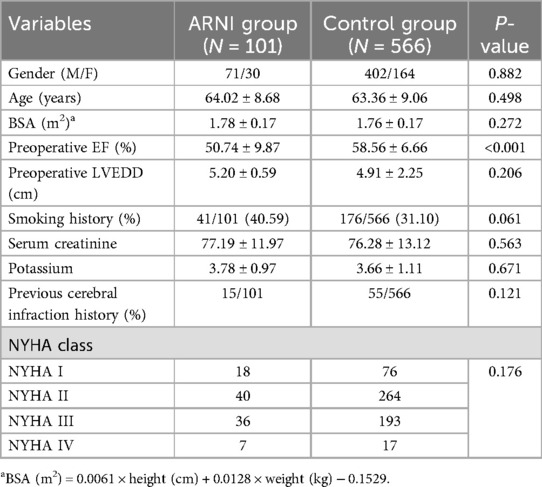

Results Patients’ characteristicsBetween January 2021 and December 2021, 667 eligible adult patients who underwent cardiac surgery at the Affiliated Hospital of Qingdao University were enrolled. The participants were divided into two groups according to whether sac/val was used: the sac/val group (N = 101) and the control group (N = 566). A patient enrollment diagram is shown in Figure 1. The patient characteristics are listed in Table 1. Except for preoperative EF (50.74 ± 9.87 in sac/val group vs. 58.56 ± 6.66 in control group, with P-value <0.05), other baseline and perioperative data was comparable between sac/val group and the control group (all P > 0.05).

Figure 1. Patients’ enrollment diagram.

Table 1. Patients’ baseline characteristics.

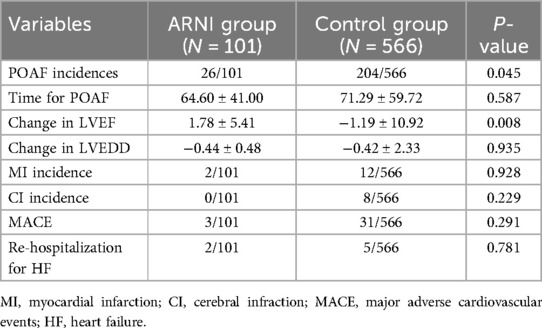

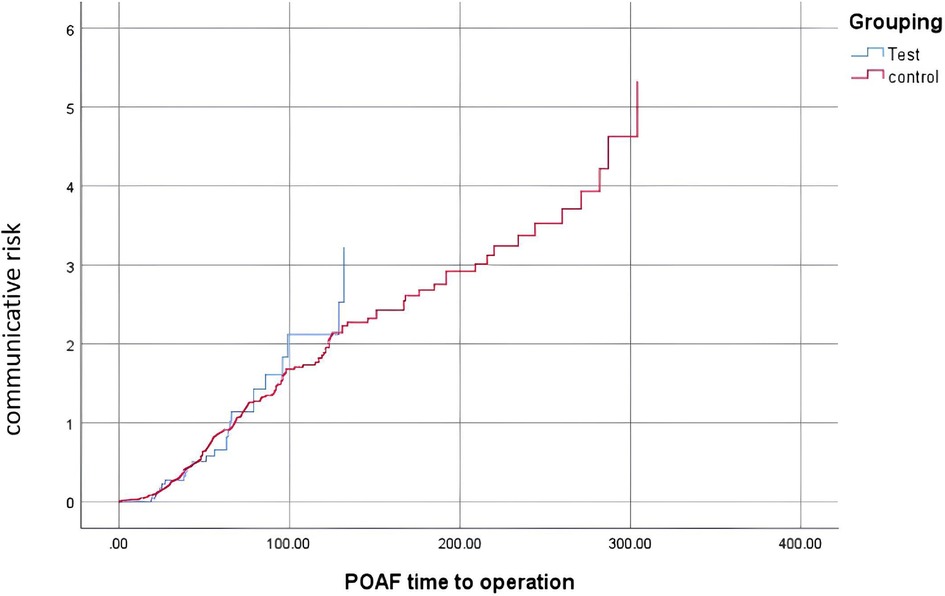

Observational outcomesAs shown in Table 2, the patients in the sac/val group had a lower incidence of POAF than those in the control group (26/101 vs. 204/566, P = 0.045). In addition, as demonstrated in Table 2, patients in the sac/val group showed better left ventricle function recovery, with the dynamic change in LVEF being superior to that of the control group. The change in LVEF in the sac/val group was 1.78 ± 5.41, compared with −1.19 ± 10.92 in the control group (P = 0.008). As demonstrated in Figure 2, patients in the sac/val group showed a similar communicative risk for the concurrence time of POAF using Kaplan–Meier survival analysis compared with the control group.

Table 2. Comparison of patients’ clinical outcomes.

Figure 2. Survival analysis.

DiscussionTo the best of our knowledge, this is the first observational study to evaluate the efficacy and safety of sacubitril/valsartan for the prevention and treatment of POAF after cardiac surgery in adults. The results demonstrated that compared with patients who did not receive sac/valsartan treatment, those who received sacubitril/valsartan treatment showed better POAF control and LVEF recovery.

POAF is the most common arrhythmia after cardiac surgery and is associated with high incidence and poor prognosis (5–9). Preoperative fragility of the atrial base further increased the incidence of POAF (18). However, in clinical practice, surgeons ignore the impact of preoperative medication on the atrial base. Therefore, it is vitally important to optimize the medication strategy of patients with heart disease combined with heart failure to decrease postoperative arrhythmia complications, decrease the length of hospital stay and in-hospital MACE, and improve patients’ survival outcomes.

ARNI drugs act on POAF via several pathways. First, POAF strongly correlated with heart failure. Therefore, POAF triggers rapid and irregular movement of the heart muscles, subsequently alleviating the symptoms of patients with heart failure and promoting the progression of ventricular remodeling. In contrast, severe heart remodeling will further change the atrial base, subsequently affecting electronic signal transformation and improving the alleviation of atrial fibrillation. Therefore, ARNI drugs could both improve the ventricle remodeling, as well as have effect on different kinds of atrial fibrillation (19, 20). Second, the activation of the perioperative sympathetic nervous system (SNS) is involved in the occurrence of POAF. Therefore, ARNI drugs can inhibit enkephalinase to increase the concentration of blood natriuretic peptides (NPs). Therefore, ARNI drugs are involved in the activation of SNS (21). Third, postoperative pericardial effusion and inflammation also affect the occurrence of POAF; a more aggressive intervention indicates more severe inflammation. In several studies, the timing of POAF often overlaps with the peak C-reactive protein (CRP) level, which reflects the role of inflammation in the occurrence and progression of POAF (22). Although this study did not reveal a difference in CRP between the sac/val and control groups because most patients failed to receive regular CRP detection in real-world settings, and a false-positive peak value of CRP was detected in this study.

Overall, in this study, we found that the preoperative sac/val group was associated with a greater decrease in POAF incidence and increased LVEF recovery than the control group. Further pilot experimental studies with larger sample sizes, longer durations, and prospective randomized controlled studies should be conducted to observe the impact of ARNI on POAF in clinical practice.

ConclusionsThis is the first observational study to evaluate the efficacy and safety of sacubitril/valsartan for the prevention and treatment of POAF after cardiac surgery in adults. The results demonstrated that, compared with patients who did not receive sacubitril/valsartan treatment, those who received sacubitril/valsartan treatment showed better POAF control and LVEF recovery. These results should be confirmed by a larger sample size and prospective randomized controlled trials.

Data availability statementThe raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statementThe studies involving humans were approved by The Affiliated Hospital of Qingdao University. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributionsXC: Data curation, Formal Analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Software, Visualization, Writing – original draft. PL: Data curation, Writing – review & editing. FZ: Data curation, Writing – review & editing. DW: Data curation, Writing – review & editing. SY: Conceptualization, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – review & editing. WY: Formal Analysis, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Validation, Writing – review & editing.

FundingThe author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's noteAll claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References1. Gaudino M, Di Franco A, Rong LQ, Piccini J, Mack M. Postoperative atrial fibrillation: from mechanisms to treatment. Eur Heart J. (2023) 44(12):1020–39. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehad019

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

2. Sundaram DM, Vasavada AM, Ravindra C, Rengan V, Meenashi Sundaram P. The management of postoperative atrial fibrillation (POAF): a systematic review. Cureus. (2023) 15(8):e42880. doi: 10.7759/cureus.42880

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

3. Suero OR, Ali AK, Barron LR, Segar MW, Moon MR, Chatterjee S. Postoperative atrial fibrillation (POAF) after cardiac surgery: clinical practice review. J Thorac Dis. (2024) 16(2):1503–20. doi: 10.21037/jtd-23-1626

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

4. Li HO-Y, Smith HA, Brandts-Longtin O, Maziak DE, Gilbert S, Villeneuve P, et al. Variation in management of post-operative atrial fibrillation (POAF) after thoracic surgery. Gen Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. (2021) 69(8):1230–5. doi: 10.1007/s11748-020-01574-1

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

5. Dobrev D, Aguilar M, Heijman J, Guichard JB, Nattel S. Postoperative atrial fibrillation: mechanisms, manifestations and management. Nat Rev Cardiol. (2019) 16(7):417–36. doi: 10.1038/s41569-019-0166-5

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

6. Heijman J, Muna AP, Veleva T, Molina CE, Sutanto H, Tekook M, et al. Atrial myocyte NLRP3/CaMKII nexus forms a substrate for postoperative atrial fibrillation. Circ Res. (2020) 127(8):1036–55. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.120.316710

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

7. Shingu Y, Kubota S, Wakasa S, Ooka T, Tachibana T, Matsui Y. Postoperative atrial fibrillation: mechanism, prevention, and future perspective. Surg Today. (2012) 42(9):819–24. doi: 10.1007/s00595-012-0199-4

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

8. Turagam MK, Mirza M, Werner PH, Sra J, Kress DC, Tajik AJ, et al. Circulating biomarkers predictive of postoperative atrial fibrillation. Cardiol Rev. (2016) 24(2):76–87. doi: 10.1097/CRD.0000000000000059

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

9. Manfrini O, Cenko E, Ricci B, Bugiardini R. Post cardiovascular surgery atrial fibrillation. Biomarkers determining prognosis. Curr Med Chem. (2019) 26(5):916–24. doi: 10.2174/0929867324666170727104930

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

10. Polintan ET, Monsalve R, Menghrajani RH, Sirilan KY, Nayak SS, Abdelmaseeh P, et al. Combination prophylactic amiodarone with beta-blockers versus beta-blockers in atrial fibrillation after cardiac surgery: a systematic-review and meta-analysis. Heart Lung. (2023) 62:256–63. doi: 10.1016/j.hrtlng.2023.08.006

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

11. Turagam MK, Downey FX, Kress DC, Sra J, Tajik AJ, Jahangir A. Pharmacological strategies for prevention of postoperative atrial fibrillation. Expert Rev Clin Pharmacol. (2015) 8(2):233–50. doi: 10.1586/17512433.2015.1018182

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

12. Docherty KF, Vaduganathan M, Solomon SD, McMurray JJV. Sacubitril/valsartan: neprilysin inhibition 5 years after PARADIGM-HF. JACC Heart Fail. (2020) 8(10):800–10. doi: 10.1016/j.jchf.2020.06.020

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

13. Seferovic JP, Claggett B, Seidelmann SB, Seely EW, Packer M, Zile MR, et al. Effect of sacubitril/valsartan versus enalapril on glycaemic control in patients with heart failure and diabetes: a post-hoc analysis from the PARADIGM-HF trial. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. (2017) 5(5):333–40. doi: 10.1016/S2213-8587(17)30087-6

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

14. Alonso A, Morris AA, Naimi AI, Alam AB, Li L, Subramanya V, et al. Use of SGLT2i and ARNi in Patients with Atrial Fibrillation and Heart Failure in 2021–2022: An Analysis of Real-World Data. medRxiv. (2023):2023.09.08.23295280. doi: 10.1101/2023.09.08.23295280 [Preprint].

Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

15. Li Q, Fang Y, Peng D-W, Li L-A, Deng C-Y, Yang H, et al. Sacubitril/valsartan reduces susceptibility to atrial fibrillation by improving atrial remodeling in spontaneously hypertensive rats. Eur J Pharmacol. (2023) 952:175754. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2023.175754

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

16. Mujadzic H, Prousi GS, Napier R, Siddique S, Zaman N. The impact of angiotensin receptor-neprilysin inhibitors on arrhythmias in patients with heart failure: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Innov Card Rhythm Manag. (2022) 13(9):5164–75. doi: 10.19102/icrm.2022.130905

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

17. Mariani MV, Manzi G, Pierucci N, Laviola D, Piro A, D’Amato A, et al. SGLT2i Effect on atrial fibrillation: a network meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Cardiovasc Electrophysio. (2024). doi: 10.1111/jce.16344

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

18. Darweesh RM, Baghdady YK, El Hossary H, Khaled M. Importance of left atrial mechanical function as a predictor of atrial fibrillation risk following cardiac surgery. Int J Cardiovasc Imaging. (2021) 37(6):1863–72. doi: 10.1007/s10554-021-02163-w

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

19. Banach M, Kourliouros A, Reinhart KM, Benussi S, Mikhailidis DP, Jahangiri M, et al. Postoperative atrial fibrillation—what do we really know? Curr Vasc Pharmacol. (2010) 8(4):553–72. doi: 10.2174/157016110791330807

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

20. Oliveira JP, Fragão-Marques M, Lourenço A, Falcão-Pires I, Leite-Moreira A. Adverse remodeling in atrial fibrillation following isolated aortic valve replacement surgery. Perfusion. (2021) 36(5):482–90. doi: 10.1177/0267659120949210

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

21. Wei Y, Zhang Q, Chi H, Wang Z, Chang Q. Effects of recombinant human brain natriuretic peptide on atrial fibrillation after coronary artery bypass grafting. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. (2023) 81(1):63–9. doi: 10.1097/FJC.0000000000001370

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

22. Gaudino M, Di Franco A, Rong LQ, Cao D, Pivato CA, Soletti GJ, et al. Pericardial effusion provoking atrial fibrillation after cardiac surgery: JACC review topic of the week. J Am Coll Cardiol. (2022) 79(25):2529–39. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2022.04.029

留言 (0)