Childhood and adolescence are critical periods for physiological and psychological development with numerous challenges that could impact mental health. Young refugees are reported to have poorer mental health than non-refugee youngsters (1–4), which could be due to the challenges they and their families face as a result of conflict and war, loss of home, and resettlement in unfamiliar surroundings, as well as the challenges associated with new living conditions and social circumstances (4).

Jordan is a Middle Eastern country with an estimated population of 11,300,000 individuals in 2022 (5). Jordan’s population is relatively young, with approximately 44% of its residents being 19 years old or younger (6). Also, Jordan has one of the highest percentages of refugees per capita globally, mostly young population of refugees, with around 54% of refugees 19 years old or younger (6). The majority of refugees in Jordan originate from Syria as a consequence of the 2011 civil war and they usually reside in either refugee camps or urban areas, attending schools under the Ministry of Education’s jurisdiction. This diverse and young population in Jordan highlights the importance of investing in mental health to promote the well-being and healthy development of the younger generation in Jordan. Also, many mental health problems develop in childhood and adolescence and progress later in adulthood, so interventions at a young age are a key factor in improving mental health later in life (7).

A recent scoping review of 28 studies on adolescent mental health in Jordan, encompassing Jordanian, Syrian refugee, and mixed populations, revealed wide variability in the prevalence of mental health conditions (8). The prevalence of depression ranged significantly, from 7.1 to 73.8%, while anxiety rates ranged from 16.3 to 46.8%. Syrian refugee adolescents exhibited markedly higher post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) rates (up to 65.1%) compared to Jordanian non-refugees (16.2%). Emotional and behavioral difficulties were also prevalent, with rates ranging from 11.7 to 52.5%. Despite these estimates, many of the studies had limitations that affect the reliability and generalizability of their findings, including small sample sizes, selection and observer biases, and the use of tools lacking proper validity and reliability. Moreover, existing research predominantly focuses on specific mental health conditions, leaving critical gaps in understanding broader emotional and behavioral problems, health-related quality of life, and help-seeking behaviors among Jordanian children and adolescents in Jordan. This study aimed to address these limitations by providing large-scale estimates of the prevalence of mental health issues and emotional difficulties in children and adolescents in Jordan, while also examining their quality of life and help-seeking behaviors. The findings will offer a more comprehensive perspective on youth mental health and inform future interventions.

2 Methods 2.1 Study design and samplingA national school-based survey was conducted among Jordanian children and adolescents as well as those of other nationalities and groups such as Syrian and Palestinian refugees aged between 8 and 12 years during the period December 2022–April 2023. This study utilized a multi-stage stratified cluster sampling technique to select a nationally representative sample. For school selection, the sample aimed to achieve coverage of basic and secondary education in the Ministry of Education (MoE), the private sector, and the United Nations Relief and Works Agency (UNRWA) for Palestine refugee schools in Jordan. The school population was stratified into different explicit strata. The first level of stratification is governing authority (MoE, private, and UNRWA). Within these strata, there is implicit stratification by region (North, South, and Central) and governorate (12 governorates). Within the MoE stratum, the second level of explicit stratification is the refugee context (Regular MoE schools and Syrian second-shift schools). Regular MoE schools and MoE Syrian second-shift schools are further stratified by gender (boys, girls, and mixed). Because of its small size, half of the Zaatari refugee camp schools were selected and gender balanced.

A list of all schools was obtained from the MoE. Schools were ordered according to the number of students. A systematic sample was selected from each stratum. All classes (grades 3–12) in the selected schools were included and each class was defined as a unit for data collection. A systematic sample of 30% of students in each class was selected. The decision to select 30% of students from each class was made to increase the number of schools in the study, enhancing overall representativeness. This approach allowed broader coverage across regions, school types, and governing authorities, effectively capturing the diversity of the Jordanian educational system. Furthermore, stratified sampling at multiple levels—governance authority, region, refugee context, and gender—ensured adequate representation of variations across schools and regions. The students were selected proportional to the size of students in the governing authority/governorate strata (self-weighted sample). Those who are not attending or dropped from school were reached and oversampled, by including students attending nonformal education centers. Data was collected specifically from nonformal education centers located in the northern and central regions of Jordan, where the majority of students are enrolled in the non-formal education program. The sample of non-formal education centers was gender balanced.

2.2 Sample sizeAssuming the prevalence of the common mental disorder (e.g., depression) in children and adolescents equals 25% with a confidence interval width of 4% and confidence level of 95%, the estimated sample size is 1,801. A design effect of 2 to account for the clustering of the observations and a 70% complete response rate are used to adjust the required sample size. To have adequate power to conduct subgroup analysis, the number of potential participants invited to this survey was increased to 9,000 children and adolescents.

2.3 Data collectionPrior to data collection, data collectors received extensive training on various aspects of the data collection process, including ethical considerations, the importance of maintaining confidentiality, and best communication practices with the target population. Trained data collectors who visited the selected schools handed out the questionnaire to the target groups, including students in grades 7 to 12 (age 12–18 years), or asked students in grades 3 to 6 (age 8–11) to give the questionnaires to their proxy respondents. Data collectors provided clear information about the purpose of the study, voluntary participation, confidentiality, and anonymity. A written informed consent for their participation was obtained from the legal guardians. For students in grades 7 to 12, the students were asked to maintain adequate physical spacing when completing the questionnaires to minimize the risk of social desirability and to ensure genuine responses. Special care was taken to convey the survey information in clear and understandable language. Principals were contacted in advance to arrange data collection. Data collectors stayed with students to answer questions and maintain privacy.

2.4 Study toolsThe choice of the tools was guided by a literature review on the topic and by consultation with a group of experts that included a psychologist, a sociologist, a family physician, and two epidemiologists. The study questionnaires are internationally recognized and validated in English. All standardized questionnaires including the students’ and parents’ versions were used after obtaining the approvals of use from the developer or the ones who own the copyright. The survey included two versions, a proxy parent version for parents of students in grades 3 to 6 and a self-report version for students in grades 7 to 12. For the instruments that have only self-report versions, questions were re-worded by the research team to reflect parents’ responses about their children’s cases.

The selected instruments were translated into the Arabic language using a forward-backward method and culturally adapted, in cases where an Arabic language was unavailable. Two bilingual experts independently performed a forward translation of all questionnaires. Based on a consensus meeting a single preliminary Arabic version was formed. This version was translated back into English independently by two other bilingual experts. An expert committee consisting of two forward translators, one backward translator, two clinical health scientists, and one epidemiologist reviewed the original tools and each translated version, which resulted in a pre-final version of the Arabic tool. Special attention was devoted to the clarity of items to allow for similar cognitive processing by the respondents. The survey was anonymous, and respondents had the right to skip questions or discontinue the survey if questions made them feel uncomfortable.

All selected tools were combined and structured in one questionnaire. The first section of the questionnaire included questions related to schools’ characteristics, socio-demographic characteristics, and health status. The Family Affluence Scale (FAS)-III (9), was used to examine the SES of children and adolescents. FAS is a self-administered questionnaire comprising six items that assess the family material assets or activities (e.g., number of cars and dishwashers). The six questions were revised to fit the country context and only slightly changed by just making them more relevant to the conversational language style in Arabic. The response options for the questions varied depending on the specific question being asked and included the following options and scores: No/Not at all/None = 0, Yes/One/Once = 1, Two/twice = 2, and more than two/ more than twice = 3. The Participants’ responses were summed and ranged from 0 to 13, with higher scores indicating higher levels of affluence. The following ranges were used to categorize the results for both boys and girls: 0–7 (low affluence), 8–11 (medium affluence), and 12–13 (high affluence) (10).

The Revised Child Anxiety and Depression Scale (RCADS) was used to measure symptoms of anxiety and depression in children and adolescents aged between 8 to 18 years (11). The RCADS consists of 47 items rated on a 4-point Likert scale (i.e., never = 0, sometimes = 1, often = 2, and always = 3). The scale yields two total scales, and 6 subscales, corresponding with the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition (DSM-IV) classifications for anxiety and depressive disorders. The 6 subscales include Separation Anxiety Disorder (SAD), Generalized Anxiety Disorder (GAD), panic disorder (PD), Social Phobia (SP), Obsessive Compulsive Disorder (OCD), and Major Depressive Disorder (MDD). The two total scales include the Total Anxiety Score (the sum of the five anxiety subscales) and the Total Internalizing Scale (the sum of all six subscales). The RCADS is available in two versions, a self-report and a parent version, both of which capture symptoms of anxiety and depression across all total scales and subscales (11). RCADS scores were calculated using an automated Excel scoring sheet publicly available by the developer (11). The scoring sheet utilized United States Norms and required input of grades and gender. RCADS was scored using U.S. norms because the RCADS is a widely validated tool that has been extensively used in research settings in the United States, and the available scoring sheet utilizes these established norms. Raw scores were first calculated and then converted to T-scores. In the current study, cut-off points of T scores of 70 or more were used to categorize those with anxiety and depression symptoms for all total scales and subscales, following the recommendations stated in the RCADS user guide (11). According to the guide, a converted score of 70 or more indicates a clinical range of symptoms (i.e., scores above the clinical threshold) (11).

The Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ) was used to assess emotional and behavioral problems. SDG is a brief emotional and behavioral screening questionnaire for children and young people, asking about 25 attributes, some positive and others negative (12). The SDQ is available in self-report and parent versions. Respondents were asked to rate the statements on a 3-point Likert scale (not true, somewhat true, and certainly true), with a mixture of positive and negatively phrased items. The 25 items are divided into 5 scales of 5 items each, generating scores for emotional symptoms, conduct problems, hyperactivity, peer problems, and prosocial behavior, for each of the subscales, the scores can range from 0 to 10 scale. A total difficulties score is generated from the sum of the four sub-scales of emotional symptoms, conduct problems, hyperactivity, and peer problems (20 items). Some items were reversed scored. Subscale scores were only calculated if at least three of the five items had been completed. The cutoff values for defining the abnormal attributes for parents’ versions were as follows: total difficulties score (17–40), emotional problems (5–10), conduct problems (4–10), hyperactivity score (7–10), peer problems (4–10) and prosocial behavior (0–4). The cutoff values for defining abnormal attributes for students’ versions were used as follows: total difficulties (20–40), emotional problems (7–10), conduct problems (5–10), hyperactivity (7–10), peer problems (6–10) and prosocial behavior (0–4). Higher scores on the difficulties subscales (emotional problems, conduct problems, hyperactivity, and peer relationship problems) indicate greater levels of difficulties, whereas higher scores on the prosocial behavior subscale indicate positive social behavior.

The Children’s Impact of Event Scale-13 (CRIES-13) was used to assess symptoms of childhood PTSD. It is a 13-item measure and can be used with children 8 years and older (13, 14). CRIES-13 is a self-report scale; therefore, a proxy parent version was developed by rewording the self-report scale to reflect the parents’ experiences or perceptions of the occurrence of various comments of people who had stressful lives in the case of their children. The scale consists of an overall scale and three subscales with 4 items measuring intrusion, 4 items measuring avoidance, and 5 items measuring arousal. Items are scored on a four-point nonlinear scale: not at all (0), rarely (1), sometimes (3), and often (5). The overall CRIES score is the total sum of all items. A cut-off score of 30 on the total scale was described as effective for screening cases of PTSD (13) and was therefore used to categorize those with PTSD symptoms from those without.

The Pediatric Quality of Life Inventory (PedsQL) was used to assess quality of life. It is a 23-item scale measuring the health-related quality of life in children and adolescents (15). It assesses five domains including physical functioning (eight items), emotional functioning (five items), social functioning (five items), and school functioning (five items). It includes core health dimensions delineated by the World Health Organization (WHO), including role (school) functioning. It has three Summary Scores including, Total Scale Score (23 items), Physical Health Summary Score (8 items), and Psychosocial Health Summary Score (15 items). The generic core scales have parallel child self-report and parent proxy-report formats. Items are rated on a 5-point Likert scale from 0 (never) to 4 (almost always), with a higher score indicating a better health-related quality of life. Items are scored in reverse order and then linearly converted to a 0–100 scale as follows: 0 = 100, 1 = 75, 2 = 50, 3 = 25, 4 = 0. Published cutoff scores were used to categorize the poor quality of life across all domains, including total, physical, emotional, social, and school functioning domains. For scores less than 78, 88, 75, 80, and 70 in the respective domains, individuals were classified as having poor quality of life (16). Higher scores indicate a better quality of life. The General Help-Seeking Questionnaire (GHSQ) is a two-item questionnaire (17) that was used to assess the intention to seek help from a variety of sources and for a variety of problems. The original version contains two questions that capture the intention to seek help and sources of help for general personal and emotional problems and suicidal ideation. Respondents are asked to rate the likelihood of seeking help from formal or informal help sources, on a 7-point Likert scale ranging from 1 = very likely to 7 = very unlikely. GHSQ uses a matrix format that can be modified according to the characteristics of the sample and the needs of the study. In this study, the GHSQ was revised and changed as follows: First, only the question about personal and emotional problems was included as it relates to the goal of the study, with binary responses (yes, no) to identify the most common sources of help for those who wish to seek help. The sources of help were adjusted to reflect the known sources of help for mental health problems among children, adolescents, and parents in Jordan, based on the recommendation of the study’s expert panel. Because the GHSQ is a self-report questionnaire, the research team developed a proxy version for parents of children by rewording the self-report version to capture their intention to seek help for their children’s problems and sources of help. There is no Arabic version for this scale, so the research team conducted a forward-backward translation for both versions. The modifications on the tool involved language translation and cultural adaptations to ensure that the items were relevant and comprehensible for children and adolescents in Jordan. The modified versions of these tools were also pilot-tested.

The Barriers to Adolescents Seeking Help Scale—Brief Version (BASH-B) is an 11 items scale that presents reasons why adolescents might not seek professional help by representing barriers relating to self-sufficiency, embarrassment, time, and money constraints, not wanting family to know, the belief that nothing will help, confidentiality breaches, and coercion (18). In this study, the BASH -B was revised and changed as follows: 9 additional barriers were added to the 11 items to account for the religious and cultural barriers that play a major role in shaping attitudes in the Jordanian context. Answers were changed from Likert score form to binary (yes, no) to establish a clear quantification of each barrier. Furthermore, the scale was modified to focus on reasons for not seeking care rather than barriers. Because the BASH-B is a self-report questionnaire, a proxy version for parents was developed by rewording the self-report version to report parents’ reasons for not seeking mental health help for their children’s problems. There is no Arabic version for this scale, so the research team conducted a forward-backward translation for both versions. The modified versions of these tools were also pilot-tested.

Short questions were used to address diet. The questions were adapted from the Many Rivers Short Food Frequency Questionnaire (MRSSFQ) (19). Four questions were used to explore dietary habits in terms of the frequency of eating fruit and vegetable servings per day. One fruit serving was defined as 1 medium piece or 2 small pieces of fruit and this includes all fresh, dried, frozen, and tinned fruit. One vegetable serving was defined as half a cup of cooked vegetables or 1 cup of salad vegetables. Additionally, junk food consumption frequency was examined using names that are commonly used in Jordan. A fourth question addressed dietary behavior in terms of eating while watching TV, or on mobile phones or tablets.

Short questions on physical activity that have been validated by Prochaska et al. (20) were used. Four questions were used to examine the frequency of weekly engagement in light and vigorous physical activity and the estimated time spent watching TV, mobile phones, or tablets for entertainment purposes.

The “BEARS” instrument was used to assess sleep disorders. It is divided into five major sleep domains, providing a comprehensive screen for the major sleep disorders affecting children in the 2 to 18 years old range (21). Each sleep domain has a set of age-appropriate “trigger questions” for use in the clinical interview. B = bedtime problems E = excessive daytime sleepiness A = awakenings during the night R = regularity and duration of sleep S = Snoring. The research team developed an Arabic version for this scale using forward-backward translation for parents and children versions.

The Problematic Internet Use Questionnaire (PIUQ-6) was used to assess three key factors in problematic internet use (PIU), including obsession (i.e., obsessive thinking about the internet and mental withdrawal symptoms caused by the lack of internet use), neglect (i.e., neglect of basic needs and everyday activities), and control disorder (i.e., difficulties in controlling internet use) (22). A 5-point Likert scale (“never,” “rarely,” “sometimes,” “often,” and “always/almost always”) is used to evaluate how much the given statements characterized the respondents. Scores range from 6 to 30, with higher scores indicating a higher risk of PIU. Since the PIUQ-SF-6 is a self-report questionnaire, a proxy version for parents was developed by rewording the self-report version to report parents’ perspectives. In the current study, a cut-off score of higher than 15 was used to classify those at risk of problematic Internet use, based on the acceptable sensitivity and specificity analyses of one study (22).

Three questions were asked to assess smoking and tobacco use, including the use of conventional cigarettes, electronic cigarettes, and waterpipe (shisha). For each product, a user was defined as a daily or occasional user of the product (i.e., answering every day or some days).

2.5 Pilot testingA pilot test was conducted to evaluate the content of the surveys and the data collection process. The pilot testing was conducted in two schools in Irbid and Mafraq in northern Jordan on November 7th, 2022. The school in Irbid is a girls’ school for Jordanian nationals and the school in Al Mafraq is located in the Zaatari camp for Syrian refugee boys. A total of 30 students from grades seven to twelve, 15 from each school, were asked to complete the student questionnaire, and 30 children from grades three to six, 15 from each school, were asked to send the questionnaire to their parents. The changes identified in the piloting phase were reflected into the parent and student versions in both languages.

2.6 Quality assuranceThe main researchers were conducting regular data quality assurance by comparing the data entered with the responses on the paper-based questionnaires, along with setting restrictive data ranges on the Excel sheets. The main researchers observed data collection over the course of the study to ensure adherence to data collection procedures. To ensure systematic quality monitoring, a checklist of key data collection quality indicators was used, including whether students were informed of the survey prior to the start of data collection.

2.7 Ethical issuesThis survey followed the “Declaration of Helsinki” and other relevant local ethical guidelines for medical and health research involving human subjects. Participants and their caregivers were fully informed by the document explaining the details of the study purpose, methods, ethical considerations, the voluntariness of their participation, and that they could withdraw at any time without explanation. All participants were informed that participation is voluntary and that all data will be kept in a safe, locked cabinet with only limited access by the project team. Similarly, participants were informed that if participation causes any stress or discomfort, they could withdraw from the study without any ensuing penalties and conditions. Written informed consent from the caregiver of the participants and informed assent from the participants were obtained. Ethical approvals were obtained from the Institutional Research Committees at Jordan University of Science and Technology (JUST), and Jordan Ministry of Health (MoH).

2.8 Statistical analysisData analysis was carried out using IBM SPSS 24 (IBM Corp. Released 2016. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 24.0. Armonk, NY: IBM Corp.). Frequencies and percentages were used to describe categorical variables. Internal consistency of the scales and subscales was evaluated using Cronbach’s alpha. Values above 0.7 were usually used to indicate good measure (23). The Cronbach’s alphas of the RCADS were good for all subscales and ranged from 0.68 to 0.82 for the parent-report version and from 0.70 to 0.88 for the self-report version, whereas the Cronbach’s alphas for total anxiety were excellent at 0.92 for the parent-report version and 0.94 for the self-report version. For the subscales of the SDQ, Cronbach’s alphas ranged from 0.37 to 0.71 for the parent-report version and 0.38 to 0.73 for the self-report version, indicating good internal consistency for some scales, such as emotional symptoms and prosocial behavior in both versions (~0.70), while the Cronbach’s alphas for overall difficulties were good at 0.80 for the parent-report version and 0.78 for the self-report version. The other scales and subscales assessed, including CRIES-13, the PedsQl subscales, and the total problematic Internet use scale, all had excellent internal consistency, ranging from 0.81 to 0.88 in the parent-reported version and from 0.82 to 0.88 in the self-reported version. Cronbach’s alphas for the total scale AQ were 0.66 for the parent-report version, and 0.63 for the self-report version, indicating questionable reliability.

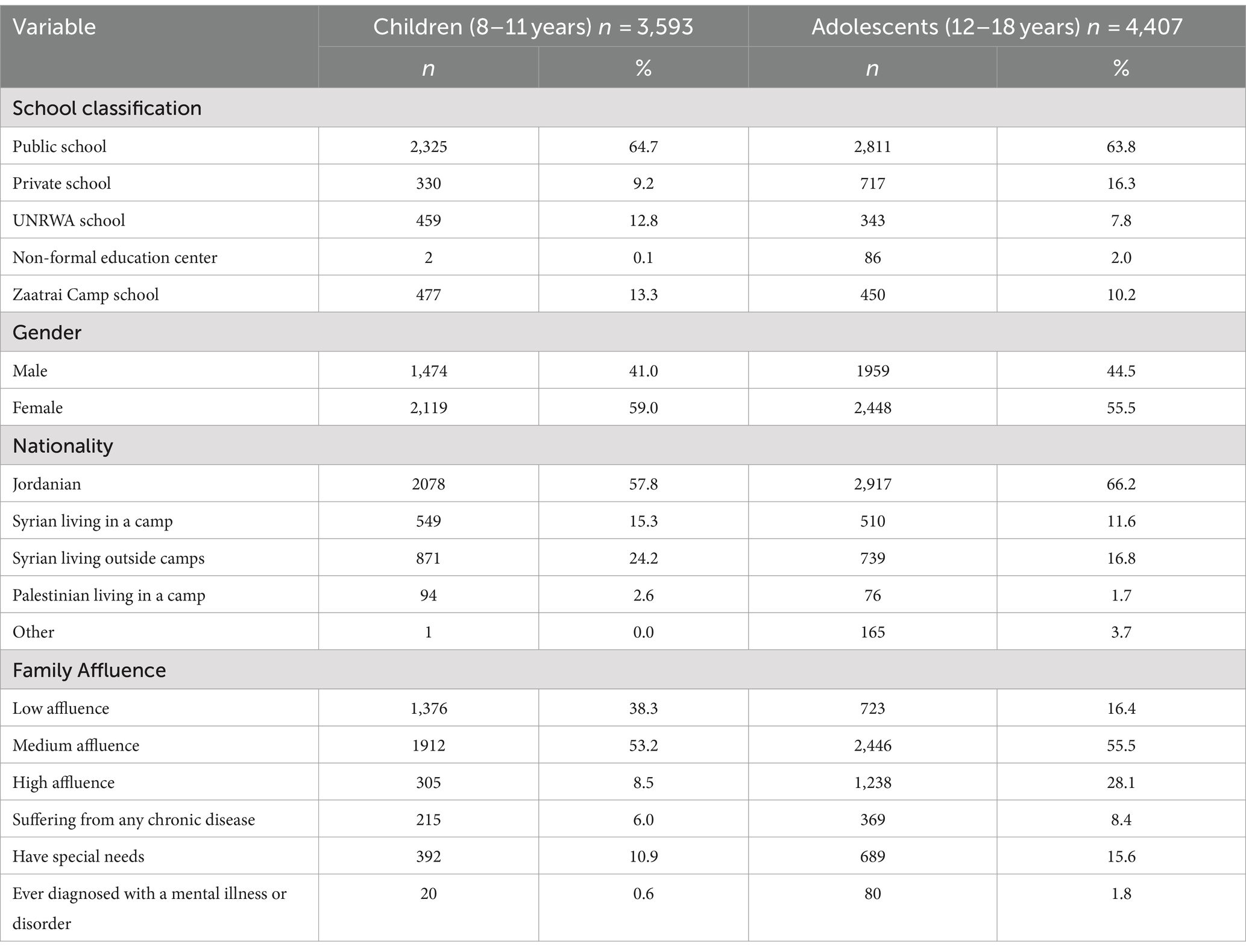

3 Results 3.1 Children’s and adolescents’ characteristicsOf a total of 9,020 children and adolescents, 8,000 (3,433 (42.9%) boys and 4,567 (57.1%) girls) (children aged 8–11 and adolescents aged 12–18 years) responded and completed the study questionnaire. Of those, 3,593 (44.9%) were children and 4,407 (55.1%) were adolescents. Jordanians made up the largest group in the sample (57.8% of children and 66.2% of adolescents), followed by Syrian individuals living outside the refugee camps (24.2% of children and 16.8% of adolescents). Table 1 shows the socio-demographic characteristics and health status of the 8,000 children and adolescents.

Table 1. The socio-demographic characteristics and health status of 8,000 children and adolescents living in Jordan.

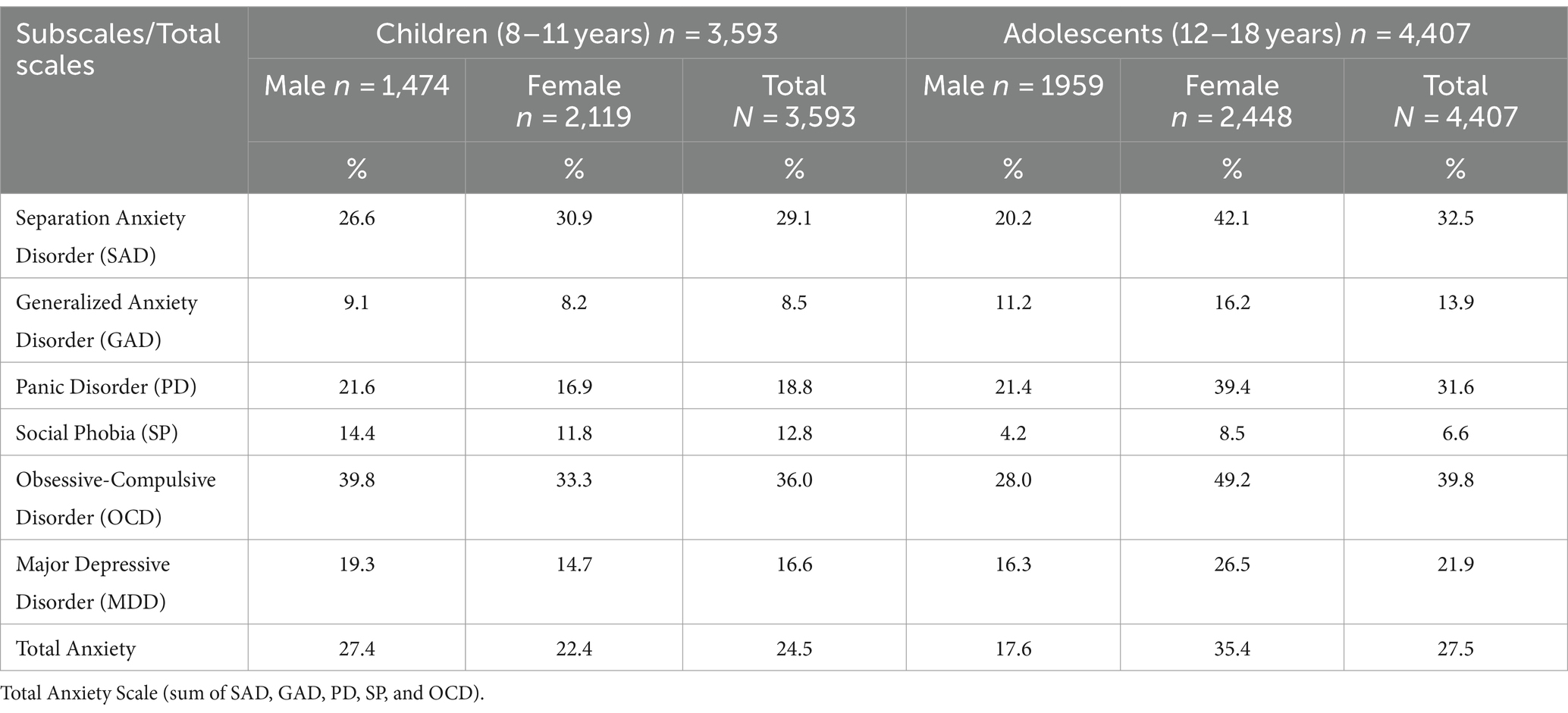

3.2 Anxiety and depressionApproximately one-quarter of the included children (24.5%) and adolescents (27.5%) exhibited anxiety symptoms, while a lower rate of 16.6% in children and 21.9% in adolescents exhibited symptoms of major depressive disorder. Table 2 shows the prevalence rates of depression and anxiety symptoms across all subscales and total scales, by gender. In the children’s group and across all anxiety subscales, the prevalence of obsessive-compulsive disorder symptoms was the highest (36.0%), followed by separation anxiety disorder (29.1%), panic disorder (18.8%), social phobia (12.8%), and generalized anxiety disorder (8.5%). Similarly, the prevalence of obsessive-compulsive disorder symptoms was the highest among adolescents (39.8%), followed by separation anxiety disorder (32.5%), panic disorder (31.6%), generalized anxiety disorder (13.9%), and social phobia (6.6%). In all subscales and total scales, the percentage of adolescents with anxiety or depression symptoms was higher in females than in males, especially in separation anxiety (42.1% vs. 20.2%) and obsessive-compulsive disorder (49.2% vs. 28.0%).

Table 2. The prevalence of depression and anxiety symptoms among children and adolescents by gender.

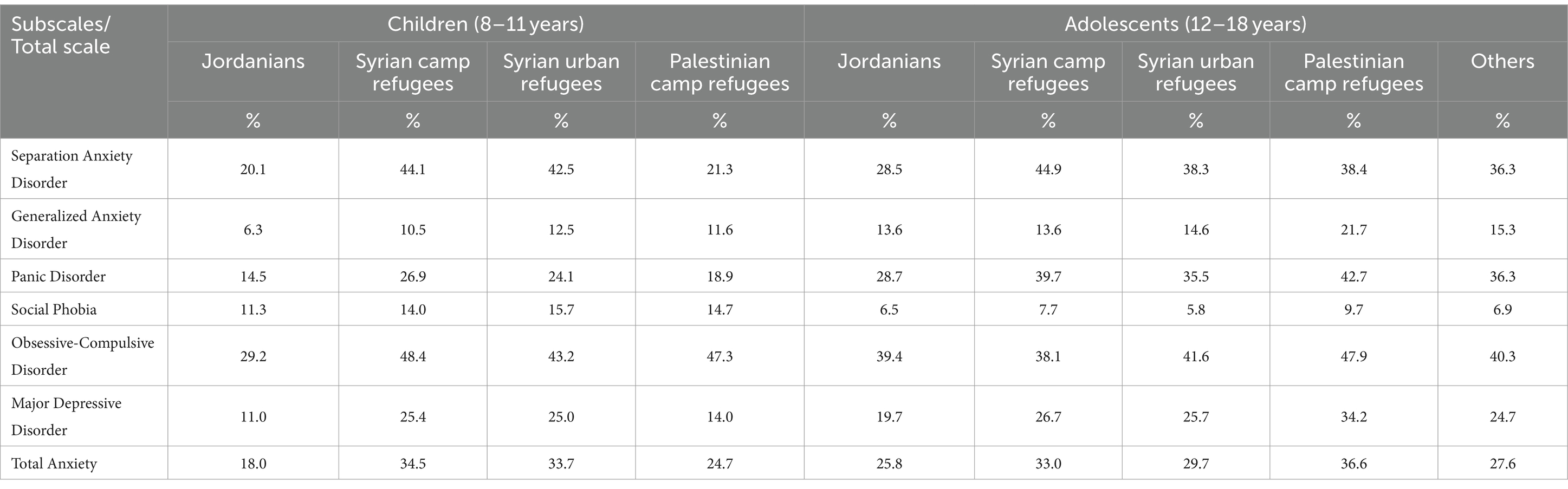

Table 3 shows the prevalence of anxiety and depression symptoms in children and adolescents according to their nationality. Among children, Syrian nationals, including Syrian urban refugees living outside camps and Syrian camp refugees, had the highest rates of depression and anxiety symptoms across all scales and subscales. Separation anxiety symptoms were most common in Syrian camp refugees (44.1%), generalized anxiety disorder in Syrian urban refugees (12.5%), panic disorder in Syrian camp refugees (26.9%), Social phobia in Syrian urban refugees (15.7%), obsessive-compulsive disorder in Syrian camp refugees (48.4%), major depressive disorder in Syrian camp refugees (25.4%), and total anxiety in Syrian camp refugees (34.5%). Among adolescents, non-Jordanians had the highest rates of depression and anxiety symptoms. Palestinian camp refugees in particular had the highest rates across various scales, including obsessive-compulsive disorder symptoms (47.9%), panic disorder (42.7%), total anxiety (36.6%), major depressive disorder (34.2%), and social phobia (9.7%).

Table 3. Anxiety and depression symptoms among children and adolescents according to nationality.

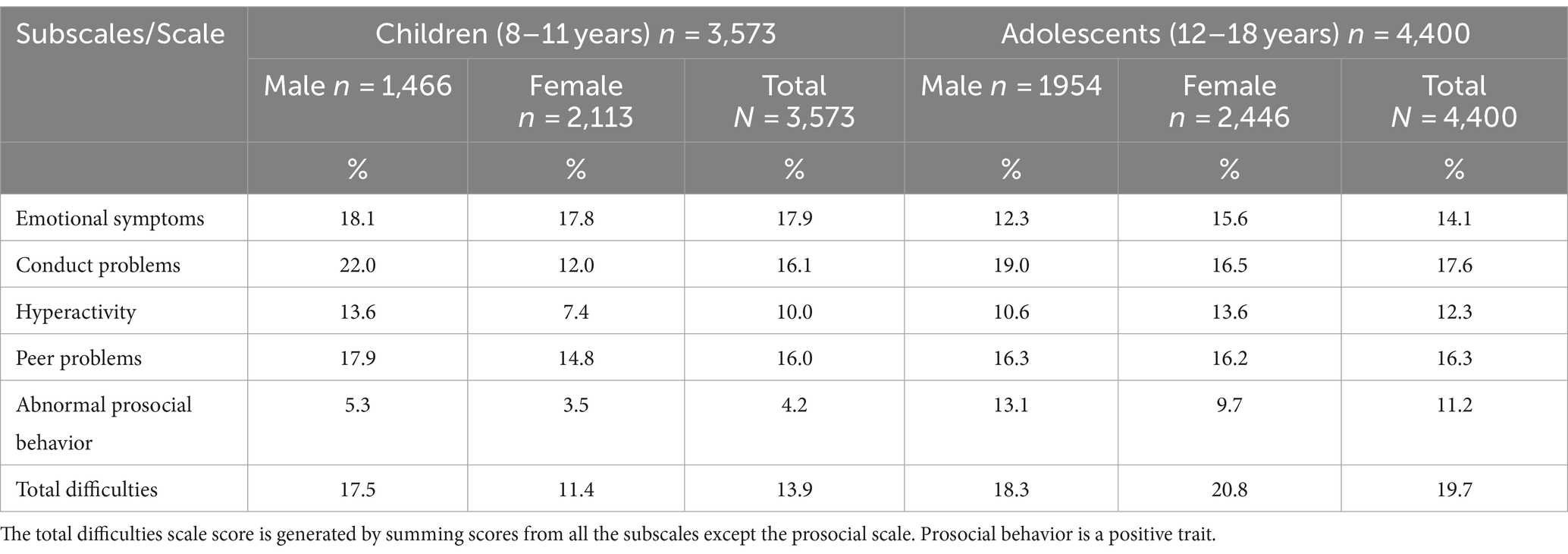

3.3 Emotional and behavioral problemsThe total difficulties score was abnormally high in 13.9% of children and 19.7% of adolescents. Table 4 summarizes the prevalence of emotional and behavioral problems among children and adolescents by gender. The largest percentage of children had abnormal levels of emotional problems (17.9%), conduct problems (16.1%), peer problems (16.0%), and to a lesser extent, hyperactivity (10.0%) and prosocial behavior (4.2%). The largest percentage of adolescents had abnormal levels of conduct problems (17.6%), peer problems (16.3%), emotional problems (14.1%), and to a lesser extent, hyperactivity (12.3%), and prosocial behavior (11.2%).

Table 4. The emotional and behavioral problems among children and adolescents by gender.

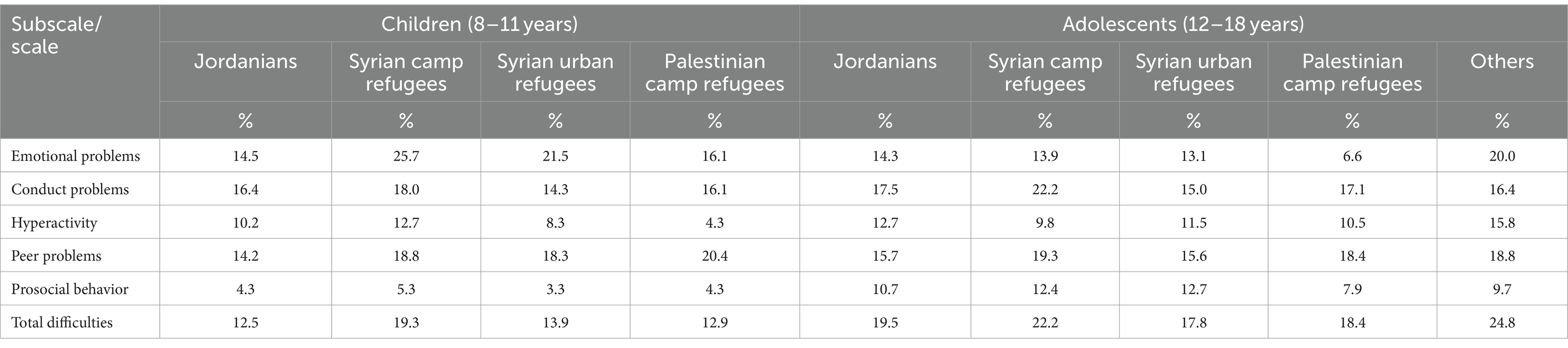

Table 5 shows the prevalence of behavioral and emotional symptoms in children and adolescents by nationality. Syrian children and adolescents living in a camp had higher abnormal overall difficulties than Jordanians, Syrian urban refugees, and Palestinian camp refugees, at 19.3 and 22.2%, respectively. Among children, Syrian camp refugees were the group with the highest rates of emotional problems (25.7%), conduct problems (18.0%), hyperactivity (12.7%), and abnormal prosocial behavior (5.3%). However, the peer problem rate was highest among Palestinian refugees (20.4%). Among adolescents, Syrian camp refugees displayed the highest rates of conduct problems (22.2%) and peer problems (19.3%). Notably, Jordanians had the highest rates of emotional problems (14.3%) and hyperactivity (12.7%). Additionally, Syrian urban refugees had the highest levels of abnormal prosocial behavior (12.7%).

Table 5. Behavioral and emotional symptoms among children and adolescents according to nationality.

3.4 Post-traumatic stress disorder symptomsThe prevalence of PTSD was 24.6% among children (26.0% among males and 23.6% among females) and 35.5% among adolescents (31.1% among males and 38.9% among females). PTSD symptoms were more common in non-Jordanian children and adolescents. Among children, PTSD symptoms were more common among Syrians living outside camps (30.2%) and Syrian camp refugees (27.4%) than among Jordanian children (21.5%) and Palestinian refugee children (20.0%). Among adolescents, PTSD symptoms were more common among Palestinian camp refugees (37.7%), followed by Syrian camp refugees (36.4%), Jordanian children (36.4%), and Syrian urban refugee adolescents (33.8%).

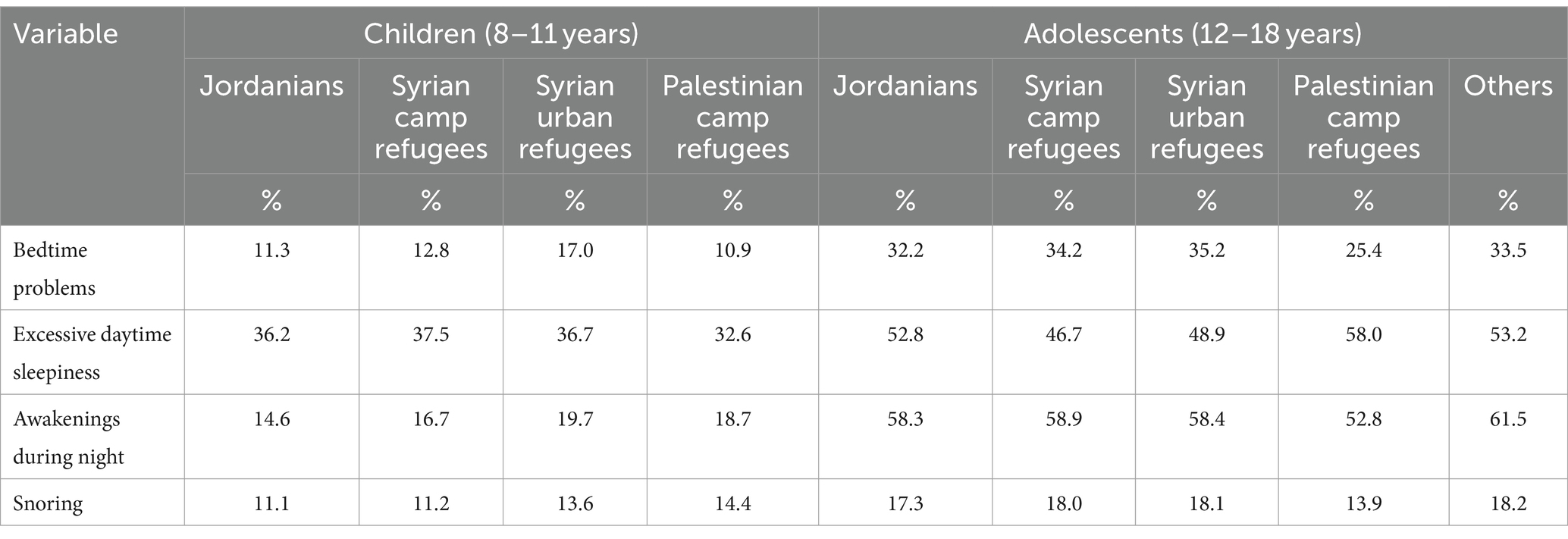

3.5 Sleeping problemsAmong children, the most common sleeping problem was excessive daytime sleep (36.4%). Among adolescents, most sleeping problems were critically high, specifically excessive daytime sleepiness, and nighttime awakenings, which were reported in about half of adolescents. Among different nationalities of children, problems falling asleep and night awakenings were most common among Syrian urban refugees, 17.0 and 19.7%, respectively. Snoring was more common among Palestinian camp refugees (14.4%). However, excessive daytime sleepiness was prevalent in about one-third of all nationalities, with rates ranging from 32.6 to 37.5%. Among different nationalities of adolescents, all sleeping problems were of relatively similar rates while being critically high for excessive daytime sleepiness, and nighttime awakening. Table 6 shows the percentages of sleeping problems among children and adolescents by their nationality group.

Table 6. Sleeping problems among children and adolescents according to nationality.

During school days, a small percentage of children were sleeping insufficiently for less than 7 h (12.2%), compared to about one-third of adolescents who were sleeping insufficiently for less than 7 h (36.9%) during school days. On weekend days, however, the percentage of those who sleep insufficiently for less than 7 h was lower than on school days, at 11.4% among children and 21.5% among adolescents.

3.6 Problematic internet useThe percentage of children and adolescents at risk of problematic internet use was 34.8% (37.9% for males and 32.7% for females) and 45.9% (46.2% for males and 45.6% for females), respectively. The percentage of children at risk for problematic Internet use was higher among Jordanians (38.4%), Syrian urban refugees (34.8%), and Palestinian camp refugees (38.5%) compared with Syrian camp refugees (19.9%). Among adolescents, 46.0% of Jordanians, 42.3% of Syrian camp refugees, 46.2% of Syrian urban refugees, and 50.0% of Palestinian camp refugees were at risk of problematic Internet use.

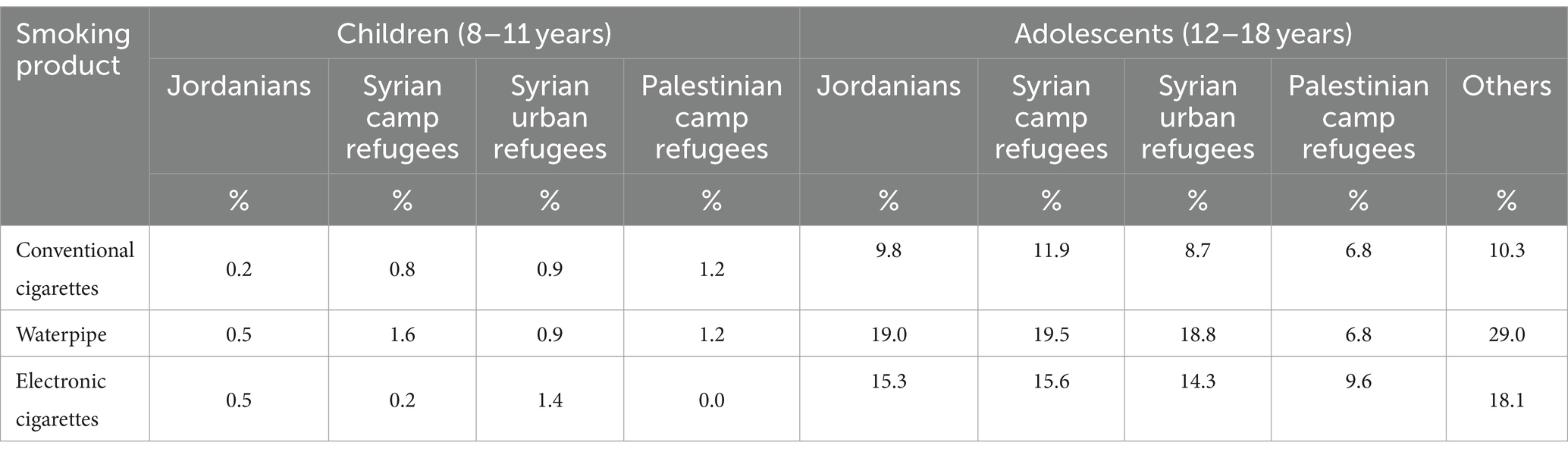

3.7 Tobacco useIn adolescents, waterpipe was the most frequently used tobacco product (19.2%), followed by electronic cigarettes (15.1%), and conventional cigarettes (9.8%). The prevalence of smoking in children and adolescents by their nationality group is shown in Table 7. Waterpipe smoking was most prevalent among adolescents of other nationalities (29.0%), followed by comparatively similar percentages among Syrian camp refugees (19.5%), Jordanians (19.0%), and Syrian urban refugees (18.8%), compared with 6.8% among Palestinian camp refugees. Electronic cigarettes were more used by adolescents of other nationalities (18.1%), and to a similar extent by Jordanians, Syrian camp refugees, and Syrian urban refugees, compared with 9.6% among Palestinian camp refugees. Cigarette smoking was most prevalent among Syrian camp refugees (11.9%).

Table 7. Smoking percentages according to nationality among children and adolescents.

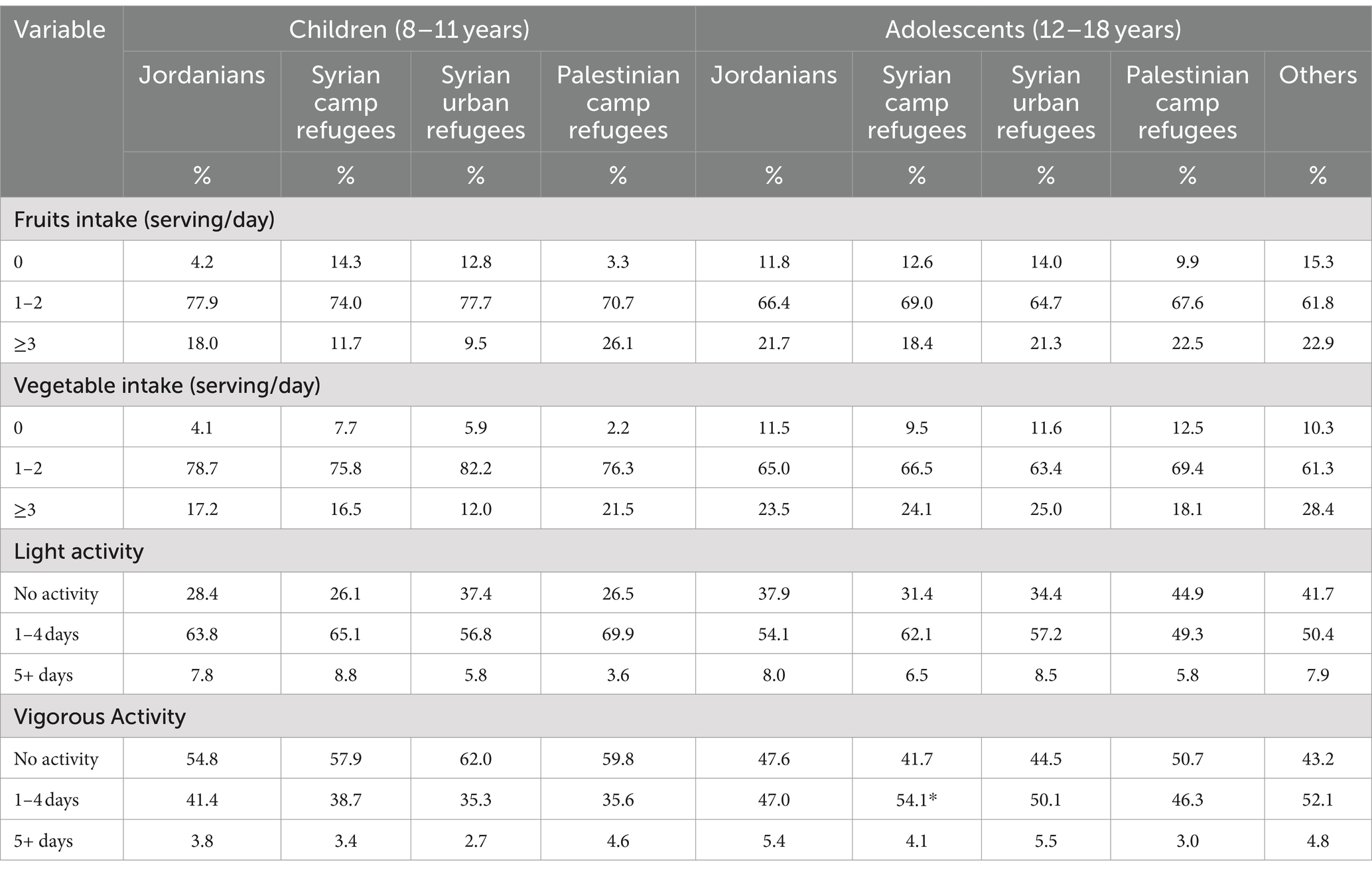

3.8 Diet and physical activityOnly 15.2 and 16.0% of children and 21.3 and 23.9% of adolescents eat ≥3 servings of fruits and ≥ 3 servings of vegetables per day, respectively. Among children, Syrian refugees in urban areas and camps were the groups with the lowest percentage of children eating ≥3 servings of fruits and vegetables. Among adolescents, the proportion of those eating ≥3 servings of fruit was also the lowest among Syrian refugees in camps and urban areas, whereas the proportion of those eating ≥3 servings of vegetables was lowest among Palestinian refugees in camps.

About one-third of children (30.3%) and adolescents (36.9%) do not engage in any form of light physical activity per week, with a higher proportion among Syrian children in urban areas (37.4%) and adolescents from Palestinian refugee camps (44.9%). Also, about one-half of children (57.1%) and adolescents (46.3%) do not engage in any form of vigorous physical activity per week, with higher proportions among Syrian children in urban areas (62.0%) and adolescents from Palestinian camps (50.7%), as shown in Table 8.

Table 8. Diet and Physical activity among children and adolescents according to nationality.

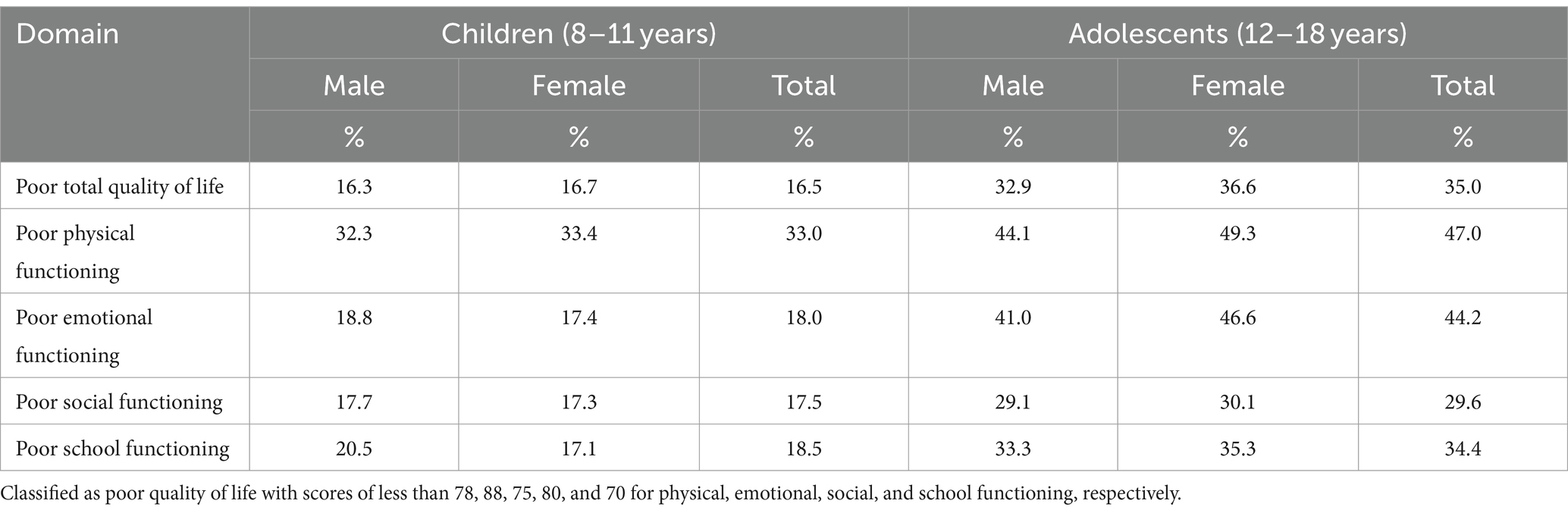

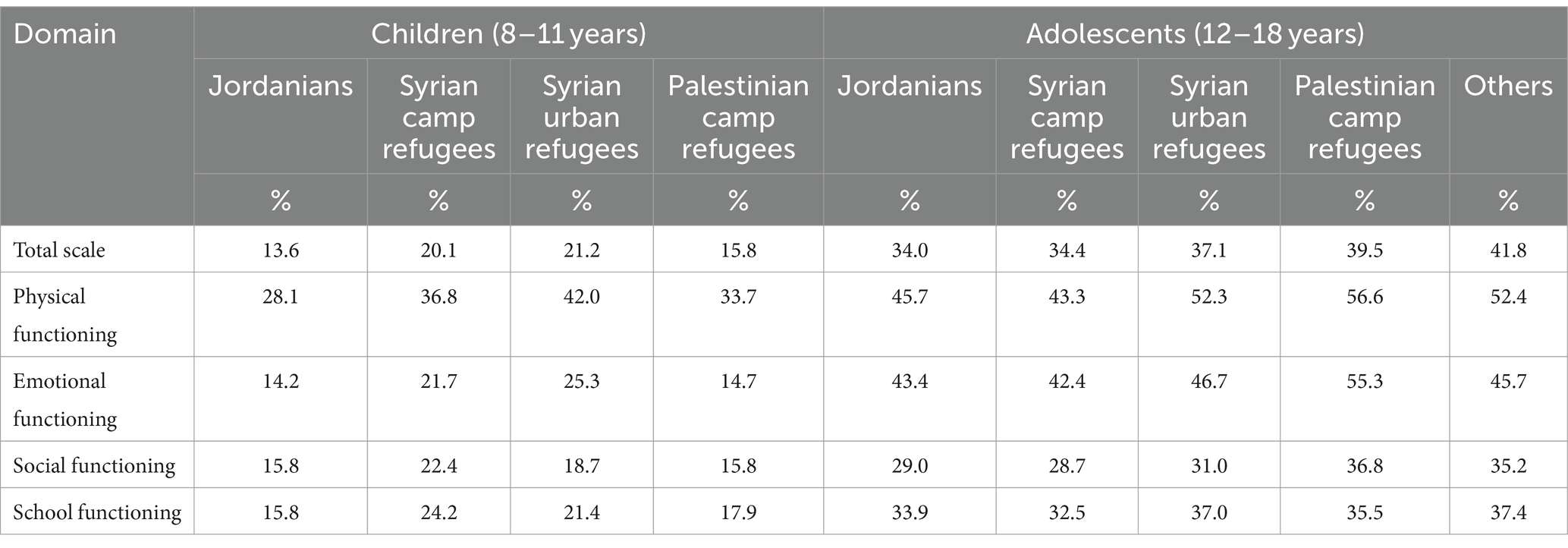

3.9 Quality of lifeThe percentages of children and adolescents with poor quality of life are shown in Table 9. Nearly 16.5% of children and 35.0% of adolescents had an overall poor quality of life. Among children, the largest percentage of respondents had poor physical functioning (33.0%). Similarly, among adolescents, the largest percentage of respondents (47.0%) had poor physical functioning. However, the percentages of poor quality of life were generally high across all other domains for adolescents, particularly emotional functioning (44.2%). Among adolescents, females had a higher percentage of poor quality of life in all domains.

Table 9. The percentages of poor quality of life domains among children and adolescents by gender.

Table 10 shows the prevalence of poor quality of life in children and adolescents according to nationality. Among children, Syrians had the highest rates across all domains, with Syrian urban refugees having the highest rates of overall poor quality of life, poor physical functioning, and poor emotional functioning, at 21.2, 42.0, and 25.3%, respectively. Poor social functioning and poor school functioning were the highest among Syrian camp refugees at 22.4 and 24.2%, respectively. Among adolescents, Palestinian refugees had higher rates than other nationalities in some domains, including poor physical functioning (56.6%), poor emotional functioning (55.3%), and social functioning (36.8%).

Table 10. Poor quality of life among children and adolescents according to nationality.

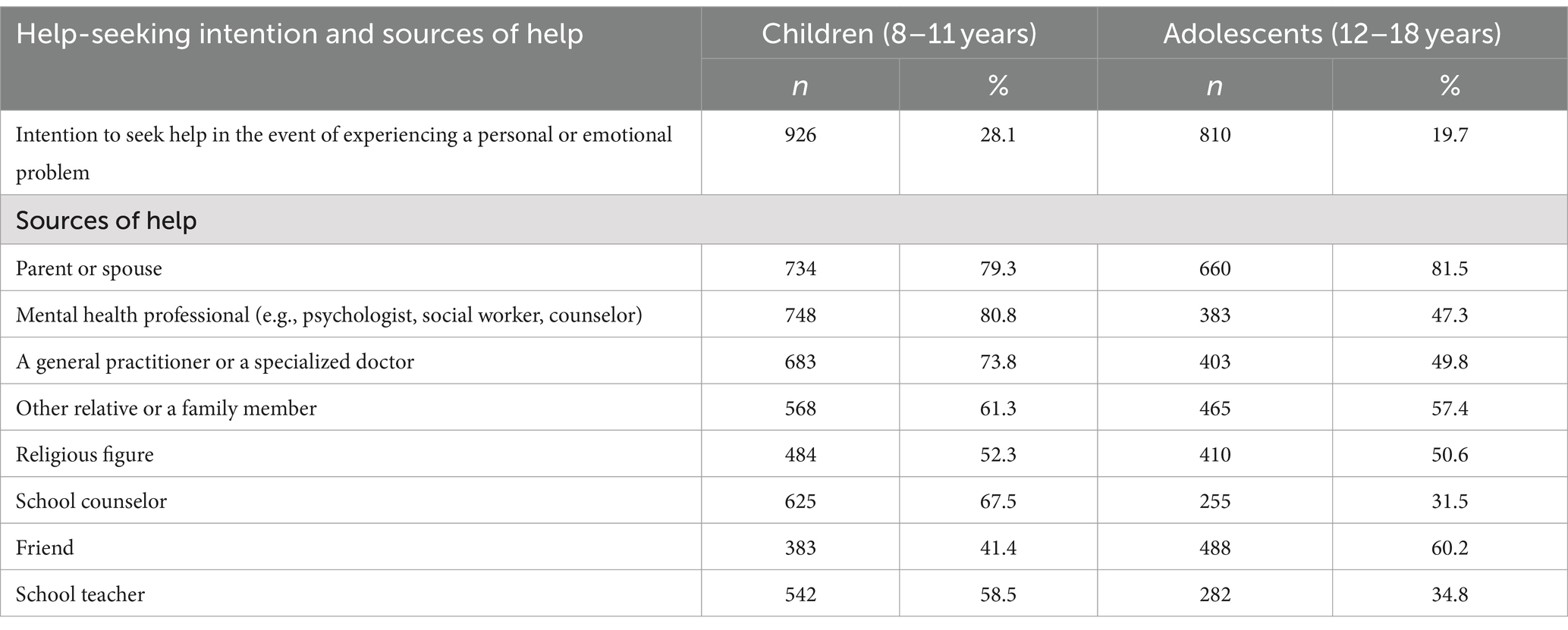

3.10 Mental health care seeking behaviorIn the event of experiencing a personal or emotional problem, approximately one quarter (23.4%) of both parents and adolescents reported that they would seek help, with a higher percentage reported by children’s parents (28.1%) compared to adolescents (19.7%). Table 11 shows mental health help-seeking intentions and sources among children and adolescents. Among parents who would seek help for their children, the majority mentioned they would turn to mental health professionals (80.8%), followed closely by the current or previous spouse (79.3%) then to a lesser extent to a general practitioner or a specialized doctor (73.8%) and school counselor (67.5%). Among adolescents, they would first turn to their parents (81.5%), followed by friends (60.2%), relatives or family members (57.4%), and religious figures (50.6%). However, school counselors and schoolteachers were the least preferred sources of help among adolescents, with only 31.5 and 34.8% of adolescents would seek their help, respectively.

Table 11. Mental health help-seeking intention and sources among children and adolescents and associated factors.

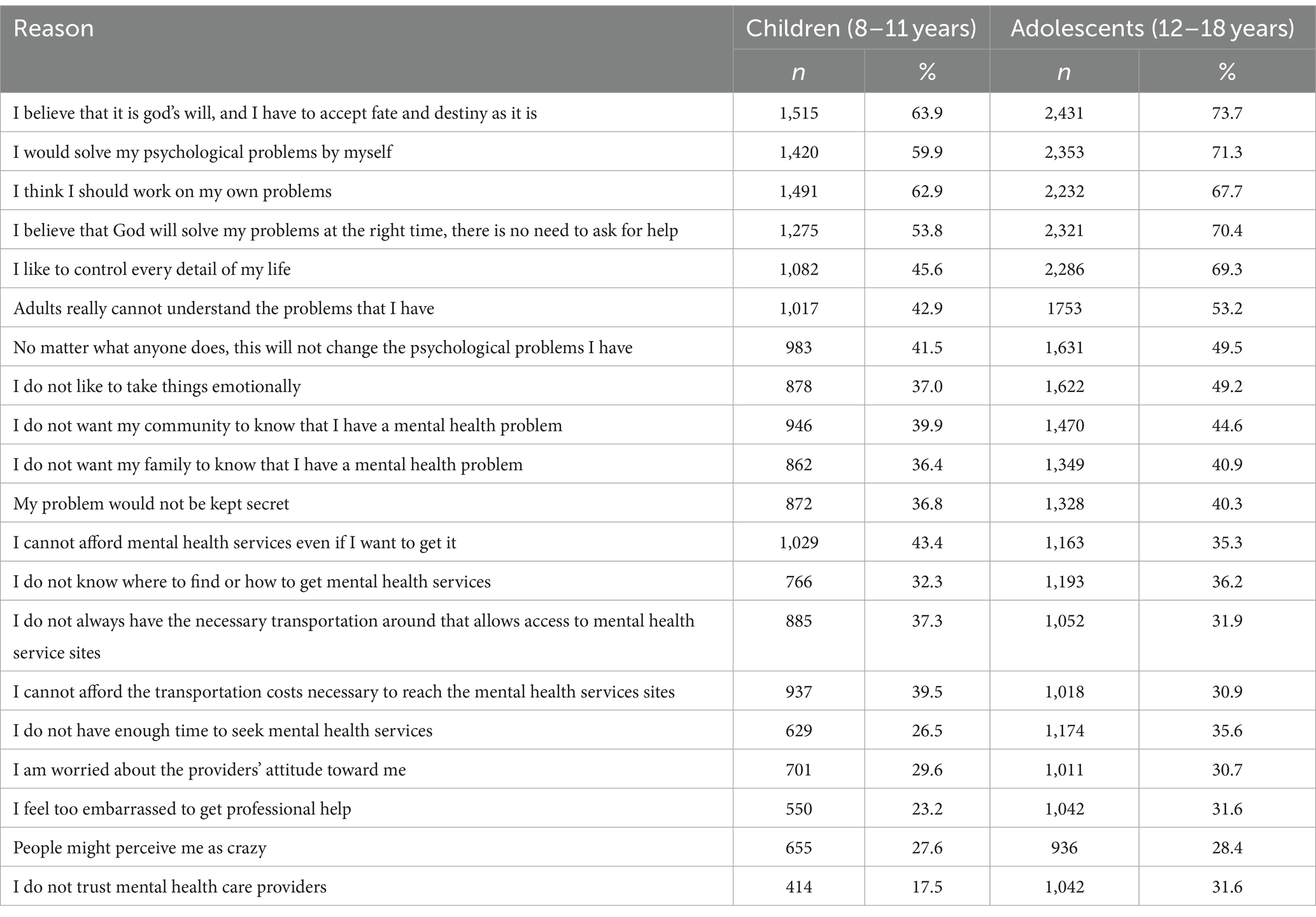

3.11 Reasons for not seeking mental health servicesIn the case of not intending to seek help when children have a personal or emotional problem, the most frequently reported reason by children’s parents was the belief that it is god’s will, and they have to accept fate and destiny as it is (63.9%), the belief that they need to work on their child’s problems (62.9%), parents would solve their child’s psychological problems by themselves (59.9%), and the belief that God will solve the child’ problems at the right time (53.8%). Among adolescents who were unwilling to seek help, the most frequently reported reason was the belief that it is god’s will, and they have to accept fate and destiny as it is (73.73%) and they would solve their psychological problems by themselves (71.3%). Table 12 shows the frequency of a variety of reasons for not seeking mental health services among children and adolescents.

Table 12. Reasons for not seeking mental health services among children and adolescents who did not intend to seek help in the event of experiencing a personal or emotional problem.

4 DiscussionThis study presents the main findings of a large-scale representative national survey aimed at assessing the prevalence rates of psychosocial, emotional, and behavioral problems and their symptoms among children and adolescents in Jordan. The results show a relatively high prevalence of mental health problems and symptoms among the included adolescents compared to children, and among female adolescents compared to their male counterparts. In children, rates of symptoms were generally higher among non-Jordanians, particularly Syrians, while rates were comparatively similar among adolescents of all nationalities, with particularly high rates among Syrians and Palestinians in some cases.

Understanding the underlying causes of mental health outcomes in our target population requires a multifaceted approach that considers cultural, economic, and social mechanisms. Culturally, the stigma associated with mental illness often prevents individuals from seeking help. Economically, individuals facing financial instability may experience heightened stress, exacerbating mental health issues. Socially, the presence or absence of strong support networks plays a critical role; individuals with robust social ties tend to report better mental health outcomes, as supportive relationships can provide emotional comfort and practical assistance during times of crisis.

4.1 Anxiety and depressionThe RCADS was used to assess anxiety and depression as a screening tool, which has been reported to be a reliable tool for assessing symptoms of anxiety and depression in children and adolescents in different assessment settings, countries, and languages (24). Depression disorders’ symptom rates ranged from 8.5 to 36.0% in children and from 6.6 to 39.8% in adolescents. Anxiety symptoms were exhibited in about a quarter of children and adolescents.

Previous studies in Jordan reported similarly high rates ranging from 16.3 to 46.8% for anxiety (25–27) and between 7.1 to 73.8% for depression (25–30). However, the reported prevalence rates in previous studies varied significantly due to the use of different assessment tools for screening anxiety and depression, limited representativeness of the samples, and differences in the populations studied. Thus, comparing estimates between previous studies can be difficult. Compared to the results of the “Youth Wellbeing Prevalence Survey 2020,” that used RCADS and the same clinical threshold, the overall prevalence estimates were lower among children and adolescents aged 2 to 19 years living in Northern Ireland, and the ranking of the most common disorders’ symptoms also varied (31). Different rates could be due to micro-level factors, including differences in parents and adolescents’ attitudes toward mental health, and macro-level factors, including the availability and accessibility of mental health services.

Female adolescents showed higher rates of anxiety and depression symptoms compared to males in adolescents, reflecting a similar trend in the majority of subscales in the adolescent population specifically in Northern Ireland (32). Females having higher rates than males can be explained by different factors, all of which are interrelated and could be shared with other countries or be only specific to Jordan. At the societal level, extreme practices of gender discrimination and inequality, as well as extreme traditional gender roles practiced in some communities, may limit girls’ personal development, autonomy, and self-expression, which may contribute to psychological problems such as anxiety. In addition, puberty is a time of remarkable physical changes when certain gender stereotypes and beauty perceptions can be imposed on girls, particularly through the impact that processed photos on social media platforms can have on them. At the policy level, some basic rights of adolescents, especially girls, including sexual and reproductive health information rights, are not afforded in Jordan, leaving them vulnerable to misinformation and uninformed about the physical and cognitive changes that occur during puberty.

Among children, Syrian nationals had the highest rates of anxiety and depression symptoms across all subscales and total scales. These high rates may be attributed to the numerous traumatic and stressful events they have experienced since the beginning of the Syrian civil war, such as displacement, separation from family members, and acceptance into the host society. These rates continue to be high in adolescence for Syrians but in conjunction with higher rates for Palestinian refu

留言 (0)