A total of 37 cancer patients were interviewed, representing five out of the 12 districts in Meghalaya: East Khasi Hills, West Khasi Hills, East Jaiñtia Hills, West Jaiñtia Hills and Ri Bhoi. Demographic characteristics of the 37 respondents interviewed are shown in Table. There were also 12 caregivers who participated in the study, all, but one, were female. The mean (SD) age of the caregivers was 43.3 (15.8) yr. The HCPs included two male and one female oncologist and two female nurses.

Table. Demographic characteristics of cancer participants

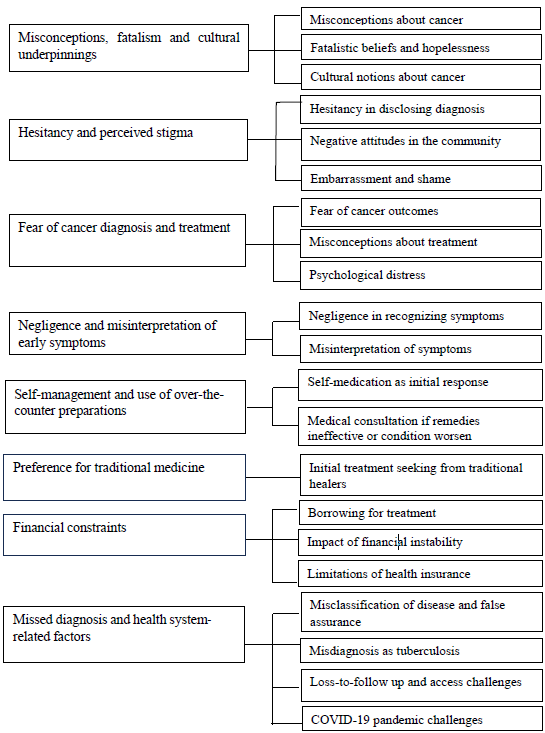

Male (n=17) Female (n=20) Total Age in yr; mean (±SD) 56.2 (±10.2) 51 (±10.3) Types of cancer Oesophageal 8 1 9 Oral 4 3 7 Lung 5 1 6 Breast 0 8 8 Cervical NA 7 7 Disease stage known 5 9 14 Stage I and II 4 2 6 Stage III and IV 1 7 8 Time to diagnosis known 10 12 22 >3 months 5 9 14 <3 months 5 3 8 First point of consultation 17 20 Western medicine 10 17 27 Traditional medicine 7 3 10 Factors affecting health seeking behaviour for cancerThe findings from the three participant groups on factors contributing to the delay in seeking cancer health are presented under nine themes (Figure), which are described below. An anonymized unique identifier of each participant where ‘P’stands for cancer patient, ‘CG’ for caregiver and ‘HCP’for health care providers was given.

Export to PPT

Misconceptions, fatalism and cultural underpinningsMisconceptions among 15 cancer respondents about the causes of cancer emerged as one of the major barriers to timely health seeking, both for males and females. Although 12 acknowledged and attributed their disease to habits such as alcohol consumption, smoking and betelnut chewing, a small proportion of the respondents (7/37) indulging in such habits did not believe that tobacco and betelnut chewing were risk-factors that potentially contributed to their disease. This risk-denial among these individuals was, according to them, based on their observation that not all tobacco smokers and betelnut consumers get cancer.

Beliefs related to the causes of cancer were often attributed to fate or bad luck. Fatalistic beliefs about cancer outcomes were narrated by some of the patients (10/37) as a result of which there was a sense of hopelessness and doubts regarding cancer treatment. Caregivers also mentioned that they had observed this fatalistic attitude in patients they cared for.

‘I really don’t know much about that, Kong [adult woman]. Perhaps it’s my fate that it has been written that I should suffer from this disease, so that is all. If any man is destined to suffer from this disease, there is no escape and it is not because of any other reason.’ (P-19, 65 yr, male)

HCPs and caregivers also highlighted prevalent cultural concepts in the community regarding the cause of cancers, such as the concept of bih (Khasi word). Bih is not an easily translatable word; its literal translation could be ‘poison’, but here, it does not really represent poison in the literal sense; rather it represents a concept in Khasi which embodies a situation associated with an illness acquired after a person has come in contact with or eaten food with/of a person with bad intent. Likewise, participants used words that represent an insect or germ within, but not necessarily as it is understood in a biomedical sense. Another term used was the word skai, likely equivalent to the evil eye in English, which is believed among Khasis to render one vulnerable to illness.

This ‘skai’ is fairly prevalent; individuals will give you this ‘skai’ just by looking at you. I’m not sure how to explain it, but that ‘skai’ is really common here, and we believe in it. For example, once a woman gives birth, they advise her not to display her baby to others since she would receive ‘skai’ from others. We heard/learnt of this from our elders’ (HCP-004)

Hesitancy and perceived stigmaWhile a cancer diagnosis was often disclosed to family members by the patient, there was hesitancy in disclosing the diagnosis among a few other participants (6/37), as they were ‘uncomfortable’ to talk about their diagnosis with friends and neighbours. Some caregivers also believed that disclosure could bring bad luck; hence they were hesitant.

‘Besides our own close relatives, I personally never tell. Because why would I tell right? Considering that, if I myself tell them, then its just like, it will bring bad luck. That is why I never want to tell others’(CG, 56 yr, female)

Some caregivers reported that negative attitudes within the community exacerbated the burden on the affected families. The concept of ‘kren jemdaw,’ referring to speaking negatively about a person, is believed to render them susceptible to illness or misfortune.

‘He used to share it with his own friends too. But he felt angry because there are other people who would be kren jemdaw. He would get angry with such people’ (CG, 29 yr, female)

Embarrassment and a sense of shame contributed to perceived stigma, depending on the body parts affected.. For example, female patients suffering from breast and cervical cancers expressed these feelings. This was corroborated by caregivers and HCPs.

‘Long time back… when the surgery was done, since her whole breast had been cut, she was embarrassed that people would notice’ (CG, 52 yr, male)

‘In case of breast and cervical cancer many patients feel shy to come seek help as they think it is shameful to tell others that they have problems in those areas. So, for so many years they try to self-manage and when the condition advances, they have no other way out than to show the doctors’(HCP-002)

Fear of cancer diagnosis and treatmentFear surrounding cancer diagnosis and treatment among patients was predominantly expressed by the HCPs, who noted that many patients viewed cancer as incurable and synonymous with the end of life.

Misconceptions about cancer treatment, such as radiation and surgery, were also identified as the underlying cause of fear associated with seeking cancer treatment.

‘Patients think that radiation means they will be roasted (syang) in that machine or that they have to burn themselves in that machine but it is not like that. Radiation is also just like any other test like x-ray and all’ (HCP-003)

Such fear was commonly seen among the cervical and breast cancer patient respondents, who often harboured fearful and fatalistic beliefs. The fear of cancer diagnosis and treatment were also cited as reasons for incomplete therapy and loss to follow up by the HCPs. Cancer-induced psychological distress, caused by concern over the fate of dependent family members (especially children), family responsibilities, and inability to meet treatment costs, was also expressed by the patient respondents (11/37).

Negligence and misinterpretation of early symptomsSixteen patient respondents attributed the delay in treatment seeking to their own negligence, not recognizing their early symptoms as serious. They interpreted their symptoms as harmless and mild, often equating them to ailments such as cold, gastritis, ulcers, etc. Oral cancer patient respondents often attributed their mouth ulcers to common cold or transient mouth ulcers which they perceived to be caused by unwashed betel leaves.

Female cervical cancer patients aged over 40 yr often interpreted their symptoms as post-menopausal changes. There appeared to be a phase when they were constantly engaging in an internal debate on the seriousness of the issue and whether or not they needed to seek care. This ‘internal dialogue’ phase emerged as a key barrier to taking the first step in the health-seeking trajectory.

‘As days passed the flow was increasing, so later the flow stopped and the white discharges started. So, I thought to myself that since I have crossed 50 yr, it may be normal. So, it continued like that…’ (P-17, 54 yr, female)

Self-management and use of over-the-counter preparationsSelf-medication was the primary response for managing the first symptoms in many patients (11/37), particularly among females (9/11). Medical consultation was sought only if self-remedies proved ineffective or if the condition worsened.

‘I applied ointment that I obtained from the pharmacy because I assumed it was an ulcer, and I never expected to acquire this kind of condition; yes, I went to the pharmacy and bought mouth ulcer medication’ (P-18, 42 yr female)

The tendency of self-medication among the patient respondents was also observed among the caregiver respondents (3/12), as they were also under the assumption that the early symptoms experienced by the patients were due to common ailments.

‘From the beginning we have been taking medicines from the pharmacy because we thought it was just a headache and that he would recover in only two or three days. He wasn’t very sick because he was just sneezing like that’ (CG,26 yr, female)

The above observations were further corroborated by HCPs, who mentioned that self-management of symptoms, by taking painkillers for pain, was common among cancer patients who neglected their health condition for a long time especially when there was symptomatic relief with over-the-counter preparations.

Preference for traditional medicineClose to one-third (10/37) of the patient respondents first sought treatment from traditional healers. This preference for traditional medicine was more prevalent among males than in females. Traditional medicine was preferred as it was affordable, and accessible and widely used for various ailments.

‘I didn’t really pay much attention to it, so I went for traditional medicine since I have been used to taking such medicines’ (P, 38 yr, female)

Moreover, patients frequently reported positive experiences with traditional medicine for past illnesses; HCPs echoed similar observations. Additionally, recommendations from friends and neighbours also influenced patients to seek traditional medicine.

‘Yes, for cough and all I used to take that traditional medicine and it is very good for cough’ (P-03, 38 yr, female)

Preference for traditional healers as the first point of contact was also reported by some of the caregivers (3/12). A couple of patients (2/12) reported taking treatment from a traditional healer along with their modern medicine (biomedicine) provided from hospitals.

Financial constraintsFinancial constraints affected the decision to seek treatment among one fourth (10/37) of the patient respondents. Patients had to borrow from friends and neighbours to cover the costs of treatment.

‘As the doctor advised, they sent me here at the appropriate time; however, I had to wait for a while because I didn’t have enough money to pay for the treatment. I had to arrange for the money and waited until I received it from my friends’ (P-019, 54 yr, male)

Some patients who initially could afford treatment at private hospitals, found themselves financially constrained, leading them to opt for subsidized cancer chemotherapy available at the government hospitals. Financial instability also compelled several patients to compromise on treatment decisions. The caregivers also highlighted that financial instability limited the patient’s choice to more affordable/subsidized services, offered by the government hospitals.

The HCP pointed out that financial constraints often led the patients to discontinue treatment.

‘Socio-economic constraint is a big reason that most of the people are unable to seek treatment. There are many who stop treatment because of lack of money. Patients in the far away rural areas need to pay a lot for their travel and food; therefore follow ups and many visits for treatment is not affordable to them’ (HCP-002)

Financial support through the Meghalaya Health Insurance Scheme (MHIS), which is a government-sponsored universal health insurance scheme for the residents of Meghalaya, was availed by nine patients. Patient respondents, however, expressed that MHIS was of little assistance, as it did not cover all the treatment costs. Among the caregivers, only five of 12 participants reported that the patients they cared for availed the MHIS, which helped cover small medical expenses (such as buying medicines), but was of little relief to their overall financial distress.

Missed diagnosis and health system-related factorsSome patient respondents (8/37) identified health system-related factors as the causes of delay in their cancer health seeking path. These included misclassifications of the disease as common ailments (such as gastritis) and false assurance from the treating physician/s that their signs and symptoms were harmless. A breast cancer patient explained that she left the swelling untreated based on the physician’s assurance that it was nothing of concern, only to be diagnosed with stage III cancer months later. Another patient said,

‘I don’t know sister, whether I sought treatment on time or have delayed. I can’t explain anymore, because from my side I went for treatment at the earliest, but the doctors themselves said it was gastritis, what else could I do?’ (P-022, 49 yr, female)

Misdiagnosis of the disease as tuberculosis and the prolonged antitubercular treatment thereof were also attributed as a factor responsible for the delay in treatment initiation among the lung cancer patients (2/6).

‘At first, the doctors said that it was TB so they took care of it. I took TB medications, an enormous amount of them I took every day for 4-5 months’ (P, 56 yr, female).

Loss-to-follow up of suspected cases referred from the peripheral health centres was common. As patients coming to the Civil Hospital Shillong hail from remote villages, the access to this hospital, or even the district hospitals, is challenging due to the geographical terrain and poor road conditions leading to increased transportation costs which, in turn, result in patients not visiting hospitals for follow up.

‘For suspected cases, we will make sure that they are referred. But whether they go or not, we cannot say anything. Because some of the patients, once they know about their suspected diagnosis, they give up as it is quite a distance to go to the city …’ (HCP-005, HCP)

Besides transportation difficulties, the HCPs stated long waiting hours, unavailability of physicians and delay in reporting as some of the other perceived reasons for the delay in initiating treatment.

Among the health system-related factors, the lack of cancer diagnosis and treatment facilities often compelled HCPs to refer patients to hospitals outside the state for treatment, which may be unaffordable. Absence of a professional counsellor in the hospital to address the psychological needs of the cancer patients, was also identified it as a gap in healthcare provision.

Several patients explained that the COVID-19 pandemic was one of the causes for delay in seeking healthcare, as they encountered difficulty in reaching the hospitals due to the travel restrictions imposed during the lockdown. Inadequate manpower during the pandemic also posed major challenges for the HCPs at the hospitals. A drastic decline in cancer patients visiting the hospital for follow up, during the pandemic, was highlighted by the HCPs.

Support and coping mechanismsDespite enduring considerable uncertainty and challenges during their cancer treatment, patients and their families relied on various support and coping mechanisms. Religious faith emerged as the predominant facilitator in cancer health seeking among half of patient respondents (18/37) and their caregivers.

‘At first, we told at home, then to the other faithful; we prayed together. After the prayer we felt good and believed that God will show wonders in our lives’ (CG, 53 yr, female)

Almost all patients received emotional support from their families during their cancer treatment, fostering hope. Family support was cited as crucial to the health-seeking behaviour of seven patients, influencing their decision to seek medical consultation for symptoms and adhere to medical treatment.

留言 (0)