A death certificate (DC) is a medico-legal record stating the medical cause, time, place and manner of an individual’s death. The medical certification of cause of death (MCCD) provides epidemiological information for developing cause-specific mortalities and disease trends. Policymakers require this information to prioritize health and research resources distribution, and monitor the impact of health programmes1,2. The effects of DCs on families, learning programmes, health-related policies, monitoring, research and indicators are substantial3,4.

Geographical coverage of mortality registration ranges from nearly 100 per cent in Europe to ∼50 per cent in Asia-Pacific, and less than 10 per cent in Africa5. In India, only 20 per cent of deaths are registered, and 50-60 per cent of the registrations are incorrect4,6. The time series data on MCCD in India (1991-2015) demonstrates a significant but gradual increase in the frequency of medically certified cases. During this period, the proportion of registered deaths that were medically certified fluctuated between 12.7 to 22 per cent. In addition, since all deaths do not occur in hospitals, hospital-based mortality statistics cannot reflect the actual scenario. Hence, the verbal autopsy is used in the sample registration system7.

It is not uncommon to find MCCD having errors due to illegible handwriting, incompletely filled certificates, incorrect medical causes and manners of death. Despite poor medical certification status in India, less importance is given to teaching death certification in undergraduate medical courses8. However, several studies have reported certification errors in MCCD from different parts of India. A comprehensive review of all these published studies that can report the burden and pattern of certification errors is still lacking. With this background, we aimed to describe the status of MCCD in India regarding the proportion and types of certification errors reported in previous Indian studies and the methodology adopted by these studies for identifying errors in death certification.

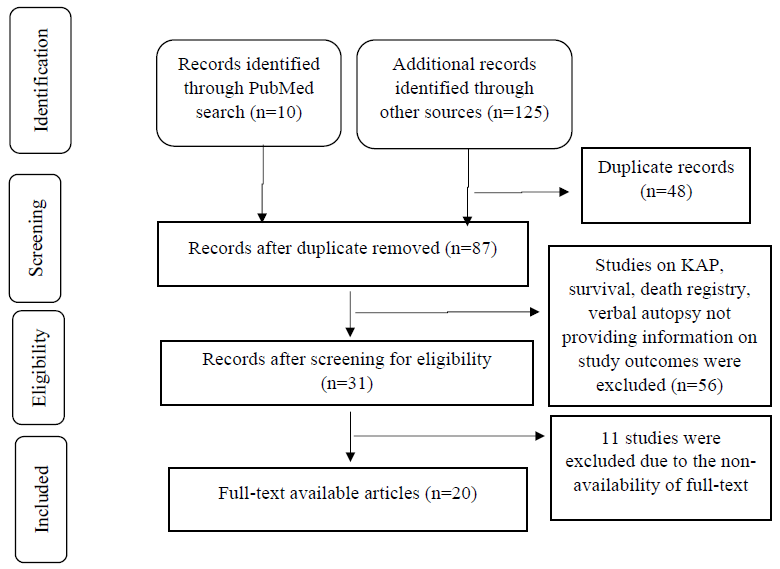

Material & Methods Literature search methodologyWe conducted a systematic inquiry in four databases, namely PubMed, ProQuest, Google Scholar and EBSCO, with the MeSH and free text words such as ‘cause of death’ or ‘medical cause of death certificate’ or ‘death registration’ or ‘death audit’ or ‘death certification’ or ‘hospital deaths’ or ‘vital statistics’ or ‘quality of death certificates’ or ‘validation of cause of death’ or ‘death certificate’ and ‘India’, published between December 31, 1998 and December 31, 2020. We did not attempt to search for any unpublished data. The bibliography list of all included studies was also cross-referenced to ensure a full literature search. Authors of the articles for which full text was not accessible online were requested, and the full text thus obtained was included in this inquiry.

Eligibility criteria Criteria for inclusionThis study included published investigations (in English) conducted on the cause of death (COD) certification in India and reported the frequency of certification errors.

Criteria for exclusionMortality studies from India that were not evaluating death certification errors were excluded such as knowledge, attitude and practice studies of the certifying physicians9, survival studies10, disease registry11, verbal autopsy-based studies12, 14etc. Studies for which full text was not accessible and news or media reports that were not published in scientific journals were also excluded (Figure).

Export to PPT

Article selection and data extractionArticles/titles/abstracts with the keywords were screened by two independent investigators based on the defined eligibility criteria. Two researchers independently screened all headings, abstracts and full-text documents and resolved disagreements by consensus or consulting with the third researcher. Subsequently, information for the following was abstracted from the included studies: (i) place of study, (ii) study design, (iii) number of death certificates assessed, (iv) types and percentage of errors in MCCD, (v) completeness of the death certificate, (vi) methodologies adopted in the audit of death certificates.

Outcome measures Definitions of cause of deathThe World Health Organization (WHO) defines the cause of death (COD) in relation to writing MCCD15. The underlying cause of death (UCOD) is ‘the disease or the injury which initiated the train of morbid events leading directly to the death or the circumstances of the accident or violence that produced the fatal injury’15. Immediate cause of death (ICOD) is ‘disease or condition directly leading to death’15. Antecedent cause of death is ‘morbid conditions, if any, giving rise to the immediate cause of death’15. Contributory conditions are ‘all other diseases or conditions believed to have unfavourably influenced the course of the morbid process and thus contributed to the fatal outcome but which were not related to the disease or the condition directly causing death’15. Disease-related symptoms and modes of dying, such as cardiac and respiratory arrest, are not included in these definitions15.

The outcome measure was the proportion of certification errors reported in the included studies, which were categorized as major and minor based on the method of audit described by Myers and Farquhar16. Major errors were the errors that could influence the correct identification of the underlying cause of death, such as: (i) the mechanism of death or non-specific condition mentioned as an underlying cause of death, (ii) improper sequence of events leading to death, (iii) mentioning two or more causally unrelated, aetiology-specific diseases (competing causes) in part I of MCCD, and (iv) based on the clinical review of medical records it was found that the COD was not acceptable. Minor errors were: (i) use of abbreviations, (ii) absence of time-intervals in parts I and II of the MCCD, (iii) technical or clerical errors in the form of wrong or missing personal identifiers (age, gender and place of residence), incomplete certifying physician details, illegible handwriting and incomplete or wrong clerical details in the MCCD. Many studies reported incomplete information in part I and/or part II of the MCCDs. We categorized this as a major error (Table I)16.

Table I. Definition of major and minor errors in death certificates

Type of error Definition Major errors Mechanism of death listed without an underlying cause A mechanism or nonspecific condition is listed as the underlying cause of death Improper sequencing The sequence of events does not make sense; the underlying cause of death is not listed on the lowest completed line of part I Competing causes Two or more causally unrelated, etiologically specific diseases listed in part I Unacceptable cause Wrong cause of death based on the review of clinical records or any one of the above errors (either alone or in combination) Incomplete MCCD MCCD information in part I and/or II is incomplete Minor errors Abbreviations Abbreviations used to identify diseases Absence of time intervals No time intervals are listed in parts I or II Mechanism of death followed by a legitimate underlying cause of death Use of a mechanism but qualified by an etiologically specific cause of death Technical or clerical errors Mentioning wrong personal identifiers (such as age, gender, & place of residence), incomplete certifying physician details, illegible handwriting, and incomplete or wrong clerical details in the MCCD Data analysisData collected during the review was entered and analyzed using Microsoft Excel. Descriptive statistics in frequencies and proportions were reported for the outcome variables.

ResultsA total of 135 studies were screened, and 20 studies6,8,17, 34, were included in the review based on the eligibility criteria. Studies for which the full text was not available (n=11) were excluded (Figure). The abstracted information from the included studies is mentioned in Table II.

Table II. Characteristics of the reviewed studies

Author/yr/

place of study

Study design Sample size Key findings Type of study setting & qualifications of the certifying doctorsPatel et al6 (2017);

Madhya Pradesh

Observational 53 death certificates Not a single certificate was error-free. The immediate, antecedent, & underlying cause of death were inaccurate in 79.2, 75.5, & 67.9% of DCs, respectively Tertiary teaching medical college. Physicians’ qualification NA, Ward setting details NAPandya et al8 (2009);

Gujarat

Interventional: The frequency of major & minor errors in death certificates was examined before & after conducting 3 workshops, each of 90 min, for the post-graduate residents 198 death certificates Significant decrease in major certification errors post-intervention Tertiary teaching hospital. All clinical residents. Qualification & ward settings details NAPrakash et al17 (2010);

Delhi

Observational 259 death certificates 32% had an incorrect cause of death. Among these, 27% mentioned the mode of dying as COD Referral oncology center with surgical, radiation, medical, & palliative oncology doctors. Qualification & ward settings details NAAgarwal et al18 (2010);

Gujarat

Observational 296 death certificates In 86% of DCs, the immediate cause of death was mentioned as a mode of death Tertiary teaching hospital. Qualification & ward settings details NAPatel et al19 (2011);

Gujarat

Observational 45 death certificates Not a single certificate was error-free. Major errors in 57.5% DCs. Minor errors in 92.5% of DCs. 80% of DCs reported mode of death as the immediate cause of death Tertiary teaching hospital. Casualty, Intensive care unit, medical ward, & others (not specified), Qualification detail NAShah et al20 (2012);

Gujarat

Observational 3212 death certificates Major errors: The accuracy of immediate cause, antecedent cause, & underlying cause was 44, 55, & 69.9%, respectively. Only 1.2% of the certificates were accurate Tertiary health institute. Qualifications & ward settings details NALanjewar et al21 (2013);

Not mentioned

Observational 229 death certificates 58% of DCs were completely filled. Out of completely filled certificates, 82.7% had an accurate COD Medicine & allied, surgery & allied, pediatrics, forensic medicine, obstetrics, & gynecology departments. Qualifications details NADash et al22 (2014);

Odisha

Observational 151 death certificates Major errors : The antecedent cause was filled in 27%, & the underlying cause was filled in only 0.8%. Most MCCD forms were incomplete (96.19%). Gender was missing in 45.7% Tertiary care teaching institute. Qualifications & ward settings details NAAzim et al23 (2014);

Uttar Pradesh

Interventional; pre & post-intervention audit conducted for reporting death certification errors. The intervention included an interactive educational programme for residents training for super speciality 150 death certificates Significant decrease in major certification errors post-intervention Tertiary care teaching institute. Resident doctors are undergoing subspecialty training in Critical Care Medicine. Ward setting details NAGanasva et al24 (2015);

Gujarat

Observational 1942 death certificates Immediate, antecedent, & underlying causes were reported in 95.9, 27, & 0.8% of the DC, respectively. Only 1.1% were completely filled Private practitioners from 12 wards of Municipal Corporation. Qualifications & ward settings details NAPokale et al25 (2016);

Maharashtra

Observational 98 death certificates Two major errors were combined in 35.6% of DCs, three major errors in 8.6%, & at least one minor error in 99.3% of DCs. The most common error was the absence of a time interval (98.9%) Tertiary care hospital. The majority are issued by the medicine department. Qualifications details NAAhir et al26 (2018);

Gujarat

Observational 523 death certificates Only 20.1, 26.8, & 28.9% of MCCD forms were accurate in determining the immediate cause, antecedent cause, & UCOD Tertiary care teaching hospital. Qualifications & ward settings details NAUplap et al27 (2019);

Maharashtra

Observational 410 death certificates All DCs were incomplete & inaccurate. Mode of dying mentioned as immediate or antecedent cause of death in 86 & 41%, respectively. Multiple causes in 56% DCs Tertiary care hospital. Resident medical officers. Qualifications & ward settings details NAPatil et al28 (2019);

Maharashtra

Observational 278 death certificates Completeness for the immediate, antecedent, & underlying cause of death was 99.7, 98.3, & 88%, respectively. Sequencing errors in 64.7%, Unacceptable COD in 37.8% Tertiary care teaching hospital. Qualifications & ward settings details NASudharshan et al29 (2019);

Tamil Nadu

Interventional; pre- & post-assessment of accuracy in writing MCCD for case-based scenarios given before & after a lecture on writing MCCD. 80 physicians Significant decrease in major & minor certification errors post-intervention Teaching hospital. Teaching faculty, post-graduates, junior residents, & interns (who have completed medicine & surgery postings). Ward setting not applicableRaje30 (2011);

Maharashtra

Observational 353 death certificates 19% of deaths were in the incorrect sequence. Multiple COD: 25%. Use of abbreviations: 68%. Illegible name & signature of certifying physician: 85% The teaching hospital attached a Medical College. Qualifications & ward settings details NASheikh et al31 (2012);

Telangana

Observational 156 death certificates Modes of death reported as COD in 37.8 certificates General Hospital. Medical doctors. Qualifications & ward settings details NAGupta et al32 (2013);

Chandigarh

Observational 1251 death certificates Any error: 97.1% vs. 73.3% (P<0.05). Any major error: 61.9% vs. 45.0% (P<0.05). Any minor error: 96.5% vs. 92.6 (P<0.05) Tertiary pediatric hospital. Qualifications details NASrinivasulu et al33 (2014);

Andhra Pradesh

Observational 110 death certificates Not a single form was error-free 47% reported major errors, 21% minor errors Rural medical college hospital. Qualifications & ward settings details NAJain et al34 (2015);

Gujrat

Observational 7392 death certificates Only 2% of certificates were completely filled. Modes of death were COD in 82.2%. Completeness for the immediate, antecedent, & underlying cause was 95.56, 66.67, & 40%, respectively Municipal Corporation’s Registrar Birth & Death office. The doctors’ qualifications are not accessible. Ward setting details NA Characteristics of the studies includedThe included studies assessed a total of 17,106 DCs and the number of DCs covered in each study was in the range of 45 DCs19 to 7392 DCs34. Most of these studies were conducted in Gujarat State (7 studies)8,18, 20,24,26,34 followed by Maharashtra (4 studies)25,27,28,30 and the rest were from Delhi17, Chandigarh32, Uttar Pradesh23, Odisha22, Madhya Pradesh6, Andhra Pradesh33, Telangana31 and Tamil Nadu.29 Majority of the studies were observational (17 studies)6,17, 22,24, 28,30, 34 and three were interventional8,23,29. The interventional studies conducted death certification training for resident doctors and teaching faculty and assessed the effect on the post-intervention quality of death certification. All interventional studies reported a reduction in certification errors post-intervention. Interventions were in the form of seminars, training sessions and participatory workshops. One study29 provided case-based scenarios before and after intervention in the form of training on death certification and compared the certification errors for the case scenarios; these studies were conducted at tertiary care teaching hospitals6,8,18, 20, 22,23,25, 30,33 (Table II).

Major certification errorsThe included studies reported substantial errors in the UCOD (8.5-99.2%), the ICOD (0.3-79.9%) and the chain or sequence of events preceding death (12-64.7%). Modes or mechanisms of death, such as cardiopulmonary arrest, were incorrectly mentioned as the COD in the range of 8.9-86 per cent. An unacceptable COD was reported in the range of 13.2-92.9 per cent (Table III)20, 36. Out of the 12 studies that evaluated the completeness of the DC, all but one reported a very high proportion of incompleteness in DCs (Table III)20, 36.

Table III. Description of type of errors in the medical certification of cause of death

Category Number of studies describing the certification error Proportion of errors (%) Minor certification errors Wrong personal identifiers21,24,25,29,30,31,32 7 0.3 - 100 Incomplete certifying physician details20,23,24,27,28,32,35 7 0.5 - 64.2 Use of abbreviations21,24,25,29,30,31,32 7 29.3 - 98 Illegible handwriting21,24,30 3 15 - 52.3 Absence of time intervals8,10,20, 21,22,24,25,26,27,29,30,31,34,35 14 62.3-99.5 Incomplete/wrong clerical details in the MCCD22,29,30,32 4 2.7 - 100 Major certification errors Incorrect underlying cause of death8, 10,21,24,25,26,29,34,35 9 8.5 - 99.2 Incorrect immediate cause of death8,20,24,26,29,30,32,35 8 0.3 - 79.9 Incorrect chain/sequence of events8,10,21,25,32,34 6 12 - 64.7 Modes of dying as a cause of death8,21,22,33,35 5 8.9 - 86 Others (not acceptable cause of death)10,25,30 3 13.2 - 92.9 Incompleteness of MCCD in part I & part II of MCCD21,22, 25,26,27,29,30,31,32,34,35,36 12 21-100 Minor certification errorsMissing time intervals for COD was the most reported certification error in the included studies (62.3-99.5%). Other reported errors were wrong personal identification (0.3-100%), incomplete certifying physician details (0.5-64.2%), abbreviations (29.3-98%) and illegible handwriting (15.0-52.3%) (Table III)20, 36.

Patterns of reporting certification errorsDeath certification audit studies have been reported from only selected States in India, such as Gujarat, Maharashtra, Uttar Pradesh, Odisha, Tamil Nadu, Andhra Pradesh, Telangana, Delhi and Chandigarh. Published data for death certification errors was lacking from many other States.

We found that the pattern of reporting death certification errors was not uniform. The outcomes for reporting certification errors varied in the included studies (Tables II and III). We reviewed the included articles for their adopted methodologies to audit death certification. Ten studies described the standardized definitions or guidelines used for reporting certification errors6,8,20,21,

留言 (0)