Cancer is one of the major public health issues worldwide and is the leading cause of death in many countries. According to the latest data published in 2023, approximately 1,958,310 new cancer cases were present in the United States (1). Moreover, due to the high mortality rate and low cure rate of cancer, it has brought heavy economic burden to individuals, families, and society. Therefore, the prevention and treatment of tumors were urgent to further decrease the morbidity and mortality rates. Surgery, radiotherapy, and chemotherapy are three traditional treatment strategies for cancer, but the treatment outcome was still dismal in some patients (1, 2). In the recent years, emerging treatment methods were developed, such as Chimeric antigen receptor (CAR)-T cell therapy and immune-checkpoint inhibitors, which were considered as the fourth treatment mode following the traditional therapy. At present, immunotherapy has been approved for clinical use, mainly including programmed death receptor 1 (PD-1) inhibitors and CAR-T cell therapy, both of which have achieved excellent results in some advanced stage malignant tumors (3–6). However, the efficacy of PD-1 inhibitor was limited in some patients with cancer (7), and the efficacy needs to be further improved.

Tumor microenvironment was considered to be a key factor affecting tumor progression, metastasis, and treatment results (8, 9). Exploring the tumor microenvironment is the cornerstone of improving response rate and developing new cancer immunotherapy strategies. In addition, macrophage was reported to be one of the most important immune cells in the tumor microenvironment (9). Based on the function of phagocytosis, macrophage can eliminate tumor cells at an early stage, but, under the stimulation of the stimulating factors in tumor microenvironment, they gradually transform into tumor-related macrophages with M2 phenotype and promote tumor growth and metastasis by inhibiting immunity, inducing angiogenesis and supporting cancer stem cells (10). To sum up, it is of great significance to explore in great depth the role of macrophages in the tumor microenvironment, and targeting macrophages may a promising anti-tumor strategy in the future.

2 Origin, polarization, and function of macrophagesMacrophages originate from the monocytes in the circulation, and a substantial heterogeneity was observed among each macrophage population (11). According to the phenotype and function, macrophages can be divided into two types: classically activated macrophages (M1 macrophages) and alternatively activated macrophages (M2 macrophages) (12). M0 macrophage could differentiate into M1 macrophage under the stimulation of lipopolysaccharide and interferon-γ (IFN-γ), whereas it differentiates into M2 macrophage with the stimulation of Interleukin (IL)-4, IL-10, and IL-13 (13). M1 macrophages could produce multiple cytotoxics such as nitric oxide and reactive oxygen species and thereby activate the function of multiple immune cells and reduce microbial activity, which ultimately eliminate microbial infection (14). Meanwhile, a variety of cytokines were produced by M1 macrophages, including tumor necrosis factor–α (TNF-α), growth inhibitors, and anti-angiogenic factors, which could inhibit cancer progression (14). On the contrary, M2 macrophages often function as anti-inflammation factor by reducing the inflammation response, promoting tissue repair and remodeling the immune system (10, 14). Tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs) were mainly considered to be M2 type in the tumor microenvironment, which could promote tumor growth, invasion, and metastasis.

3 Macrophages in the TME promote tumor progressionMacrophages are involved in different stages of tumor development. In the early stage, tumor cells release cytokines and exosomes and attract macrophages and other inflammatory cells into the tumor stroma, where macrophages promote tumor growth, migration, and metastasis (10). As a key component of the tumor microenvironment, macrophages can produce anti-tumor effect and cause tumor necrosis with powerful swallowing phagocytosis (15), but some studies have shown that TAM is an important driving factor of tumor progression. In the formed tumors, TAM promotes the growth and proliferation of cancer cells, angiogenesis, and lymphangiogenesis and inhibits the immune response of effector T cells (16).

TAM is considered as a proinflammatory and anti-tumor phenotype (M1 type) in the early stage of lung cancer and gradually displays an anti-inflammatory and tumor-promoting phenotype in the process of cancer progression (10). TAM could promote tumor development through immune regulation and non-immune processes (17–19). For example, TAM secretes a large number of pro-angiogenic factors such as vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) to promote tumor angiogenesis and metastasis (20).

In the tumor microenvironment, macrophages account for half of the total number of tumor cells and are mainly M2 phenotype. The quantity of macrophages in the tumor microenvironment is associated with tumor micro-vessels and is negatively correlated with the survival outcome in patients with Non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) (21, 22). In the recent years, a growing body of research has revealed the TAM multifaceted regulation of the co-evolving cancer ecosystem based on next-generation technologies and single-cell sequencing technology (12, 22). Therefore, this section mainly introduces the function and mechanism of TAM in tumor.

3.1 Anti-tumor effect of M1 type TAMInhibition of the anti-tumor immunity was reported be the main pathogenicity mechanism of TAM. TAM could downregulate the release of immunostimulatory factor IL-12, which can trigger the tumor killing effect of natural killer (NK) cells and cytotoxic CD4+ T cells (23). In addition, many immunosuppressive factors produced by TAM could also mediate cancer development, such as IL-10, transforming growth factor–β and prostaglandin E2 (10, 24, 25).

TAM can also directly inhibit the function of T cells through specific enzyme activities, such as arginase 1 (ARG1), which is a hydrolase that controls the catabolism of L-arginine. ARG1 is induced by multiple signaling pathways mediated by IL-4, IL-10, and hypoxia and affects T-cell function by limiting the activity of semi essential amino acid L-arginine (25). TAM may also promote T-cell apoptosis by inhibiting the expression of programmed cell death ligand 1 (PD-L1) and B7 homolog 1 on T cells (12, 25).

3.2 The function of M2 type TAM in promoting tumor developmentThe function of M2 macrophages in promoting tumor development depends on the proinflammatory cytokines, such as TNF-α, IL-6, and IL-11, which can activate nuclear factor–κB (NF-κB) and signal transduction and activator of transcription 3 (STAT3) pathway in cancer cells (10, 12, 13, 18, 25). In addition, M2 TAM promoted tumor progression by promoting angiogenesis and lymphangiogenesis by enhancing the expression of VEGF-A and VEGF-C (18, 20, 25).

4 Macrophages and anti–PD-1/PD-L1 immunotherapy4.1 Effect of TAMs on PD-1/PD-L1 expressionPD-1/PD-L1 pathway was abnormally activated in various cancers (6, 26) and anti–PD-1/PD-L1 immunotherapy has been widely used or tried in clinical trials in many solid tumors, such as lung cancer, advanced metastatic melanoma, esophagus cancer, and colorectal cancer (27, 28). However, the efficacy of PD-1 inhibitors was still dismal in some patients with high expression of PD-L1, and the concrete mechanisms remain largely unknown.

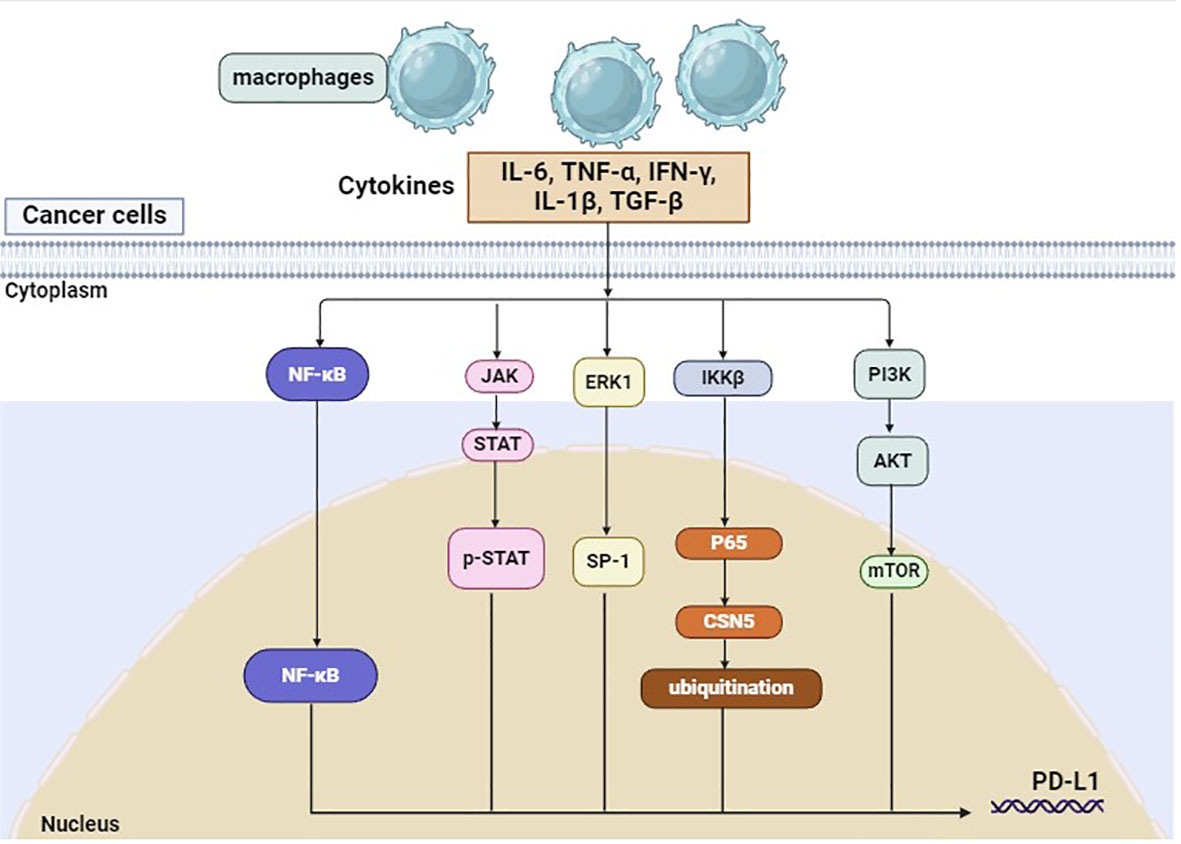

Previous studies have demonstrated that TAMs can regulate the expression of PD-1/PD-L1 through activation of different signaling pathways (Figure 1), which, in turn, affects the efficacy of PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors. CD163+ TAMs in the tumor microenvironment are reported to be positively correlated to PD-L1 expression in various cancers, including pancreatic cancer and liver cancer. Multiple cytokines released by TAM, including IL-6 and TNF-α, can upregulate PD-L1 expression by activating Janus kinase (JAK)/STAT3, phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K)/AKT, NF-κB, or Extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK) 1 and 2 signaling pathways (29, 30). In addition, the PD-L1 protein expression could also be upregulated by TNF-α through post-translational regulation (29).

Figure 1 PD-L1 on tumor cells can be regulated by macrophages.

4.2 TAMs and anti–PD-1 resistanceIn addition to the PD-L1 expression on tumor cells, the tumor microenvironment was also a key factor associated with anti–PD-1 resistance. As mentioned above, cytokines released by TAMs could regulate PD-L1 protein expression, which was reported to be an important predictor for anti–PD≥1/PD≥L1 therapy. In the recent years, multiple immune cells were identified in TME and the cancer ecosystem evolved over time, which play a complex role in cancer development (31, 32). The interaction between macrophages and other immune cells was explored and was demonstrated to be correlated to the response of immunotherapy (31). Single-cell and spatial analysis showed that interaction between FAP+ fibroblasts and SPP1+ macrophages could promote the formation of immune-excluded desmoplasic structure and restrict the T-cell infiltration, which reduces the efficacy of immunotherapy (31). In triple-negative breast cancer, high levels of CXCL13+ T cells are associated with the proinflammatory features of macrophages and can predict clinical benefit of checkpoint inhibitors (32).

Exosomes were small extracellular vesicles, which play a crucial role in various cell activities in cancer. Recent studies have reported that macrophage-derived exosomes could promote the formation of a pre-metastatic niche, which facilitates tumor growth and metastasis. M2 macrophage–derived EVs can drive anti–PD≥1/PD≥L1 therapy resistance and promote the expression of drug resistant genes in tumor cells or affect the immune cell spectrum in TME (33, 34). Therefore, the interaction between TAMs and TME may contribute to anti–PD≥1 therapy resistance in cancer, providing a theoretical basis for the combination use of targeting macrophages and anti–PD≥1/PD≥L1 therapy.

4.3 Effect of anti–PD-1/PD-L1 therapy on macrophagesPrevious studies have shown that PD-1 inhibitors have an impact on TME in various cancers (35). In non–small cell lung cancer, single-cell RNA sequencing demonstrated that the tumor microenvironment was remodeled after neoadjuvant PD-1 blockade combined with chemotherapy, and TAMs were transformed into a neutral type instead of an anti-tumor phenotype (36). Furthermore, anti–PD-L1 therapy can inhibit tumor growth by reducing PD-L1 expression and promoting the expression of the co-stimulatory molecules CD86 and major histocompatibility complex class II (MHC-II) (37). In addition, the phagocytic ability and the immune function of macrophages were also enhanced by anti–PD-L1 therapy, which activate T cells in the TME and eradicate cancer cells (37). Therefore, anti–PD-L1 therapy may repolarize macrophages, enhance the phagocytic ability of macrophages, and ameliorate tumor microenvironment in some patients.

5 Targeting macrophages in the tumor microenvironmentAs TAM was involved in tumor immunity and tumor development, it may become a promising target in the future. Current treatment strategies targeting macrophages can be roughly divided into two categories: depletion of TAM and reprogramming of TAM (Supplementary Figure 1). In order to ensure the treatment efficacy, targeting TAMs was frequently combine with other treatment in clinical studies, such as immunotherapy, chemotherapy, and radiotherapy (Table 1) (38–48).

Table 1 Selected clinical trials of agents targeting tumor-associated macrophages.

5.1 Depletion of TAMDepletion of macrophages in the tumor microenvironment may be an effective treatment strategy for cancer, either alone or in combination with chemotherapy. Inhibition of the signal transduction axis of colony-stimulating factor-1/colony-stimulating factor 1 receptor (CSF1/CSF1R), which is necessary for macrophage survival, can induce apoptosis of macrophages. On the one hand, inhibition of CSF-1R combined with radiotherapy or chemotherapy can improve T-cell response. Blockade of CSF1R signaling can effectively deplete the immunosuppressive TAM and then stimulate the CD8+ T-cell response, resulting in prolonged survival in glioblastoma brain tumors (49). At present, CSF1R inhibitors in combination with chemotherapy have been tried in clinical trials in some cancers, such as localized prostate cancer and orthotopic glioblastoma (49, 50). In addition, blocking CSF1/CSF1R can improve the efficacy of a variety of immunotherapies, including CD-40 agonists (51) and PD-1 inhibitors (52).

As TAM was transformed from monocytes, blocking the recruitment of inflammatory monocytes in the circulation to the tumor site was another method to reduce the TAM in tumor microenvironment. Recruitment of monocytes from bone marrow to tumor site is dependent on C-C motif ligand 2 (CCL2)-CC chemokine receptor 2 (CCR2) signal transduction (53). Inhibition of CCR2 causes monocyte retention in bone marrow and leads to depletion of monocyte in the peripheral circulation, reduction of monocyte recruitment to the primary tumor sites and metastatic foci, and consequent reduction of TAM number, resulting in tumor shrinkage and survival improvement (54–56).

Other pathways involved in macrophage recruitment include CXCL12-CXCR4 and angiopoietin 2 (ANG2)–TIE2 axis (57–59). Therefore, depletion of TEM could cause vascular destruction, neutralization of ANG2 can improve the response to vascular VEGFA blockade, and inhibition of TEM recruitment can inhibit tumor growth (60).

5.2 Reprogramming of TAMAs macrophage was the main phagocyte and antigen-presenting cell in the tumor, the immune stimulation function of macrophage was lost after removal of TAMs. Therefore, reprogramming or repolarization of TAM to enhance its anti-tumor function and limit the tumor-promoting properties is a more attractive strategy for cancer treatment. For example, in the mouse model of breast cancer, TAM represents the main source of IL-10 and inhibition of IL-10 signal transduction can significantly improve the efficacy of chemotherapy. The IL-10 secreted by TAM inhibits the IL-12 produced by APCs, thereby inhibiting the anti-tumor response of CD8+ T cells induced by paclitaxel and carboplatin (23). In addition, the repolarization of TAM makes it specifically express proinflammatory cytokine IFN-α, which could activate NK cells and T cells in the tumor environment and significantly slow the tumor growth in the mouse model (61). The epigenetic reprogramming of macrophages by inhibiting histone deacetylase (HDAC) can also trigger an immune response of T cells (62, 63). In the breast cancer model, the selective class-IIa HDAC inhibitor induces the anti-tumor macrophage phenotype, promotes the T-cell immune response, and increases the response to chemotherapy and immune checkpoint inhibitors (62). In addition, the activation of PI3K signaling in macrophages can drive the immunosuppressive activity in TAM, whereas inhibition of PI3K pathway can re-program macrophages and enhances T-cell response (64, 65).

5.3 Macrophage cell therapyCAR-T cells are reported to be effective in hematological malignancies, whereas the efficacy of CAR-T therapy remains dismal in solid tumors, as the entry of T cells into tumors is restrained (66, 67). However, CAR-macrophages (CAR-M) overcome this disadvantage as the macrophages in the TME could be replenished by circulating monocytes. CAR expression could enhance the antigen-dependent function of macrophage, such as the secretion of cytokines, polarization, enhanced phagocytic ability, and anti-cancer activity (68). CAR-M cells mediate phagocytosis and exhibit M1 functions in a relatively stable way and exert anti-tumor effects in the primary and metastatic tumors (69). Currently, several clinical trials are under way or developed to evaluate the anti-cancer efficacy of CAR-M in different tumors.

5.4 Combination of targeting macrophages and anti–PD-1 therapy in cancerThe combination of targeting macrophages and anti–PD-1 therapy in cancers has been investigated in vitro and in vivo (37, 70–72). As we have noted above, repolarization of TAM was considered as a promising strategy for cancer treatment and this approach can potentiate anti–PD-1 therapy efficacy in hepatocellular carcinoma (72). Chemotherapy and radiotherapy may reset macrophages toward a M1 phenotype and improve the efficacy of immunotherapy in cancer (71). Vinblastine can drive the polarization of TAMs to the M1 phenotype by activating NF-κB, increase CD8+ T-cell populations, and improve the survival outcome of malignant tumor immunotherapy (71). Bi-target treatment such as PD-1–IL-2 cytokine variant (IL2v) employed anti–PD-1 as a target moiety, which is fused into an immuno-stimulatory IL2v, can improve the therapeutic efficacy by reprogramming immunosuppressive TAMs (70). In conclusion, targeting macrophages combined with anti–PD-1 therapy may be a promising strategy to overcome drug resistance in patients with cancer.

6 ConclusionMacrophages are involved in various cell activities in cancer, and the interaction between macrophages and cancer cells or other immune cells was associated with tumor development. As an important part of the tumor microenvironment, TAMs may be a promising treatment target in cancer. Targeting macrophages alone or combined with radiotherapy, chemotherapy, and immune-checkpoint inhibitors may produce excellent anti-tumor activity. In addition, the upstream and downstream pathways that could regulate the function of macrophages could also serve as therapeutic targets. In particular, the use of genetic engineering to reprogram macrophages to transform tumor promoting TAM into anti-tumor macrophages is of great clinical application. Although the combination of targeting macrophages and anti–PD-1 therapy in cancers has been tried in clinical trials or preclinical experiments, this treatment approach was still in its infancy and needs further investigation. Stumbling blocks in the transformation and application of TAM targeted therapy include the diversity and plasticity of mononuclear phagocytes in the TME (73). The dissection of the TME at the single-cell level confirmed the diversity of macrophages and their relationship with other immune cells (22, 31), which provides a rationale to selectively deplete tumor-promoting macrophages and eliminate tumor. The application of macrophage targeted therapy in cancer is still in infancy, and the efficacy and tolerance need to be confirmed in more experiment and clinical trials in the future.

Author contributionsLZ: Writing – original draft. TZ: Writing – original draft, Formal analysis, Data curation, Conceptualization. RZ: Resources, Project administration, Writing – original draft. CC: Methodology, Investigation, Writing – original draft. JL: Writing – review & editing, Visualization, Validation, Supervision, Funding acquisition.

FundingThe author(s) declare financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. This study was supported by the Scientific Research Project of Hunan Provincial Health Commission (No. 20231607), the Scientific Research Launch Project for new employees of the Second Xiangya Hospital of Central South University, Beijing Xisike Clinical Oncology Research Foundation (Grant No. Y-Young2023-0175), the funding of National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 82300116), the Natural Science Foundation of Changsha City (CN) (No. kq2208304), and Natural Science Foundation of Hunan Province (No. 2023JJ40878).

Conflict of interestThe authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s noteAll claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary materialThe Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fimmu.2024.1381225/full#supplementary-material

Supplementary Figure 1 | Targeting macrophages in the tumor microenvironment.

References2. Shi D, Gao L, Wan XC, Li J, Tian T, Hu J, et al. Clinicopathologic features and abnormal signaling pathways in plasmablastic lymphoma: a multicenter study in China. BMC Med. (2022) 20:483. doi: 10.1186/s12916-022-02683-9

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

3. Kamdar M, Solomon SR, Arnason J, Johnston PB, Glass B, Bachanova V, et al. Lisocabtagene maraleucel versus standard of care with salvage chemotherapy followed by autologous stem cell transplantation as second-line treatment in patients with relapsed or refractory large B-cell lymphoma (TRANSFORM): results from an interim analysis of an open-label, randomised, phase 3 trial. Lancet. (2022) 399:2294–308. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(22)00662-6

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

4. Del Bufalo F, De Angelis B, Caruana I, Del Baldo G, De Ioris MA, Serra A, et al. GD2-CART01 for relapsed or refractory high-risk neuroblastoma. N Engl J Med. (2023) 388:1284–95. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2210859

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

5. Janjigian YY, Shitara K, Moehler M, Garrido M, Salman P, Shen L, et al. First-line nivolumab plus chemotherapy versus chemotherapy alone for advanced gastric, gastro-oesophageal junction, and oesophageal adenocarcinoma (CheckMate 649): a randomised, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet. (2021) 398:27–40. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)00797-2

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

6. Li JW, Deng C, Zhou XY, Deng R. The biology and treatment of Epstein-Barr virus-positive diffuse large B cell lymphoma, NOS. Heliyon. (2024) 10:e23921. doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2023.e23921

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

7. Goc J, Lv M, Bessman NJ, Flamar AL, Sahota S, Suzuki H, et al. Dysregulation of ILC3s unleashes progression and immunotherapy resistance in colon cancer. Cell. (2021) 184:5015–30 e16. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2021.07.029

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

8. Scholler N, Perbost R, Locke FL, Jain MD, Turcan S, Danan C, et al. Tumor immune contexture is a determinant of anti-CD19 CAR T cell efficacy in large B cell lymphoma. Nat Med. (2022) 28:1872–82. doi: 10.1038/s41591-022-01916-x

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

9. Hirz T, Mei S, Sarkar H, Kfoury Y, Wu S, Verhoeven BM, et al. Dissecting the immune suppressive human prostate tumor microenvironment via integrated single-cell and spatial transcriptomic analyses. Nat Commun. (2023) 14:663. doi: 10.1038/s41467-023-36325-2

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

11. Chan JM, Quintanal-Villalonga A, Gao VR, Xie Y, Allaj V, Chaudhary O, et al. Signatures of plasticity, metastasis, and immunosuppression in an atlas of human small cell lung cancer. Cancer Cell. (2021) 39:1479–96 e18. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2021.09.008

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

15. Tang Z, Davidson D, Li R, Zhong MC, Qian J, Chen J, et al. Inflammatory macrophages exploit unconventional pro-phagocytic integrins for phagocytosis and anti-tumor immunity. Cell Rep. (2021) 37:110111. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2021.110111

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

16. Zheng X, Jiang Q, Han M, Ye F, Wang M, Qiu Y, et al. FBXO38 regulates macrophage polarization to control the development of cancer and colitis. Cell Mol Immunol. (2023) 20:1367–78. doi: 10.1038/s41423-023-01081-2

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

17. Zhang G, Gao Z, Guo X, Ma R, Wang X, Zhou P, et al. CAP2 promotes gastric cancer metastasis by mediating the interaction between tumor cells and tumor-associated macrophages. J Clin Invest. (2023) 133:e166224. doi: 10.1172/JCI166224

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

18. Chen S, Saeed A, Liu Q, Jiang Q, Xu H, Xiao GG, et al. Macrophages in immunoregulation and therapeutics. Signal Transduct Target Ther. (2023) 8:207. doi: 10.1038/s41392-023-01452-1

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

19. Park MD, Reyes-Torres I, LeBerichel J, Hamon P, LaMarche NM, Hegde S, et al. TREM2 macrophages drive NK cell paucity and dysfunction in lung cancer. Nat Immunol. (2023) 24:792–801. doi: 10.1038/s41590-023-01475-4

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

20. Yu Y, Dai K, Gao Z, Tang W, Shen T, Yuan Y, et al. Sulfated polysaccharide directs therapeutic angiogenesis via endogenous VEGF secretion of macrophages. Sci Adv. (2021) 7:eabd8217. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.abd8217

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

21. Casanova-Acebes M, Dalla E, Leader AM, LeBerichel J, Nikolic J, Morales BM, et al. Tissue-resident macrophages provide a pro-tumorigenic niche to early NSCLC cells. Nature. (2021) 595:578–84. doi: 10.1038/s41586-021-03651-8

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

22. Leader AM, Grout JA, Maier BB, Nabet BY, Park MD, Tabachnikova A, et al. Single-cell analysis of human non-small cell lung cancer lesions refines tumor classification and patient stratification. Cancer Cell. (2021) 39:1594–609 e12. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2021.10.009

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

23. Ruffell B, Chang-Strachan D, Chan V, Rosenbusch A, Ho CM, Pryer N, et al. Macrophage IL-10 blocks CD8+ T cell-dependent responses to chemotherapy by suppressing IL-12 expression in intratumoral dendritic cells. Cancer Cell. (2014) 26:623–37. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2014.09.006

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

26. Li JW, Shi D, Wan XC, Hu J, Su YF, Zeng YP, et al. Universal extracellular vesicles and PD-L1+ extracellular vesicles detected by single molecule array technology as circulating biomarkers for diffuse large B cell lymphoma. Oncoimmunology. (2021) 10:1995166. doi: 10.1080/2162402X.2021.1995166

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

27. Janjigian YY, Kawazoe A, Bai Y, Xu J, Lonardi S, Metges JP, et al. Pembrolizumab plus trastuzumab and chemotherapy for HER2-positive gastric or gastro-oesophageal junction adenocarcinoma: interim analyses from the phase 3 KEYNOTE-811 randomised placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. (2023) 402:2197–208. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(23)02033-0

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

28. Brahmer JR, Drake CG, Wollner I, Powderly JD, Picus J, Sharfman WH, et al. Phase I study of single-agent anti-programmed death-1 (MDX-1106) in refractory solid tumors: safety, clinical activity, pharmacodynamics, and immunologic correlates. J Clin Oncol. (2023) 41:715–23. doi: 10.1200/JCO.22.02270

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

30. Zhang H, Liu L, Liu J, Dang P, Hu S, Yuan W, et al. Roles of tumor-associated macrophages in anti-PD-1/PD-L1 immunotherapy for solid cancers. Mol Cancer. (2023) 22:58. doi: 10.1186/s12943-023-01725-x

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

31. Qi J, Sun H, Zhang Y, Wang Z, Xun Z, Li Z, et al. Single-cell and spatial analysis reveal interaction of FAP(+) fibroblasts and SPP1(+) macrophages in colorectal cancer. Nat Commun. (2022) 13:1742. doi: 10.1038/s41467-022-29366-6

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

32. Zhang Y, Chen H, Mo H, Hu X, Gao R, Zhao Y, et al. Single-cell analyses reveal key immune cell subsets associated with response to PD-L1 blockade in triple-negative breast cancer. Cancer Cell. (2021) 39:1578–93 e8. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2021.09.010

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

33. Ning J, Hou X, Hao J, Zhang W, Shi Y, Huang Y, et al. METTL3 inhibition induced by M2 macrophage-derived extracellular vesicles drives anti-PD-1 therapy resistance via M6A-CD70-mediated immune suppression in thyroid cancer. Cell Death Differ. (2023) 30:2265–79. doi: 10.1038/s41418-023-01217-x

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

34. You Q, Wang F, Du R, Pi J, Wang H, Huo Y, et al. m(6) A reader YTHDF1-targeting engineered small extracellular vesicles for gastric cancer therapy via epigenetic and immune regulation. Adv Mater. (2023) 35:e2204910. doi: 10.1002/adma.202204910

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

35. Li J, Wu C, Hu H, Qin G, Wu X, Bai F, et al. Remodeling of the immune and stromal cell compartment by PD-1 blockade in mismatch repair-deficient colorectal cancer. Cancer Cell. (2023) 41:1152–69 e7. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2023.04.011

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

36. Hu J, Zhang L, Xia H, Yan Y, Zhu X, Sun F, et al. Tumor microenvironment remodeling after neoadjuvant immunotherapy in non-small cell lung cancer revealed by single-cell RNA sequencing. Genome Med. (2023) 15:14. doi: 10.1186/s13073-023-01164-9

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

37. Song CH, Kim N, Nam RH, Choi SI, Jang JY, Kim JW, et al. Combination treatment with 17beta-estradiol and anti-PD-L1 suppresses MC38 tumor growth by reducing PD-L1 expression and enhancing M1 macrophage population in MC38 colon tumor model. Cancer Lett. (2022) 543:215780. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2022.215780

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

38. Choueiri TK, Kluger H, George S, Tykodi SS, Kuzel TM, Perets R, et al. FRACTION-RCC: nivolumab plus ipilimumab for advanced renal cell carcinoma after progression on immuno-oncology therapy. J Immunother Cancer. (2022) 10:e005780. doi: 10.1136/jitc-2022-005780

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

39. Nywening TM, Wang-Gillam A, Sanford DE, Belt BA, Panni RZ, Cusworth BM, et al. Targeting tumour-associated macrophages with CCR2 inhibition in combination with FOLFIRINOX in patients with borderline resectable and locally advanced pancreatic cancer: a single-centre, open-label, dose-finding, non-randomised, phase 1b trial. Lancet Oncol. (2016) 17:651–62. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(16)00078-4

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

40. Haag GM, Springfeld C, Grun B, Apostolidis L, Zschabitz S, Dietrich M, et al. Pembrolizumab and maraviroc in refractory mismatch repair proficient/microsatellite-stable metastatic colorectal cancer - The PICCASSO phase I trial. Eur J Cancer. (2022) 167:112–22. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2022.03.017

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

41. Gilbert MR, Dignam JJ, Armstrong TS, Wefel JS, Blumenthal DT, Vogelbaum MA, et al. A randomized trial of bevacizumab for newly diagnosed glioblastoma. N Engl J Med. (2014) 370:699–708. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1308573

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

42. Cassier PA, Italiano A, Gomez-Roca C, Le Tourneau C, Toulmonde M, D'Angelo SP, et al. Long-term clinical activity, safety and patient-reported quality of life for emactuzumab-treated patients with diffuse-type tenosynovial giant-cell tumour. Eur J Cancer. (2020) 141:162–70. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2020.09.038

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

43. Gomez-Roca C, Cassier P, Zamarin D, Machiels JP, Perez Gracia JL, Stephen Hodi F, et al. Anti-CSF-1R emactuzumab in combination with anti-PD-L1 atezolizumab in advanced solid tumor patients naive or experienced for immune checkpoint blockade. J Immunother Cancer. (2022) 10:e004076. doi: 10.1136/jitc-2021-004076

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

44. Machiels JP, Gomez-Roca C, Michot JM, Zamarin D, Mitchell T, Catala G, et al. Phase Ib study of anti-CSF-1R antibody emactuzumab in combination with CD40 agonist selicrelumab in advanced solid tumor patients. J Immunother Cancer. (2020) 8:e001153. doi: 10.1136/jitc-2020-001153

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

45. Razak AR, Cleary JM, Moreno V, Boyer M, Calvo Aller E, Edenfield W, et al. Safety and efficacy of AMG 820, an anti-colony-stimulating factor 1 receptor antibody, in combination with pembrolizumab in adults with advanced solid tumors. J Immunother Cancer. (2020) 8:e001006. doi: 10.1136/jitc-2020-001006

留言 (0)