The active total care of a child’s body, mind, and spirit that includes supporting the family is known as palliative care for children.[1] Chronic illness affects 3.49% of children aged 0–14 in Kerala, South India.[2] Twenty-six percent of individuals in need have improved access to palliative care in Kerala, thanks to the ‘Pain and Palliative Care Society’ and neighborhood networks in palliative care, which provide local community-based care.[3] Data on caregiver issues of paediatric non-malignant palliative care are suboptimal, despite this remarkable advancement of palliative care in Kerala. Assessment of caregiver satisfaction related to communication and decision-making has been studied in adults but hardly studied in children with complex chronic conditions who have multiple unmet needs for palliative care.[4] Complex chronic conditions are defined as ‘any medical condition that can reasonably be expected to last at least 12 months (unless death intervenes) and involves either several different organ systems or one organ system severely enough to require specialty paediatric care and some period of hospitalisation in a tertiary care centre’.[5]

Hospitalisation for palliative care is usually to decide on the management plans for intermittent crises, including sharing advanced decisions with the parents regarding interventions.[6] Given the unpredictability of their course, chronic illnesses in children can come with heavy physical, psychological, financial, and social consequences for both the patient and caregiver. Extrapolating adult palliative care data is inadequate because there are distinct patterns of paediatric life-threatening conditions.

Exploring data on primary caregiver experiences of dealing with chronically ill children (CIC) strengthens the ability of paediatricians to improve the quality of care by detecting unmet needs in paediatric palliative care and understanding their original concerns instead of presumed needs. Caregiver concerns may be strikingly different from what the paediatrician considers the first issue to be addressed in CIC. Such knowledge helps to avoid misunderstandings and frustration of parents while clinicians manage chronic illnesses. It also aids clinicians in creating realistic plans of care for these patients. Furthermore, potentially modifiable factors in the current health system can be identified and modified to improve comprehensive child and family care. Hence, there is a definite need to study the issues, unmet needs, and challenges faced by families of CIC.

This hospital-based study aims to identify and describe the most worrisome issues for the primary caregiver of a chronically ill child admitted to the paediatric ward of a government medical college in Kerala, South India.

MATERIALS AND METHODSSRQR guidelines were followed for conducting and reporting this research.[7] The research protocol was approved by the Institutional Research Committee and the Ethical Committee. Thematic analysis is the method chosen for qualitative data analysis in this study, as the aim was to describe caregiver experiences and explore their most problematic issues. The study population selected were parents of children aged <13 years with non-malignant life-limiting illnesses admitted to the paediatric department of a government medical college in Kerala between 1 July 2021 and 28 February 2022.

Those participants who could not speak the local language (Malayalam), those patients who had surgically correctable or medically curable conditions, or those who were recognised to be highly ill were excluded from this study.

Written informed consent was obtained from all the participants in the study before the interview [Appendix A]. After establishing a good rapport with the participants, in-depth interviews were conducted by the principal investigator during the study period with a conversational approach so that they could freely share their own experiences, issues, and needs. An interview guide was used for structuring the interview. The interview was conducted by the principal investigator in a private room in the hospital. Data collection included recording and transcribing the interviews into text. Field notes were also written during the interviews. The interview began with an open question: ‘Can you tell me what worries you the most regarding your child’. More detailed responses were elicited by asking about their important needs, physical, sleep, treatment, financial, drug availability, and family issues [Appendix B]. Interviews lasted an average of 1 hour. A consecutive sampling technique was used until data saturation was achieved. In the event of the caregiver having an emotional breakdown, the recording would be immediately stopped. The interviewer would provide them with empathetic support. These caregivers were referred to the psychiatrist and also received psychological counseling. Caregivers continued to have regular follow-ups with the psychology team, even after the discharge of the chronically ill child (CIC).

Information bias was planned to be minimised by audio recording during data collection. To prevent selection and information bias, the third author, who was not in direct contact with the participants, was involved in the process of identifying codes and extracting meaning units. The validity of this was confirmed by the other authors who cross-checked it. The first author translated the original text, which was in Malayalam, to English. The second author has been formally trained in paediatric palliative care. The third author is trained in qualitative research methodology.

Methodological orientationInitially, a ‘meaning unit’, which is words, sentences, or paragraphs containing aspects that answer the research question, was identified. The label of a meaning unit has been referred to as a ‘Code’.[8] ‘Themes’ represent the overall concept on an interpretative latent level.[9] The ‘codes’ were identified from the transcripts as the most frequently repeated issues, and then, they were grouped into ‘subthemes’ based on similarities. Finally, the issues and needs were broadly classified as ‘themes’. As there was marked heterogeneity of the chronic diseases and subthemes were finer in nature, data saturation was attained only after 24 interviews. It was at this point that the variety of issues faced by the caregivers was fully understood, and no further dimensions or insights could be found. Inductive approach of thematic analysis by Braun and Clarke was followed in this study.[10]

RESULTSAs there were two CICs in one family, there were a total of 25 CICs. Among them, 14 were male (56%). Interviews were conducted with 24 primary caregivers. The interview was done with 15 mothers, eight fathers, and one paternal grandmother who were the primary caregivers of the CIC. The age group of patients with non-malignant life-limiting illnesses ranged from 9 months to 13 years of age. The baseline characteristics of the patients and their caregivers are given in Table 1.

Table 1: Baseline characteristics.

Major system involved Chronic neurological illness (n=18) Chronic kidney disease (n=1) Chronic haematological illness (n=2) Chronic respiratory illness (n=1) Inborn errors of metabolism (n=3) Age range (y) 1.5–12.5 12 8–11 10 0.75–12.5 Male: Female 12:6 Male 1:1 Female 1:2 Average age of mothers 27–45 36 36–40 38 28–45 Average age of fathers 32–55 45 45–48 48 35–55 Education of mother Secondary school and above Secondary school Bachelor’s degree Secondary school Secondary school Average number of hospitalisations 5 admissions/year 24 admissions/year 12 admissions/year 8 admissions/year 3 admissions/year Unemployed fathers n(%) 7 (38.8%) 1 (100%) 1 (50%) 1 (100%) 1 (33%)The average age of mothers was 35 (standard deviation [SD] ±5.46) and the average age of fathers was 41.8 (SD ±6.32). The length of continuous hospital stay for the chronically ill child varied between 15 days and 350 days in a year [Table 2]. One mother had two children with life-limiting illnesses. By the end of the study period, 4 of the 25 CIC had succumbed to death. Twenty-two of the 25 (88%) who required recurrent and prolonged hospital-based palliative care were due to chronic neurological conditions.

Table 2: Major diagnosis, mean hospital stay and outcomes of the chronically ill children.

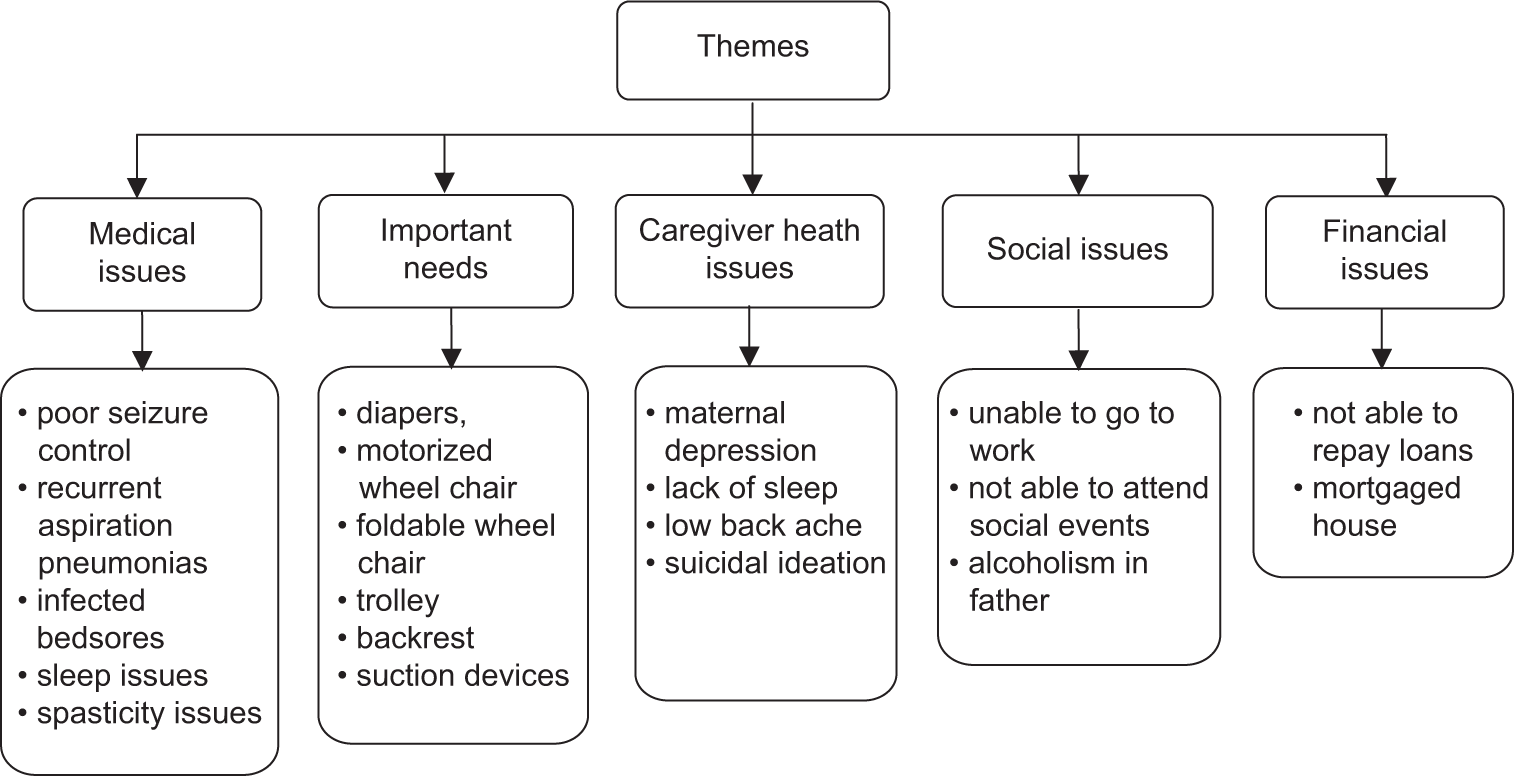

Participant ID (cases) Major diagnosis Mean hospital stay in a year Outcome at the end of the study period 1, 2, 3, 11, 13, 15, 16, 20, 22 Spastic quadriplegia with complications 28 days Alive 8, 9 Spinal muscular dystrophy 90 days Case 9: ExpiredFigure 1 illustrates the identified ‘themes’ of caregiver issues and needs. Sleep issues in caregivers and the CIC, poor seizure control, excessive oral secretions and infected bed sores in the CIC were the major medical concerns reported. It was observed that a ‘diaper’ was the crucial and universally necessary item, according to caretakers, for all CICs. Common codes identified are also included in Figure 1.

Export to PPT

Thematic analysisThe themes to be analysed were selected based on the answers to the primary question of what was the most problematic issue faced by the primary caregiver while taking care of a child with a life-limiting illness. The cardinal statements of the caregiver regarding their most worrisome issue and major subthemes are described below, in italics, to make transparent the process from raw data to results.[11] Minor subthemes are described in Table 3.

Table 3: Minor subthemes and meaning units.

Subthemes Meaning units Poor sleep pattern in patient ‘She gets up a hundred times during sleep’ (case 5, mother of 2-year-old female) Fear of the future of the child ‘My main concern is who will take care of him once I pass away’ (case 2, mother of a 2-year-old boy) Failing to understand the child’s pain ‘I wish I could understand why he is crying. When he was younger, he could at least tell me where his pain was’ (case 6, mother of a 12.5-year-old boy with neuroregression) Procedural pain ‘My child had suffered so much pain after they put the chest tubes’ (case14, mother of a 10-year-old girl) Medical issues of patients Poor seizure controlAccording to the majority of the participants, poor seizure control was the primary concern.

‘While walking, he abruptly falls forward, hurting himself each time’ (case 2, mother of a 7-year-old boy).

Missing antiepileptic dosages happen because the tertiary hospital’s 1-time supply of antiepileptic to a single patient is given for a maximum of 1 or 2 months at a time. Moreover, the unavailability of certain antiepileptic drugs from peripheral health centres also resulted in poor seizure control.

I was unable to obtain her medication (antiepileptic) from our location. Whatever medication we got from here has been used up for a while. She is now experiencing prolonged seizures. (Mother, case 4).

Excessive oral secretions‘I keep wiping his face and neck and change his bibs all the time because it gets drenched with saliva, and if I get a little late, he smells very bad’ (case 3, mother of 1.5-year-old).

Spasticity issues‘It is challenging for me to turn him by myself, but I know that unless I do, his bedsores won’t heal’ (case 1, mother of 12.5-year-old obese male).

Inability of self-careCaregivers of older female CICs are concerned about managing menstruation. They were concerned about the inability of CICs to use menstrual pads by themselves.

She used to dance very well. But now she can’t even stand or walk. She even lost an eye... After all that she’s been through (sighs), now, my worry is about how she will manage when she gets her periods. she cannot even feel the wetness of urine or blood. (Grandmother, case 25).

Important needsParents of almost all the CIC reported that they required diapers more than any other material or device. They also said there is a very high requirement for diapers. Many participants expressed that if they could get a trolley on which they could clean and bathe the bedridden CIC, they would be able to provide better personal hygiene. He needs about 13 packets of diapers every month. I spend around 6000 rupees for diapers alone in a month (Father, case 16).

Caregiver health issuesEleven mothers were on antidepressants (45%). Lack of sleep and resultant fatigue was the most common health issue reported by the participants.

I have been on treatment for depression since 2 months of his birth (Mother, case 2).

Sleep deprivation among caregivers‘Since his birth, I have not been able to get more than two hours of uninterrupted sleep’ (case 3, mother of 1.5-year-old male).

Suicidal thoughts in the primary caregiver‘I had already made the decision to terminate my life when he was little’ (case 11, mother of a 12-year-old boy).

Socioeconomic issues Delay in obtaining fundsDelay in obtaining funds and delay in the paperwork needed for renal transplantation resulted in at least two admissions in 1 week for a child with the end-stage renal disease with recurrent pulmonary oedema.

We are running around for money for his kidney transplantation. All we want is the papers to be ready as soon as possible (Father, case 23).

Lack of awareness of palliative care facilitiesSome families drive far distances just to change feeding tubes because they are unaware of local palliative care providers.

In our place, we do not know of any palliative care nurse who can come to our home to change her feeding tube (Mother, case 5).

Financial constraintsTwelve families were under the burden of bank loans (48%). Debts were incurred mainly for the treatment of the CIC.

They said he would be able to walk, so I had to take bank loans repeatedly to pay for his treatment. I once even prayed that he better die after my wife doused herself in kerosene. To live and let him live, I took bank loan again, bringing my total debt to ten lakh rupees (Father, case 22).

Late referral‘I regret that we brought her here so late. They could have referred her before she became so sick’ (case 17, mother of a 9-month-old female).

False hopes‘We believed him (Dr X) when he said there is a cure for my child. Now we know we are giving her good care even if we cannot cure her’ (case 7, father of 4-year-old girl).

Loss of job‘How can he go to work when we have two children with SMA’ (cases 8, 9; mother of a 6-year boy and 10-year-old girl).

DISCUSSIONChildren with chronic critical illnesses are reported to have five times longer hospital stays than other patients.[12] According to Higginson et al., hospital-based palliative care teams improve care for patients and families.[13] Neurological illness is the major system involved in our group of CIC. Fuhrer reported a similar pattern in CIC (75%).[14] Severe refractory epilepsy, as defined by Kwan and Brodie, is associated with a high risk of mortality and morbidity, including sudden unexplained deaths.[15] The lack of availability of antiepileptic drugs in the peripheral health centres causes a significant financial drain since they have to travel to tertiary care centres to procure the same. If these drugs were made available in the peripheral health units as part of the Rashtriya Kishor Swasthya Karyakram by the National Health Mission, this would help reduce the out-of-pocket expense and indirect cost incurred for travel.

Excessive oral secretion is a main concern for many caregivers, which is often not considered an important issue by some paediatricians. The sudden onset of prolific respiratory secretions at the time of death or ‘death rattle’ can be controlled well with morphine, especially in neurogenic pulmonary oedema.[16] End-of-life care challenges were not included in the interview guide. Endof-life care was offered to three children (cases 5, 9, 17). However, it could not be given to one child who suddenly deteriorated (case 14). This mother’s main worry was the pain her child underwent after two intercostal drainage insertions. Pain prevention and control is another important issue that should be addressed from the intensive care unit itself and continued till the very end of life. Reflective open-ended questions help to optimise treatment by the palliative care team after aligning with the care goals of the patient and caregivers.[17]

Parental need to engage with children and the need to listen to them is recommended for normal children,[18] but our study participants (cases 6 and 15) revealed that they felt despair when they could not communicate with their children. Cases 7 and 17 experienced a great deal of confusion, emotional stress, and financial loss due to contradictory opinions given by different systems of medicine regarding the cure of the disease. False hopes contributed to their depression. Treating units can use the language of the right hope to promote patient welfare without denying the facts to the caregivers of the patients.[19] False hopes can be avoided by providing facts about the nature of illness and the effectiveness of various end-of-life care plans. Caregivers of CIC expressed relief on the discontinuation of futile treatments and on the provision of meaningful hopes.

Parents of cases 1, 6, 8, and 23 revealed a feeling of unease when the subject of an eventual transfer to adult care was brought up, which is consistent with Menon J et al. findings.[20] Significant psychological issues in both children and their parents have been reported due to the increased financial burdens due to the loss of jobs, especially in pandemic situations.[21] A system to access the available government funding without delay would mitigate these caregivers’ distress, as Govindaraj et al. suggested in a similar setting with a different group of paediatric patients.[22]

Paediatricians often presume that the most important requirements of children with chronic illness (especially those with chronic neurological illness) are equipment such as cerebral palsy chairs, callipers, or orthoses.[23] Contrary to such presumptions, this study reveals that the majority of them needed ‘diapers’. The purchase of diapers accounts for a significant expense for the chronically ill child. Provisions for free-of-cost diapers through the government or NGOs will help tackle this major concern shared by the caregivers in the present study.

Sleep issues in both parents and the chronically ill child are another significant problem that is not usually addressed during routine rounds by paediatricians. Increased nighttime awakenings were reported in our study subjects. This finding is similar to the study of Hysing et al.[24] Caregiver depression and fatigue were found in those participants whose sleep was disrupted due to nighttime care. Chronic sleep deprivation in the caregivers negatively affects the care of CIC.[24] Adequate rest for these mothers at home will be possible through the establishment of palliative day care centres at the peripheral level with community participation and involvement of local self-government.[25]

Advice to mothers of spastic quadriplegic children to frequently change their position to prevent bedsores is not going to be effective or practical unless the rest of the family members or palliative care staff lend the mother/primary caregivers a helping hand in doing this, particularly in the case of obese children. Networking of various governmental and non-governmental palliative care centres would boost the services provided to the chronically ill and their families.[26] Nursing interventions such as changing feeding tubes, urinary catheters, and dressing bedsores can be coordinated with such service providers. The treating paediatricians should contact local palliative care providers before discharging these in-patients so that continuum of care can be maintained.

CONCLUSIONThe challenges faced by caregivers of children with complex chronic conditions are multifaceted. Their most worrisome issues related to medical issues are the occurrence of breakthrough seizures and development of infected bedsores. The most important material hardship reported was diaper need. Caregiver issues such as sleep deprivation and maternal depression must be identified and addressed while providing comprehensive palliative care.

留言 (0)