Cardiometabolic diseases are among the most common causes of death globally and are prevalent among young adults.[1,2] A report of the 2017–2018 prevalence of hypertension among adults in the United States of America, using the 2017 American College of Cardiology and American Heart Association (ACC/AHA) diagnostic criteria, revealed a prevalence of 22.4% among those aged 18–39 years,[3] while Ahammed et al. found[2] a prevalence of 63.48% among 15–49 year olds based on the ACC/AHA criteria. An institutional-based cross-sectional study conducted in Ethiopia revealed that metabolic syndrome prevalence is high among Ethiopian Public Health Institute staff, with central obesity, low high-density lipoprotein, and hypertension as significant risk factors.[4] The study was mainly conducted among young employees at the institute. Available regional evidence indicates that obesity and related cardiometabolic disorders are highly prevalent in the United Arab Emirates, with a 2–3-fold increase in overweight and obesity prevalence between 1989 and 2017. However, precise prevalence estimates are difficult due to methodological heterogeneity in epidemiological studies.[5] In another study of pre-hypertension and hypertension among college students aged 17–23 years in Kuwait, Al-Majed and Sadek[6] found a prevalence of 7% for hypertension. Among those found to be hypertensive, 21.4% met the criteria for dyslipidaemia, 17.9% had high fasting blood glucose levels and 3.6% had high haemoglobin A1C levels. Similarly, findings from the Kuwait Diabetes Epidemiology study indicated a diabetes prevalence of 5.4% and 14.2% in adults aged 20–29 and 30–44, respectively.[7] The increasing prevalence of cardiometabolic diseases noted across all age groups globally has been observed to be paralleled by an associated increase in its complications and mortality.[8]

Advance care planning (ACP) entails planning for one’s current and future healthcare needs through discussions about personal values, beliefs, and preferences with relevant people such as relatives and healthcare givers.[9] Through ACP, individuals develop health-related care and support plans for future periods when they may lack the capacity to make such decisions by themselves, thereby exercising their autonomy during such periods. It is recommended for patients at risk of losing their decision-making capacity due to acute and chronic disease complications. Cardiometabolic diseases are known to be associated with acute and chronic complications that increase disease-related mortality.[10] Therefore, planning for advance care at the end of life might be considered imperative.

According to Baygi et al.[11], the overall prevalence of some cardiometabolic risk factors is higher in military personnel. Interestingly, a similar high prevalence of cardiometabolic risk factors among office workers in the study by El Mahdy[12] demonstrated a high prevalence of cardiometabolic risk factors among a group of 30–66-year-old private office workers in Egypt. About 89.7% of the study participants reported having three or more cardiometabolic risk factors. Similarly, a cross-sectional multi-national hospital-based study by Kingue et al.[13] conducted among patients in four sub-Saharan countries revealed excessive cardiometabolic risk factors. These findings highlight the need for preventive measures to reduce cardiovascular disease risk and increased attention to health promotion campaigns and public awareness programs. This necessitates the development of prevention and control strategies[13], as it has been demonstrated that preventing cardiometabolic diseases through not smoking, maintaining an average weight, increasing physical activity, eating a healthy diet, and avoiding tobacco use can significantly reduce the risk of developing these conditions.[14]

Identified strategies for the prevention of cardiometabolic diseases, which include regular physical activity and non-current smoking, can increase life expectancy in patients with cardiometabolic multimorbidity.[15] Effective prevention, early detection and risk management can reduce the incidence of cardiometabolic diseases and their associated complications and their costs.[16] However, Ekore et al.[17], in their study on young adults’ attitudes and behaviour toward type 2 diabetes mellitus preventive lifestyle measures, revealed that although the majority (88.1%) of the study participants agreed that it was essential to maintain a healthy lifestyle at a young age, only 16% of them ate fruits on all days of the week, 85.0% indicated that their work did not typically involve a vigorous-intensity activity that caused significant increases in breathing or heart rate for at least 10 min continuously, 45.1% indicated that they do not walk or use a bicycle for travel on a typical day, and 74.2% indicated that they do not do any vigorous-intensity sports, fitness or recreational (leisure) activities that cause significant increases in breathing or heart rate for at least 10 min continuously.

Adoption of the preventive measures was demonstrated to be important due to rare ACP activities observed among patients with limb-threatening ischaemia or diabetes, which, when conducted, mainly was focused on resuscitation-related decisions despite a high risk of death within a year.[18] The Kuwait Ministry of Health established palliative care services in 2011 for patients living with cancer. The services are still only available to cancer patients due to an acute shortage of professional workforce.[19] However, as important as it is, there is a paucity of data on physicians’ involvement or engagement in ACP. Available evidence indicates a low level of engagement of primary care physicians in ACP. Nevertheless, they were willing to participate in related activities whenever necessary.[20] A related study conducted among nurses in Kuwaiti hospitals revealed a favourable disposition toward caring for dying patients. Still, it demonstrated an unfavourable perception toward making conversation with patients about death.[21]

Statement of the problemThe current global practice is to plan for the end-of-life period of persons already terminally ill with chronic diseases. Cardiometabolic diseases are associated with known complications that increase disease-related morbidity and mortality. This is supported by a study conducted among older adults in two African countries that demonstrated the presence of disabilities among patients with cardiometabolic diseases and with higher odds of moderate and severe disabilities among participants with multimorbidity in comparison with those having just minimal cardiometabolic multimorbidity.[22] Hence, there is a need to plan for advance care at the end of life for emergencies that might be linked to complications of cardiometabolic diseases. However, most of the evidence available on ACP is based on studies conducted among older patients at the terminal stage of the respective diseases, such as heart or kidney failure.[23-29]

Given the possibility of known complications also occurring acutely, young adults living with cardiometabolic diseases should not have to wait till the stage of terminal illness (whether acute or chronic) to begin making plans for future healthcare preferences. Thus, the following questions arise: Should discussions related to ACP be initiated with young adults living with cardiometabolic diseases? Although Sandoval et al.[30] demonstrated that the majority of patients expressed willingness to participate in ACP, and they prefer to have these discussions with their primary care providers, and primary care providers are well-positioned to discuss ACP with patients, ACP rates among primary care patients remain suboptimal. Are primary care physicians willing to initiate such discussions? Most importantly, ‘what are the possible barriers that could be perceived as hindering the initiation of such discussions?’

These questions necessitated this pilot study that explored perceived barriers to physicians initiating discussions on ACP with young adults living with cardiometabolic diseases and the willingness of physicians to initiate such conversations.

MATERIALS AND METHODSThe pilot phase of this study commenced in February 2023, and data collection lasted 4 weeks. The participants were consenting family medicine and internal medicine physicians (clinicians) directly providing care for persons living with cardiometabolic disease at Kuwait’s primary, secondary, or tertiary care level. Clinicians not providing direct care for persons in the category and non-consenting family medicine/internal medicine physicians were excluded from the study.

A call for participation was made through direct contact and social media. Data were collected with an electronic version of the modified DECIDE questionnaire[20] after obtaining informed consent from the study participants. The DECIDE® questionnaire was self-administered and distributed to the participants through Google Forms. Responses were individually submitted electronically. The collected data was extracted from Google Forms and placed onto Google Sheets, a cloud-based electronic spreadsheet with which both descriptive and inferential data analysis can be conducted. The collected data was cleaned before analysis.

Data management and analysisData obtained from the study was analysed using Google Sheets (spreadsheet). Relevant descriptive analysis was done.

Ethical considerationsEthical approval was not obtained for the pilot phase. However, individual informed consent was obtained from the prospective participants.

RESULTS DemographicsThere was a response rate of 10.3% (22 responses out of 214 link clicks). Twenty-two people participated in the pilot phase of the study, out of which nine participants exited the study early on the grounds of lack of familiarity with the concept of ACP; hence, 13 responses were analysed, and reported figures are out of a total of 13.

The mean age of the pilot phase participants was 44.2 (±7.9) years, eight out of 13 male and five female. Five were Hindu, 7 Muslim, and 2 Christian. The 13 respondents received their undergraduate medical education in India (4), Sri Lanka (1), Egypt (1), Sudan (4), Nigeria (2) and Kuwait (1).

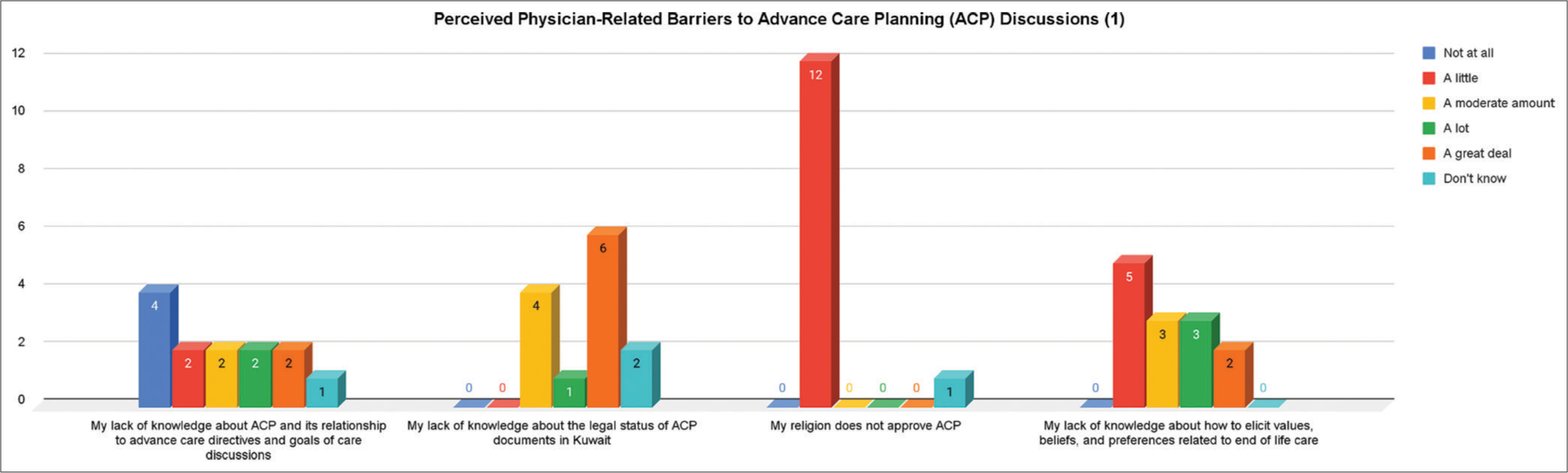

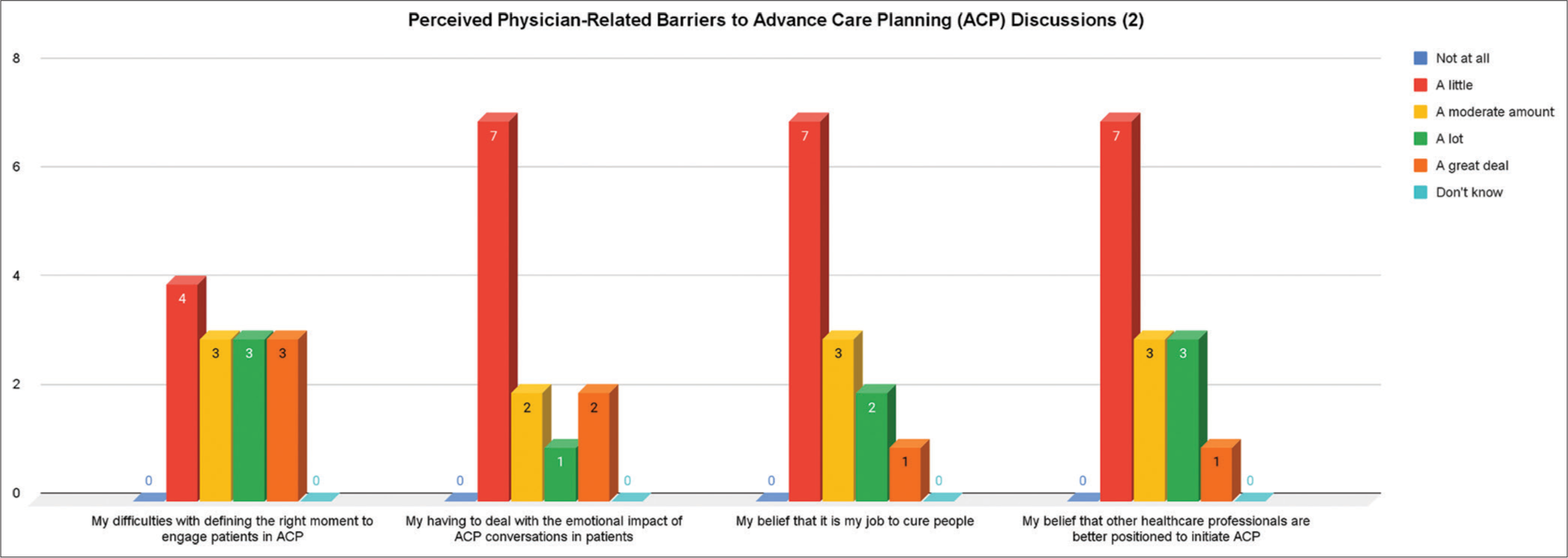

Perceived barriers to initiating ACP discussionsReported perceived barriers to initiating ACP discussions [Figure 1] included lack of knowledge about ACP and its relationship to advance care directives and goals of care discussions (8 out of 13), lack of knowledge about the legal status of ACP documents in Kuwait (11 out of 13), religious disapproval (12 out of 13) and lack of knowledge about how to elicit values, beliefs, preferences related to end of life care (13 out of 13), difficulties with defining the right moment to engage patients in ACP (13 out of 13), having to deal with the emotional impact of ACP conversations in patients (13 out of 13), the belief that it is their job to cure people (13 out of 13), belief that other health-care professionals are better positioned to initiate ACP (13 out of 13) and belief that patients should initiate this type of discussion (13 out of 13).

Export to PPT

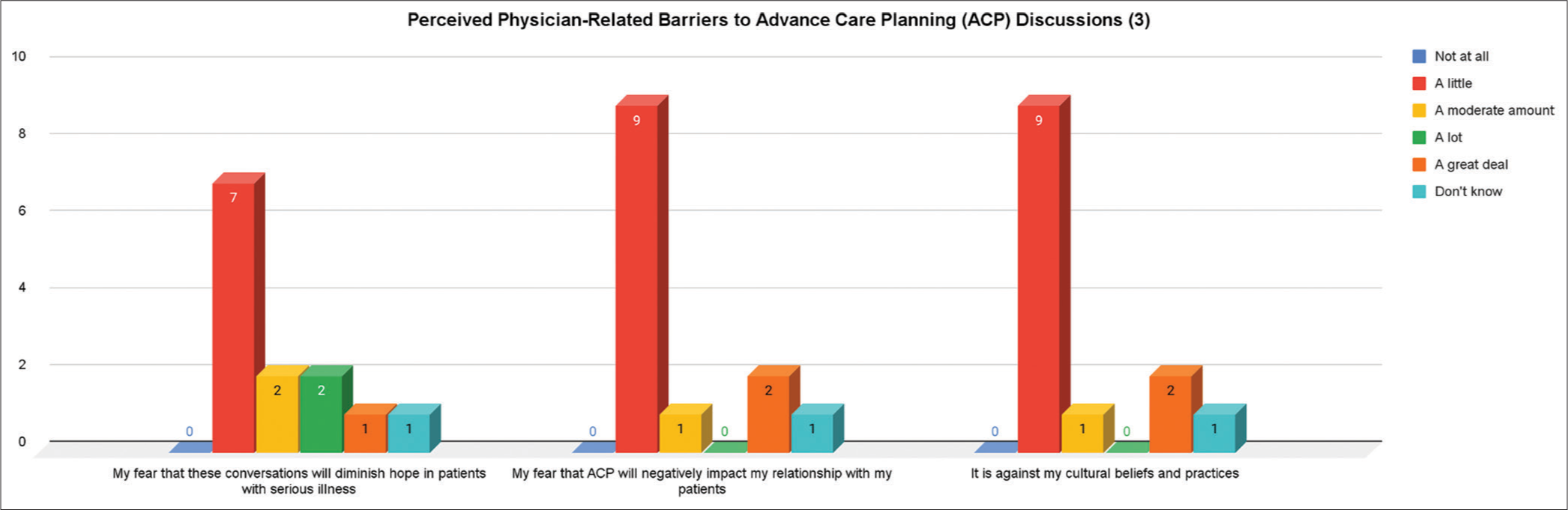

Other reported barriers [Figures 2 and 3] included the fear that these conversations will diminish hope in patients with serious illness (12 out of 13), fear that ACP will negatively impact their relationship with their patients (12 out of 13), and the belief that it is against their cultural beliefs and practices (12 out of 13).

Export to PPT

Export to PPT

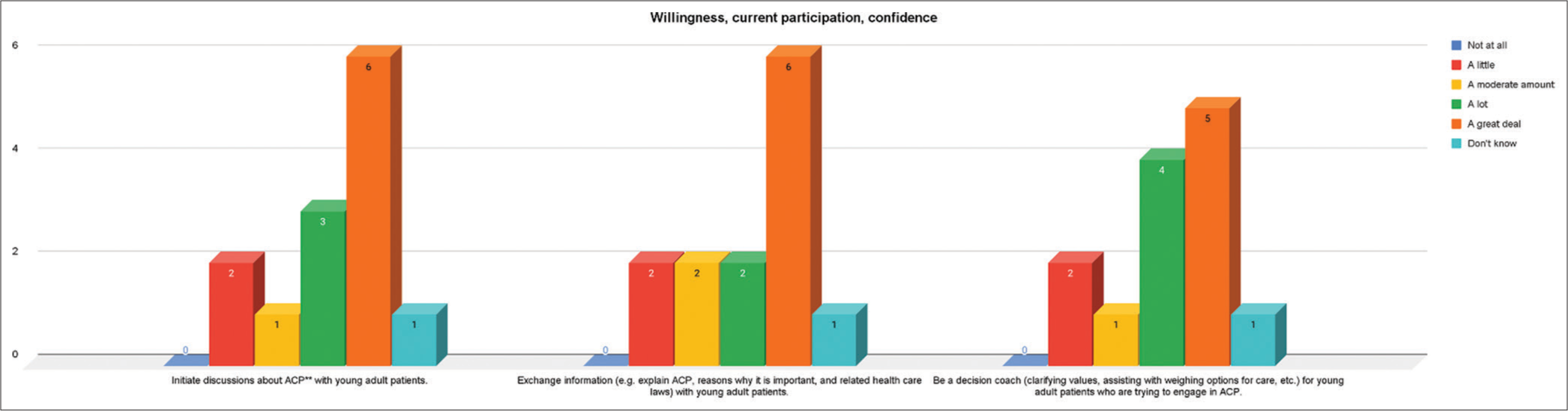

Willingness, current participation, confidenceOut of the 13 participants, 12 were willing to initiate discussions about ACP, 12 were willing to exchange information to explain ACP, reasons why it is important, and related health care laws with young adult patients, while 12 desired to be a decision coach (clarifying values, assisting with weighing options for care, etc.) for young adult patients who are trying to engage in ACP [Figure 4].

Export to PPT

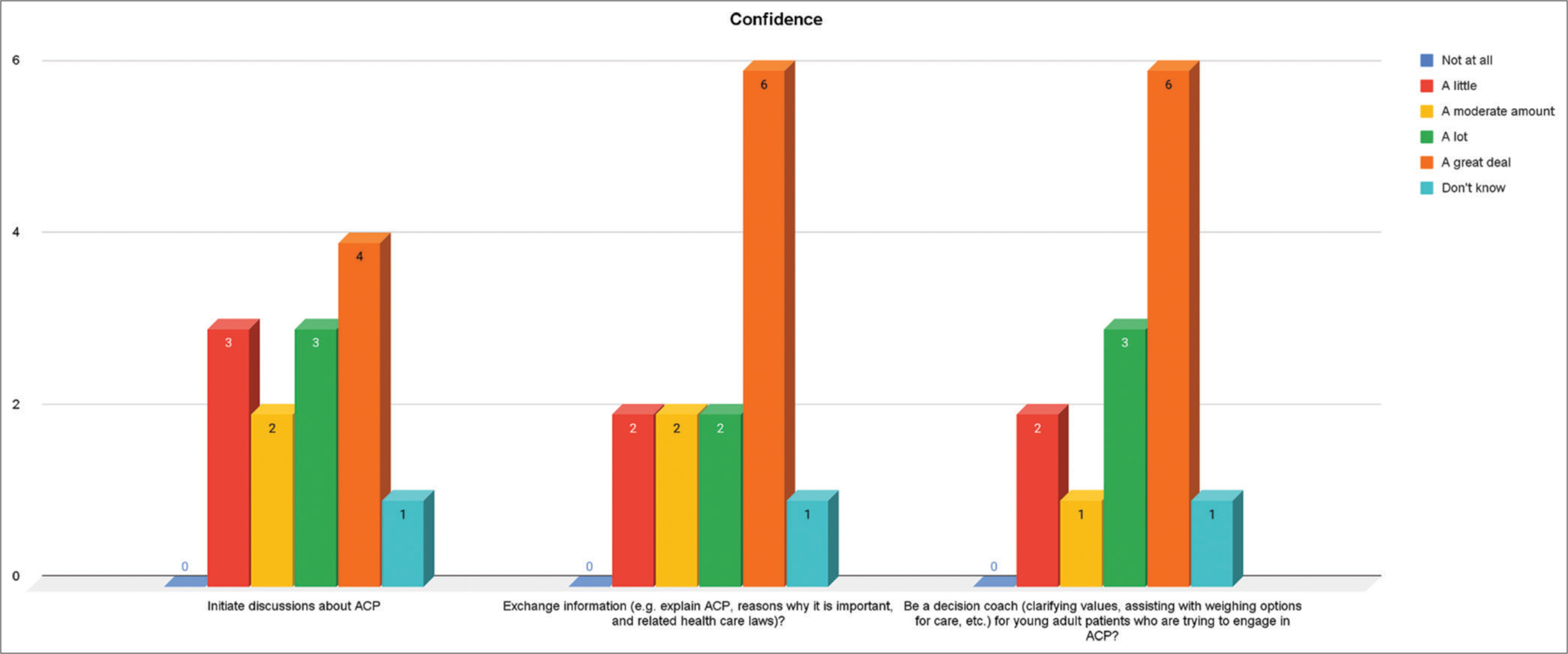

Concerning initiating discussions about ACP with young adults, 12 out of 13 indicated that they were confident, 12 out of 13 were willing to exchange ACP information, and 12 out of 13 were willing to be a decision coach [Figure 5].

Export to PPT

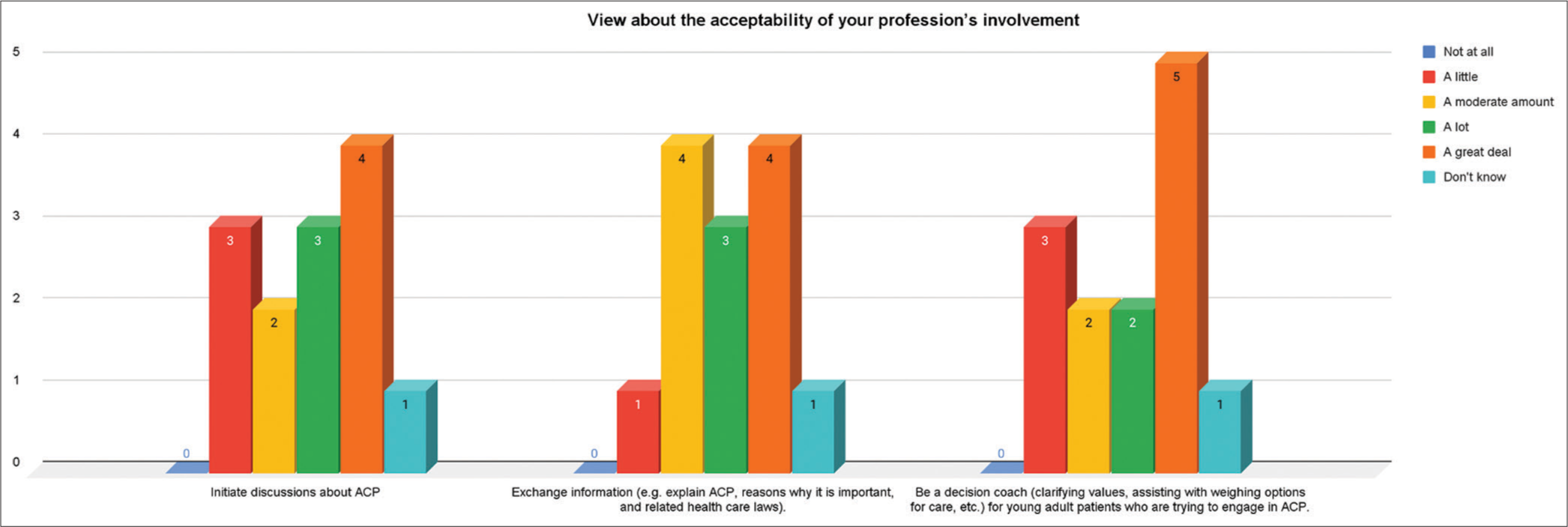

Four out of the 13 participants, respectively, believed that their profession’s involvement in initiating discussions and exchanging information about ACP, while five out of 13 felt a great deal that becoming a decision coach was acceptable [Figure 6].

Export to PPT

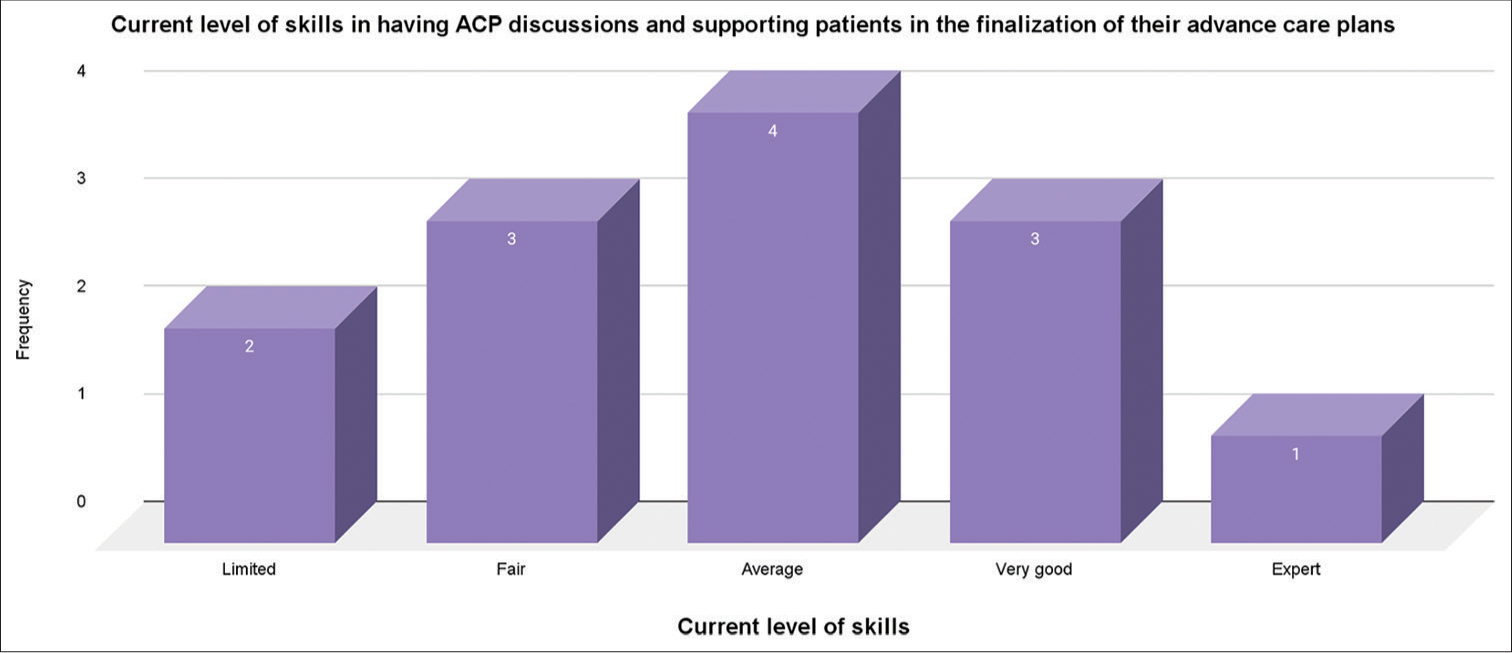

The participants rated their current level of skill in having ACP discussions and supporting patients in the finalisation of their advance care plans as limited (2 out of 13), fair (3 out of 13), average (4 out of 13), very good (3 out of 13) and expert (1 out of 13) [Figure 7].

Export to PPT

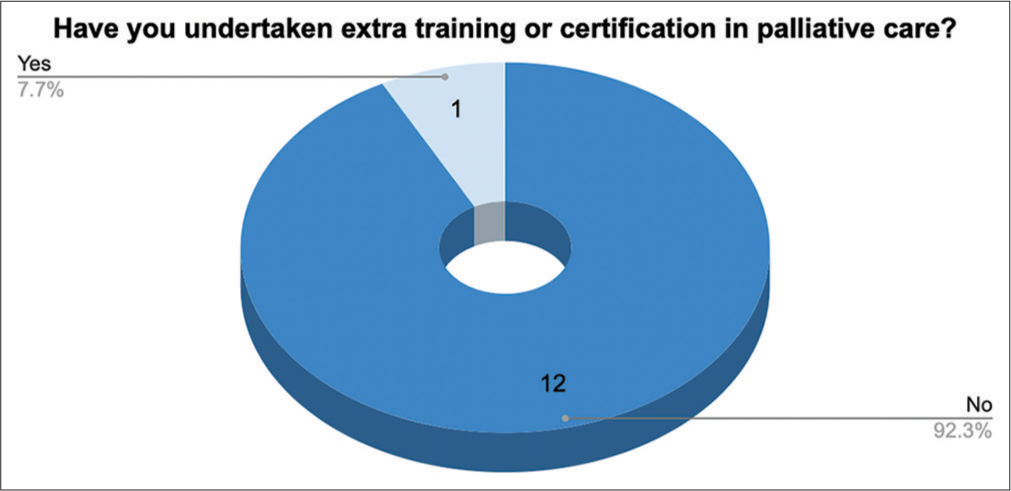

Out of the 13 participating physicians, 12 had yet to take any extra training or certification in ACP, while one out of 13 had done so. When asked if they had a particular interest in palliative care in their practice, seven out of 13 indicated yes, four out of 13 indicated maybe, and two indicated no. Priority for acquiring the skill of ACP was indicated as between moderate (8 out of 13) and high (5 out of 13) [Figure 8].

Export to PPT

DISCUSSIONExisting evidence indicates a low level of engagement despite an expression of willingness of primary care physicians to participate in ACP.[20,31,32] The literature supports the present findings that demonstrated a gap between willingness and practice of ACP, probably attributable to the participants’ low awareness of the concept of ACP. The reported low awareness of ACP might result from the reported lack of training and the reported low engagement in ACP activities.

The reported perceived barriers to ACP activities by the study participants are corroborated by Hafid et al.,[33] whose quality improvement project conducted among primary care physicians and family medicine residents, among others, suggested that barriers to ACP in primary care include logistical challenges such as busy clinical schedules, patient preparedness, provider discomfort and lack of confidence. However, despite the perceived barriers hindering engagement in ACP and the reported lack of training, the participants indicated willingness. They affirmed confidence about initiating discussions, exchanging information, and being decision coaches for young adult patients trying to engage in ACP. This is a crucial call for institutions to utilise available opportunities to train and support primary care physicians and other providers to improve confidence and participation in ACP discussions.[31-33]

According to Silvester and Detering,[34] ACP involving patients and their families is essential for respecting autonomy and dignity and ensuring appropriate care for the elderly and end-of-life. Schichtel et al.[35] also reported that patient-mediated interventions, reminder systems and educational meetings are the most effective in engaging clinicians in ACP for heart failure patients. Zadeh et al.[36] also assessed adolescents and young adults’ interest in endof-life planning, which led to the development of their ACP guide, Voicing My CHOiCES™, and observed that adolescents and young adults are willing to discuss end-of-life issues with their healthcare providers. However, it was asserted that the successful use of their guide will depend on the comfort and skill of the healthcare provider.[36] However, physicians often miss opportunities to engage in ACP discussions during outpatient clinic visits, highlighting the need for communication training to identify patient openers and encourage appropriate responses.[26] Zadeh et al.[36] also assessed adolescents’ and young adults’ interest in end-of-life planning. They observed that adolescents and young adults are willing to discuss end-of-life issues with their healthcare providers. Findings from their study led to the development of their advanced care planning guide, Voicing My CHOiCES™, about which it was asserted that successful use will depend on the comfort and skill of the healthcare provider.[36]

Advanced care planning improves decision-making and reduces decisional conflict in advanced heart failure patients, but more work is needed to implement it effectively.[37] The patient-centered ACP interview effectively promoted shared decision-making, increased satisfaction, and reduced decisional conflict in patients with chronic illnesses and their surrogates.[38] In a related study on heart failure patients, Schichtel et al.[39] revealed that training healthcare professionals in ACP and enabling patients to initiate conversations can help overcome barriers and facilitate engagement in ACP.

Limitations of the studyA major limitation of the study was the low participation rate due to the lack of willingness of potential participants who declined their involvement. A larger sample may have expanded the outcome. Nonetheless, this pilot study has offered insight into potential barriers to advanced care planning, especially in rarely emphasised situations such as the management of young adults living with cardiometabolic diseases.

CONCLUSIONDespite the low level of awareness and other factors perceived as barriers, primary care physicians are confident and willing to initiate ACP discussions with young adults living with cardiometabolic diseases. ACP was reported to improve decision-making and reduce decisional conflict at the end-of-life period. The study revealed physicians’ perceived barriers and willingness to initiate ACP as part of the holistic care for young adult patients. Coordinated efforts should be made to develop the knowledge and skills of primary care physicians who have never had training in advanced care planning so that the existing gap between willingness and practice of ACP can be reduced or eradicated.

留言 (0)