Type D personality describes the personality characteristics of individuals prone to psychological stress and has two substructures: negative affect and social inhibition (1). While negative affect is characterized by the predominance and longer duration of unwanted negative emotions, social inhibition represents the reduction of social interaction and suppression of the expression of emotions (2). It has been reported that individuals with Type D personality may have a more depressed and dysphoric affect and have anxiety about rejection and disapproval from others (3, 4). Some studies have shown that individuals with Type D personality may be more prone to both stress-related physical problems such as cardiovascular diseases and psychological problems such as depression, burnout, and anxiety disorders (5–10).

Job satisfaction is defined as the individual’s positive feelings about his or her profession or job, as well as his or her evaluation of how the profession or job meets the individual’s needs, desires, and expectations (11). Job satisfaction can be affected by individual and job-related variables. Many studies have shown that job satisfaction can be affected by factors related to the job performed. For example, it is known that working hours, income, supervision, career goals, and relationships in the work environment have an impact on job satisfaction (12–15).

On the other hand, job satisfaction may also be affected by individual characteristics. For example, it has been reported that personality structure or characteristics may affect job satisfaction (16, 17). Personality-specific traits such as extraversion, introversion, and neuroticism have an impact on an individual’s job satisfaction (18, 19). The hypothesis that the type D personality structure may negatively affect job satisfaction due to its main components (NA and SI) has been investigated in some employee groups other than teachers. It has been found that healthcare professionals with a Type D personality have lower job satisfaction than those without a Type D personality, and Type D personality may negatively affect the job satisfaction of nurses (20, 21).

One of the important factors affecting job satisfaction is the psychological problems of the individual. Many studies have shown that psychological factors such as depression, high-stress levels, anxiety disorders, burnout, and sleep problems can negatively affect an individual’s job satisfaction (22–26). Depression is one of the most common mental problems in the world and one that causes the most disability (27). Depression, which is characterized by symptoms such as anhedonia, loss of interest, depressed mood, sleep-appetite problems, loss of energy, and beliefs of worthlessness or low self-esteem, suicidal ideations, has been reported as a factor that negatively affects job satisfaction in many professional groups (28–30). Research in different occupational groups has shown that core symptoms of depression, such as anhedonia, loss of interest, and depressed mood, can reduce job satisfaction (31). It is also known that depressive symptoms can negatively affect job satisfaction in teachers, who are one of the professional groups that work in direct interaction with people (32, 33).

Based on all the information highlighted above, it is clear that there is a relationship between depressive complaints and job satisfaction. On the other hand, it can be said that type D personality, which is characterized by negative affect and social suppression, increases the tendency to some psychological problems such as depressive symptoms, burnout, and anxiety. It can be said that the type D personality structure has components that can affect both the emergence of depressive symptoms and job satisfaction and thus may play a role in the relationship between depressive symptoms and job satisfaction. To our knowledge, there is no research examining the moderating role of Type D personality structure between depressive symptom severity and job satisfaction. The main hypothesis of this study is that the Type D personality structure may have a regulatory function between depressive complaints and job satisfaction due to its defining characteristics (NA and SI). The aim of this study is to investigate the moderating role of Type D personality structure between the severity of depressive symptoms and job satisfaction in teachers.

Materials and methods ParticipantsThe present study had a cross-sectional and descriptive nature. The sample of the research consisted of 939 teachers working in 73 public schools in Van Province and voluntarily filling out the online survey sent with the permission of the Directorate of National Education. 63 of the participants (6.7%) were preschool teachers, 544 were primary school teachers (57.9%), and 332 were high school teachers (35.4%). 761 of the teachers (81%) were working in schools in the city and district centers, and 178 (19%) were working in village schools. The inclusion criteria for the study were being an active teacher, not having a serious psychiatric disease (such as schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, or substance use disorder), and being a volunteer. All stages of the study were approved by the Van Education and Research Hospital Ethics Committee (2022/07–02), and permission was obtained from the National Education Directorates for the study (Permission Number: 49492119). It ensured that there was a research process in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and research in humans. The ethics committee legally monitored the online interview technique, data collection, and confidentiality of participants’ data. The consent of the participants was obtained in the online survey application. The first screen of the online survey explained the purpose of the study and asked whether the participant would like to participate in the study voluntarily. The participants who wanted to participate in the research voluntarily could access the next forms only after pressing the approval button.

Material Sociodemographic formThis form includes participants’ characteristics such as age, gender, marital status, income level, working years, and weekly working hours.

Type D personality scale (DS-14)It is a Likert-type self-report scale consisting of 14 items developed by Denollet (2). The scale consists of two subscales: negative affect and social inhibition. Each item is scored between 0 and 4. While the scores that can be calculated from the subscales (NA and SI) vary between 0 and 28 points, the total score of the scale varies between 0 and 56. Increasing scores from the subscales means that Type D personality traits also increase. Turkish validity and reliability study was conducted by Alçelik et al. (34). Internal consistency coefficients for the Turkish form of the scale are 0.82 for NA and 0.81 for SI.

Minnesota satisfaction scale short form (MSS-SF)It is a Likert-type self-report scale consisting of 20 items developed by Weiss et al. (35). The scale consists of two subscales: intrinsic satisfaction and extrinsic satisfaction. Intrinsic satisfaction consists of factors related to satisfaction with the internal nature of the job, such as success, recognition or acceptance, job responsibility, and change of duties due to promotion. Extrinsic satisfaction consists of elements related to the business environment, such as business dynamics, control style, relations with the manager, work and subordinates, working conditions, and wages. Each item varies between 1 and 5 points. The scale has 12 items that evaluate intrinsic satisfaction and 8 items that evaluate extrinsic satisfaction. As the scores from the subscales increase, job satisfaction also increases. Turkish validity and reliability study was conducted by Baycan (36). In the Turkish validity and reliability study of the scale, the Cronbach’s alpha value was found to be 0.77.

Statistical analysisSPSS 25.0 package program and Jamovi 2.4.14 statistical program were used for statistical analysis of the data. Sociodemographic characteristics and the scale scores of the participants were calculated as mean, standard deviation, number and percentage. Normality distribution of continuous variables was examined with the Kolmogorov Smirnov test. Pearson’s correlation test was used to evaluate the relationship between BDI, MSS-SF, and DS-14 scales scores. The role of NA and SI between BDI, and IS and ES was investigated by moderator analysis. Harman’s single-factor test was used to evaluate common method variance bias, and all self-report scale scores used in the study were subjected to non-rotation factor analysis (When the number of factors is limited to 1, the total variance explained is 32.70%, and if the rate was lower than 50%, it was interpreted that there was no common method variance error in the study). Bonferroni’s correction was used in multiple comparisons in order to minimize the risk of type I error. In all analyses, the significance level was accepted as p < 0.05.

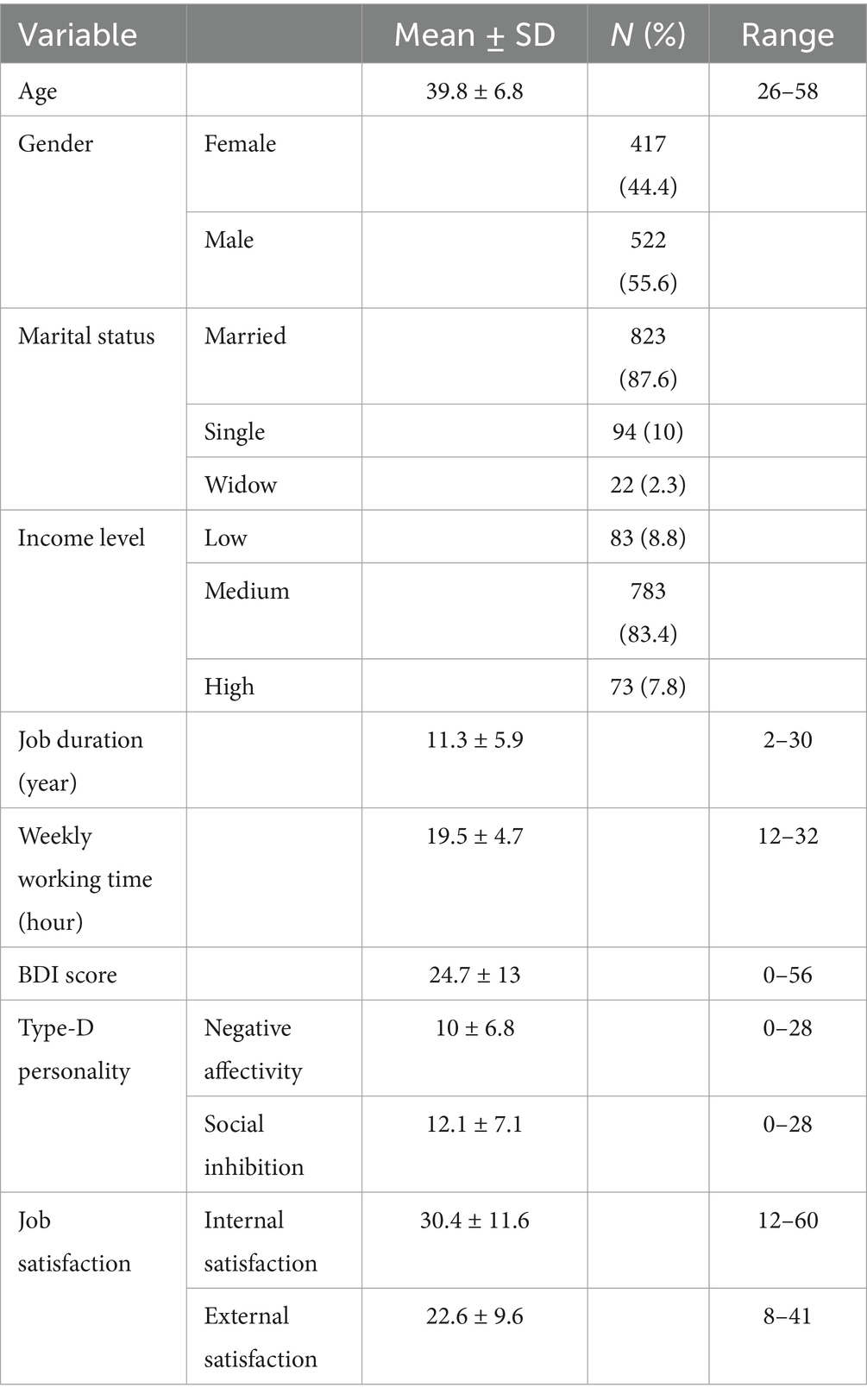

ResultsThe mean age of the teachers was 39.8 ± 6.8 years (Range of age = 26–58 years). 55.6% (n = 522) of the teachers were male and 44.4% (n = 417) were female. The sociodemographic characteristics and scale scores of the participants were shown in Table 1.

Table 1. Characteristics of the teachers.

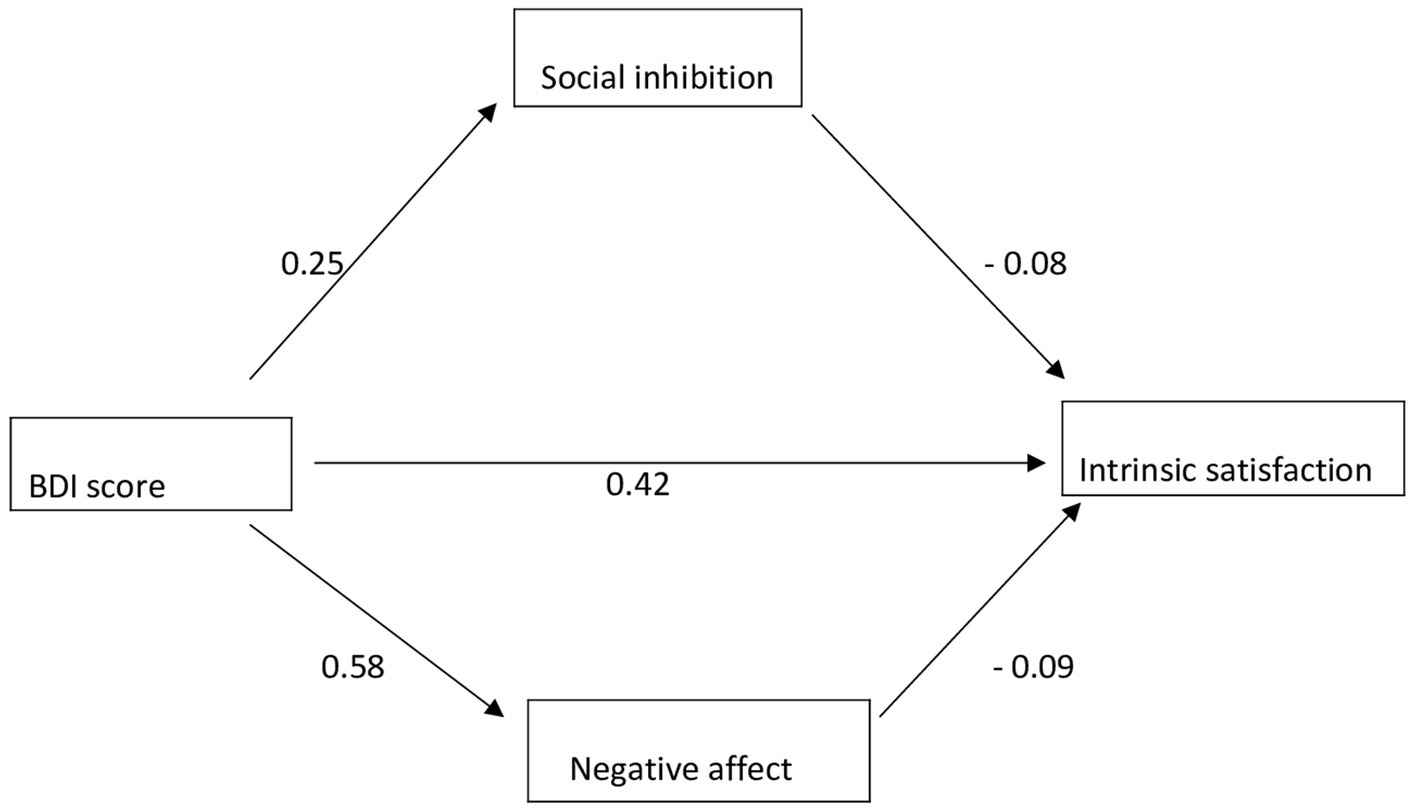

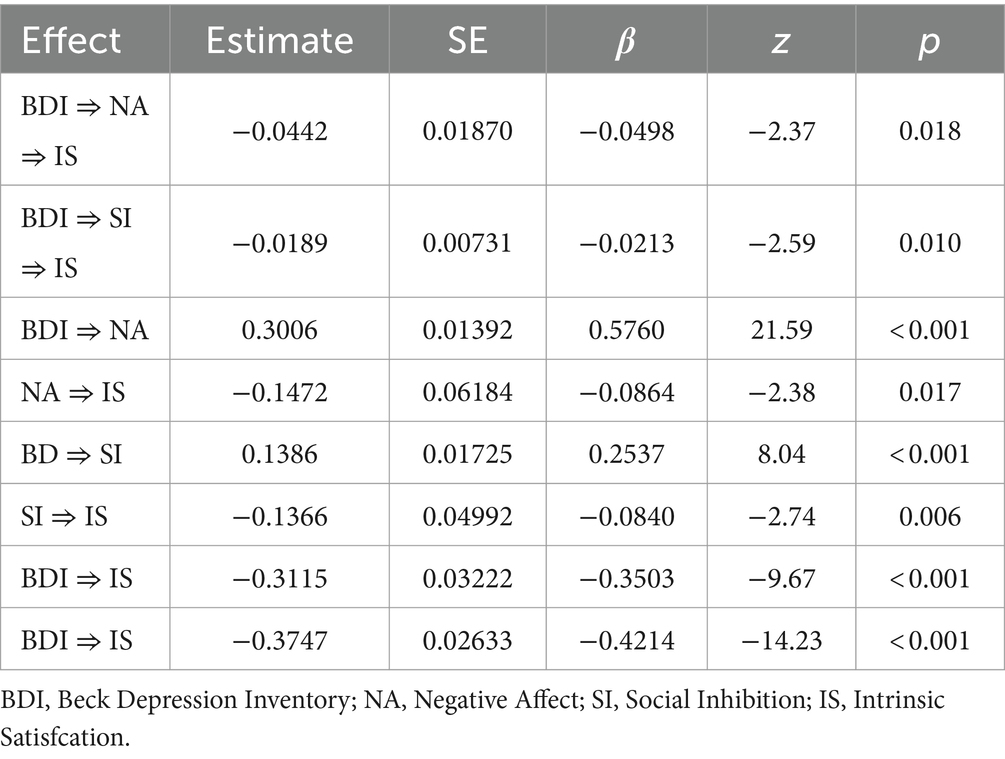

According to the moderation relationship carried out for the intrinsic satisfaction sub-dimension of job satisfaction, the indirect effect is negative affect (β =0.049, SE = 0.018, p < 0.001) and social inhibition (β =0.021, SE = 0.007, p < 0.001). And total effect (β =0.421, SE = 0.026, p < 0.001) results are significant. Although the direct effect result was significant (β =0.350, SE = 0.032, p < 0.001), the effect level decreased when compared to the total effect when the moderator variable was included in the model. This result shows that negative affect and social inhibition have a partial moderating role in the relationship between depression and intrinsic job satisfaction. The results are in Figure 1 and Table 2.

Figure 1. Moderator variable analysis for intrinsic satisfaction.

Table 2. Moderator variable analysis results for intrinsic satisfaction.

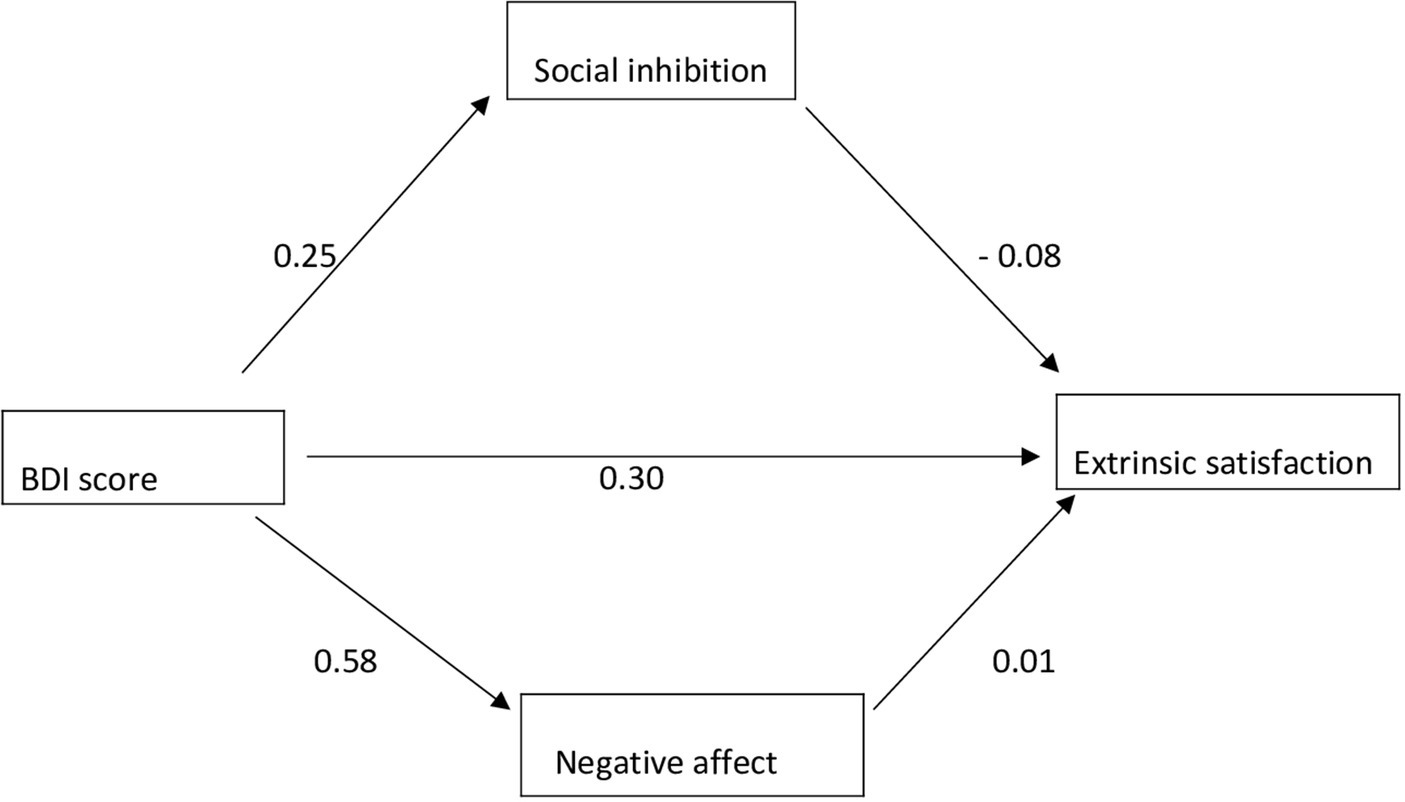

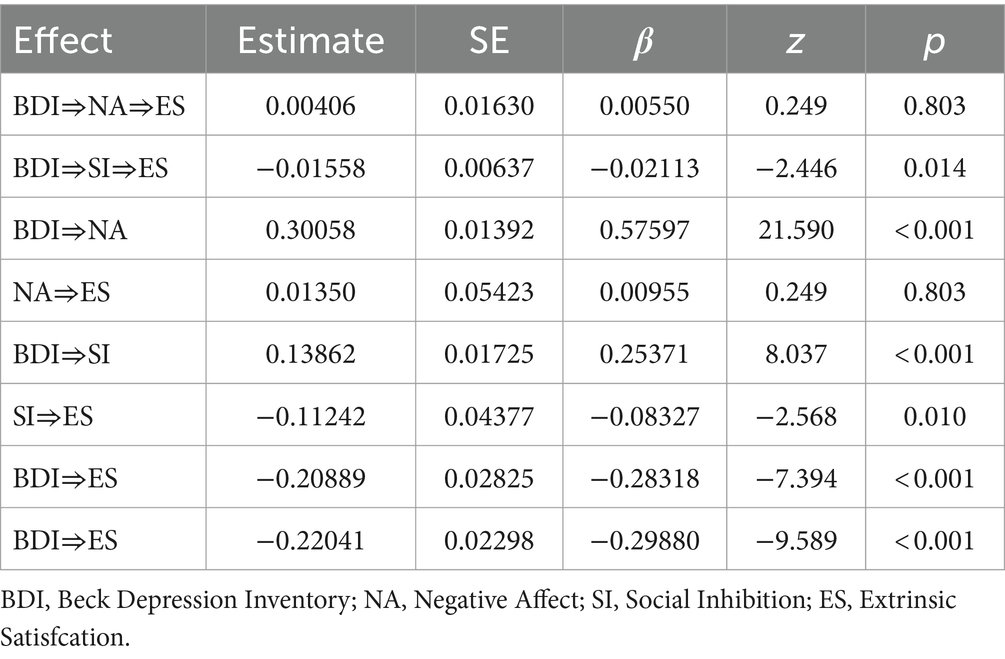

According to the moderation relationship conducted for the extrinsic satisfaction sub-dimension of job satisfaction, social inhibition (β = 0.083, SE = 0.043, p < 0.05) and total effect (β =0.298, SE = 0.022, p < 0.001) are the indirect effects. While the results were significant, negative affect (β = 0.009, SE = 0.005, p > 0.05) was found to have no significant effect. Although the direct effect result was significant (β = 0.283, SE = 0.022, p < 0.001), the effect level decreased when compared to the total effect when the moderator variable was included in the model. This result shows that social inhibition plays a partial moderating role in the relationship between depression and intrinsic job satisfaction, while negative affect has no role. The results are in Figure 2 and Table 3.

Figure 2. Moderator variable analysis for extrinsic satisfaction.

Table 3. Moderator variable analysis results for extrinsic satisfaction.

DiscussionThe aim of this study is to investigate the moderating role of Type D personality traits (NA and SI) between the severity of depressive complaints and job satisfaction of teachers working in public schools in Turkey. To our knowledge, our study is the first to investigate the moderating role of Type D personality traits in the relationship between depressive symptoms severity and job satisfaction. According to the findings of the present study, NA and SI in the teachers have a partial moderator role between the severity of depressive complaints and intrinsic job satisfaction, and SI have a partial moderator role between the severity of depressive complaints and extrinsic satisfaction.

Many studies have reported that job satisfaction is negatively affected by psychological complaints such as depression. There are also publications showing that increasing severity of depressive complaints among teachers is associated with a decrease in job satisfaction. It is known that both the core symptoms of depression, such as anhedonia, depressed mood, and decreased self-esteem, and the vegetative symptoms (such as a decrease in sleep and energy) affect job satisfaction in teachers (32, 33, 37–40). The findings of the present study have shown that increased depressive symptom levels are correlated with lower intrinsic and extrinsic job satisfaction in the teachers. It can be said that the findings of our study are consistent with the findings of previous studies in this aspect. Of course, there may be other confounding factors that may affect the emergence of depressive complaints and job satisfaction in teachers. Therefore, future studies may help reinterpret other psychosocial factors that may cause depressive complaints in teachers and thus affect job satisfaction.

The findings of some studies have shown that personality traits are also one of the factors affecting job satisfaction. For example, there is evidence showing that job satisfaction is higher in teachers who are extroverted or have high self-efficacy (41, 42). On the other hand, it has been reported that job satisfaction is lower in teachers with predominant neurotic traits, who tend to express more negative affect (43, 44). The findings of this study showed that teachers with high negative affect and social suppression characteristics had lower job satisfaction.

Although there is no study in the literature investigating the role of type D personality structure between depression and job satisfaction, it is known that individuals with type D personality structure are more prone to depressive symptoms. For example, individuals with type D personality structure have been reported to have more suicidal thoughts along with depressive complaints (45). On the other hand, negative affect or introverted personality traits have been shown to be associated with low job satisfaction (18, 46, 47). The findings of the present study have shown that NA and SI may have a partial moderating role between depressive symptoms and internal job satisfaction. In other words, it can be said that negative affect and social inhibition play a role between depressive symptom severity and intrinsic satisfaction elements such as perception of success and recognition-appreciation. We thought that teachers with predominant negative affect and social inhibition traits might have lower intrinsic job satisfaction, related to lower self-efficacy or a more severe perception of job stress. As a matter of fact, it has been shown that type D personality structure in nurses may reduce job satisfaction due to perceived high job stress and burnout (48). In another study, type D personality was found to be associated with low self-resilience and self-esteem in nursing students (49).

Another important finding of our study is that SI has a partial moderator role between the severity of teachers’ depressive complaints and extrinsic job satisfaction. Accordingly, it can be said that social inhibition has a role between the severity of depressive complaints in teachers and extrinsic job satisfaction elements such as superior-subordinate relationship dynamics and adaptation to work conditions. In our opinion, SI characteristics of teachers who are introverts and have less social participation may be more dominant, and SI may be an important moderator between these teachers’ extrinsic job satisfaction and the severity of depressive complaints. As a matter of fact, it has been reported that low social interaction is associated with low job satisfaction (49, 50).

Although it has strengths such as having a relatively large sample size and being the first study to investigate the relationship between the type D personality structure and the severity of depressive complaints and job satisfaction, our study has some limitations. First of all, the findings are not definitive due to the cross-sectional nature of the study. The fact that the sample of the study consisted of teachers in only one city did not allow interpreting the results that could be affected by possible sociocultural differences. Additionally, the fact that all data were obtained from self-report scales can be considered a limitation.

ConclusionIn conclusion, our findings show that the negative affect and social inhibition traits of the Type D personality structure have a moderating role between the severity of depressive complaints and job satisfaction in teachers. Training and support programs to recognize personality traits in teachers and professional psychosocial intervention programs can help increase job satisfaction. Future studies may help to understand how recognition of personality traits in teachers and professional support programs may affect job satisfaction.

Data availability statementThe raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statementThe studies involving humans were approved by Van Education Research Hospital, Ethic Committee. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributionsAY: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Resources, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. HK: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

FundingThe author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

AcknowledgmentsThe authors would like to thank Şeyma Sevgican, a lecturer in the Department of Psychology at Hasan Kalyoncu University, Gaziantep, Turkey for her support in statistical analysis.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's noteAll claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References1. Denollet, J. Type D personality. A potential risk factor refined. J Psychosom Res. (2000) 49:255–66. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3999(00)00177-x

Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

2. Denollet, J. DS14: standard assessment of negative affectivity, social inhibition, and Type D personality. Psychosom Med. (2005) 67:89–97. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000149256.81953.49

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

3. Polman, R, Borkoles, E, and Nicholls, AR. Type D personality, stress, and symptoms of burnout: the influence of avoidance coping and social support. Br J Health Psychol. (2010) 15:681–96. doi: 10.1348/135910709X479069

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

4. De Fruyt, F, and Denollet, J. Type D personality: a five-factor model perspective. Psychol Health. (2002) 17:671–83. doi: 10.1080/08870440290025858

Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

5. Raykh, OI, Sumin, AN, and Korok, EV. The influence of personality Type D on cardiovascular prognosis in patients after coronary artery bypass grafting: data from a 5-year-follow-up study. Int J Behav Med. (2022) 29:46–56. doi: 10.1007/s12529-021-09992-y

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

6. Denollet, J, Trompetter, HR, and Kupper, N. A review and conceptual model of the association of Type D personality with suicide risk. J Psychiatr Res. (2021) 138:291–300. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2021.03.056

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

7. Whittaker, AC, Ginty, A, Hughes, BM, Steptoe, A, and Lovallo, WR. Cardiovascular stress reactivity and health: recent questions and future directions. Psychosom Med. (2021) 83:756–66. doi: 10.1097/psy.0000000000000973

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

8. Kupper, N, and Denollet, J. Type D personality as a risk factor in coronary heart disease: a review of current evidence. Curr Cardiol Rep. (2018) 20:104. doi: 10.1007/s11886-018-1048-x

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

9. Laoufi, MA, Wacquier, B, Lartigolle, T, Loas, G, and Hein, M. Suicidal ideation in major depressed individuals: role of Type D personality. J Clin Med. (2022) 11:6611. doi: 10.3390/jcm11226611

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

10. Tekin, A, Karadağ, H, and Yayla, S. The relationship between burnout symptoms and Type D personality among health care professionals in Turkey. Arch Environ Occup Health. (2017) 72:173–7. doi: 10.1080/19338244.2016.1179168

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

11. Mueller, CW, and McCloskey, JC. Nurses' job satisfaction: a proposed measure. Nurs Res. (1990) 39:116–7. doi: 10.1097/00006199-199003000-00014

Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

12. Fisher, CD. Why do lay people believe that satisfaction and performance are correlated? Possible sources of a commonsense theory. J Organ Behav. (2003) 24:753–77. doi: 10.1002/job.219

Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

13. Arian, M, Soleimani, M, and Oghazian, MB. Job satisfaction and the factors affecting satisfaction in nurse educators: a systematic review. J Prof Nurs. (2018) 34:389–99. doi: 10.1016/j.profnurs.2018.07.004

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

14. Yasin, YM, Kerr, MS, Wong, CA, and Bélanger, CH. Factors affecting nurses' job satisfaction in rural and urban acute care settings: a PRISMA systematic review. J Adv Nurs. (2020) 76:963–79. doi: 10.1111/jan.14293

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

15. Anastasiou, S, and Papakonstantinou, G. Factors affecting job satisfaction, stress and work performance of secondary education teachers in Epirus. Int J Manag Educ. (2014) 8:37–53. doi: 10.1504/IJMIE.2014.058750

Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

16. Wang, H, and Lei, L. Proactive personality and job satisfaction: social support and Hope as mediators. Curr Psychol. (2023) 42:126–35. doi: 10.1007/s12144-021-01379-2

Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

17. Topino, E, Di Fabio, A, Palazzeschi, L, and Gori, A. Personality traits, workers' age, and job satisfaction: the moderated effect of conscientiousness. PLoS One. (2021) 16:e0252275. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0252275

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

18. Petasis, A, and Economides, O. The big five personality traits, occupational stress, and job satisfaction. Eur J Bus Manag Res. (2020) 5:410. doi: 10.24018/ejbmr.2020.5.4.410

Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

19. Sowunmi, OA. Job satisfaction, personality traits, and its impact on motivation among mental health workers. S Afr J Psychiatry. (2022) 28:1801. doi: 10.4102/sajpsychiatry.v28i0.1801

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

20. Nah-Mee, S, and Ha, KY. Health promotion behaviors, subjective health status, and job satisfaction in shift work nurses based on Type D personality pattern. J Korean Acad Nurs Adm. (2021) 27:12–20. doi: 10.11111/jkana.2021.27.1.12

Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

21. Kim, YH, Kim, SR, Kim, YO, Kim, JY, Kim, HK, and Kim, HY. Influence of type D personality on job stress and job satisfaction in clinical nurses: the mediating effects of compassion fatigue, burnout, and compassion satisfaction. J Adv Nurs. (2017) 73:905–16. doi: 10.1111/jan.13177

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

22. Hünefeld, L, Gerstenberg, S, and Hüffmeier, J. Job satisfaction and mental health of temporary agency workers in Europe: a systematic review and research agenda. Work Stress. (2020) 34:82–110. doi: 10.1080/02678373.2019.1567619

Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

23. Bagheri, HAM, Taban, E, Khanjani, N, Naghavi Konjin, Z, Khajehnasiri, F, and Samaei, SE. Relationships between job satisfaction and job demand, job control, social support, and depression in Iranian nurses. J Nurs Res. (2020) 29:e143. doi: 10.1097/jnr.0000000000000410

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

24. Cubbon, L, Darga, K, Wisnesky, UD, Dennett, L, and Guptill, C. Depression among entrepreneurs: a scoping review. Small Bus Econ. (2021) 57:781–805. doi: 10.1007/s11187-020-00382-4

Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

25. Schonfeld, IS, and Bianchi, R. From burnout to occupational depression: recent developments in research on job-related distress and occupational health. Front Public Health. (2021) 9:796401. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2021.796401

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

26. Yehya, A, Sankaranarayanan, A, Alkhal, A, Alnoimi, H, Almeer, N, Khan, A, et al. Job satisfaction and stress among healthcare workers in public hospitals in Qatar. Arch Environ Occup Health. (2020) 75:10–7. doi: 10.1080/19338244.2018.1531817

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

27. König, H, König, HH, and Konnopka, A. The excess costs of depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Epidemiol Psychiatr Sci. (2020) 29:e30–16. doi: 10.1017/S2045796019000180

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

28. Zhdanava, M, Pilon, D, Ghelerter, I, Chow, W, Joshi, K, Lefebvre, P, et al. The prevalence and national burden of treatment-resistant depression and major depressive disorder in the United States. J Clin Psychiatry. (2021) 82:29169. doi: 10.4088/JCP.20m13699

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

30. Meier, ST, and Kim, S. Meta-regression analyses of relationships between burnout and depression with sampling and measurement methodological moderators. J Occup Health Psychol. (2022) 27:195. doi: 10.1037/ocp0000273

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

31. Villarreal-Zegarra, D, Lázaro-Illatopa, WI, Castillo-Blanco, R, Cabieses, B, Blukacz, A, Bellido-Boza, L, et al. Relationship between job satisfaction, burnout syndrome and depressive symptoms in physicians: a cross-sectional study based on the employment demand–control model using structural equation modelling. BMJ Open. (2022) 12:e057888. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2021-057888

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

32. Agyapong, B, Obuobi-Donkor, G, Burback, L, and Wei, Y. Stress, burnout, anxiety and depression among teachers: a scoping review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2022) 19:10706. doi: 10.3390/ijerph191710706

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

33. Capone, V, and Petrillo, G. Mental health in teachers: relationships with job satisfaction, efficacy beliefs, burnout and depression. Curr Psychol. (2020) 39:1757–66. doi: 10.1007/s12144-018-9878-7

Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

34. Alçelik, A, Yildirim, O, Canan, F, Eroglu, M, Aktas, G, and Savli, H. A preliminary psychometric evaluation of the type D personality construct in Turkish hemodialysis patients. J Mood Disord. (2012) 2:1–5. doi: 10.5455/jmood.20120307062608

Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

35. Weiss, DJ, Dawis, RV, England, GW, and Lofquist, LH. Minnesota satisfaction questionnaire--short form. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota (1967).

36. Baycan, A. Analysis of several aspects of job satisfaction between different occupational groups. İstanbul: Bogaziçi Üniversitesi Sosyal Bilimler Enstitüsü (1985).

37. Einar, MS, and Skaalvik, S. Teacher burnout: relations between dimensions of burnout, perceived school context, job satisfaction and motivation for teaching. Teach Teach. (2020) 26:602–16. doi: 10.1080/13540602.2021.1913404

Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

38. Méndez, I, Martínez-Ramón, JP, Ruiz-Esteban, C, and García-Fernández, JM. Latent profiles of burnout, self-esteem and depressive symptomatology among teachers. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2020) 17:6760. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17186760

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

39. Ortan, F, Simut, C, and Simut, R. Self-efficacy, job satisfaction and teacher well-being in the K-12 educational system. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2021) 18:12763. doi: 10.3390/ijerph182312763

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

40. Bašković, M, Luetić, F, Fusić, S, Rešić, A, Striber, N, and Šogorić, S. Self-esteem and work-related quality of life: tertiary centre experience. J Health Manag. (2022) 22:09720634221128718. doi: 10.1177/09720634221128

Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

41. Perera, HN, Granziera, H, and McIlveen, P. Profiles of teacher personality and relations with teacher self-efficacy, work engagement, and job satisfaction. Pers Individ Differ. (2018) 120:171–8. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2017.08.034

Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

42. Richter, E, Lucksnat, C, Redding, C, and Richter, D. Retention intention and job satisfaction of alternatively certified teachers in their first year of teaching. Teach Teach Educ. (2022) 114:103704. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2022.103704

Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

43. Li, J, Yao, M, Liu, H, and Zhang, L. Influence of personality on work engagement and job satisfaction among young teachers: mediating role of teaching style. Curr Psychol. (2023) 42:1817–27. doi: 10.1007/s12144-021-01565-2

Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

44. Liu, Z, Li, Y, Zhu, W, He, Y, and Li, D. A meta-analysis of teachers’ job burnout and big five personality traits. Front Educ. (2022) 7:822659. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2022.822659

Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

45. Park, YM, Ko, YH, Lee, MS, Lee, HJ, and Kim, L. Type-d personality can predict suicidality in patients with major depressive disorder. Psychiatry Investig. (2014) 11:232–6. doi: 10.4306/pi.2014.11.3.232

留言 (0)