Autism is a neurodevelopmental disorder characterised by social and communication deficits and restricted or repetitive patterns of behaviour (1), with prevalence currently estimated as one in 100 (2). Aggression is not a core symptom of autism but rates of aggression in autistic children and adolescents range from 25% (3) to 53% (4). This aspect of autism has been growing in interest with research increasingly focusing on the relationship between autism and psychopathy.

Psychopathy is characterised by shallow emotional response, a diminished capacity for empathy or remorse, callousness, and poor behavioural control (5, 6). Prevalence in the general population is estimated at 4.5%, with a higher prevalence among offenders (7). It has long been associated with criminal and violent behaviour and is a key predictor of recidivism (8). Psychopathy can be categorised into primary and secondary psychopathy; primary psychopathy results from largely genetic and biological influences, and secondary psychopathy is related to adverse environmental factors (such as developmental trauma/maltreatment) (9). Primary psychopathy is associated with increased emotionally stability, fearlessness, and being more self-assured than secondary psychopathy, which is often associated with greater psychopathology. As children and young people are still developing, they are not considered capable of presenting with psychopathy; instead, a precursor is observed, referred to as callous and unemotional traits [CUTs; (10)].

Whilst the link between psychopathy and criminality is well evidenced (11), the relationship between autism and criminality is less clear. Collins et al. (12) reported that criminality rates amongst those with autism ranged from 0.2% (13) to 62.8% (14) within their systematic review, indicating an overrepresentation of autism amongst offenders. Despite this, the review suggested that there is little evidence that autistic individuals have an increased risk of committing crimes, highlighting methodological limitations which impacted the reliability of conclusions. It was hypothesised that social communication difficulties may make autistic individuals more likely to be viewed as risky, encounter the criminal justice system, and receive custodial sentences.

1.2 The role of empathyAutism and psychopathy are both characterised by empathic dysfunction which plays a role in their behavioural phenotypes, and whilst they may appear to share surface similarities, the underlying difficulties may differ (15). Empathy involves understanding and sharing others’ emotions, thoughts or feelings and can be divided into cognitive (understanding thoughts and feelings) and affective (sharing emotional experiences) empathy (15). It has been proposed that autistic people struggle with cognitive empathy but not affective empathy, whereas the opposite is found within psychopathy (16–18).

Cognitive empathy requires theory of mind (ToM)/perspective taking skills, and together with affective empathy both are required when making moral decisions (19). Autistic people who have difficulties with cognitive empathy may inadvertently cause harm to others due to difficulty interpreting the behaviour of others (20), while individuals with psychopathy are more likely to engage in criminality and have difficulties with affective empathy and emotion recognition, but present with intact ToM skills (15, 21). Those with psychopathy are thought to have difficulties with recognising aversive emotions in others (e.g., fear and sadness) resulting from deficits in amygdala and orbital/ventrolateral frontal cortex function (22) and these difficulties interfere with learning and subsequent avoidance. For example, fearfulness is aversive, and if attenuated, an individual may behave in self-gratifying manner without concern about the consequence as they experience no fear of negative consequences for themselves or others. There is also evidence of difficulties with recognising non-aversive emotions (23) which may be related to difficulties with attention allocation to the eyes of others (24). Diminished affective empathy, paired with the ability to mentalise, enables psychopaths to successfully manipulate others for personal gain (15). This contrasts with autistic individuals who experience aversive emotions if they believe they have caused harm (20). Therefore, although both autism and psychopathy are characterised by empathic dysfunction, behaviour and decision-making are very different and driven by distinct empathetic pathways.

1.3 Aims and rationaleLittle is known about the co-existence of autism and psychopathy. Rogers et al. (25), proposed the ‘double hit’ hypothesis, whereby autistic individuals may also show additional impairments in empathy, best explained by the presence of psychopathy as a distinct and additional disorder. However, research in this area is limited. Therefore, the aim of the current study was to systematically review the literature to: (a) understand the relationship between psychopathy and autism, and (b) to describe the clinical manifestation of the two constructs when they co-occur. Studies examining this relationship are critical in furthering our knowledge of this small but clinically significant population group and may help to inform the types of interventions appropriate for those who meet the criteria for both constructs, and especially those who encounter criminal justice as a consequence of their behaviour. The review will encompass traits of each disorder to reflect the spectrum nature of both constructs. Research on children with CUTs (considered a pre-cursor to adult psychopathy) will be included because early identification can help prevent serious risk through successful early intervention.

2 MethodThis systematic review was conducted according to PRISMA guidelines (26) and was registered with PROSPERO (registration number CRD42023413672).

2.1 Search strategyRelevant studies were identified by systematic searching of the following databases: PsychINFO; CINAHL Ultimate; Medline Ultimate. Google Scholar was also searched and backward searching of identified papers was completed. Grey literature was searched through www.opengrey.eu. Initial searches were undertaken in March 2023 and completed in April 2023. Key terms were searched using English and American terminology, spelling, and truncation to ensure that all variant word endings were identified. Search terms were combined using the term ‘AND’, Table 1.

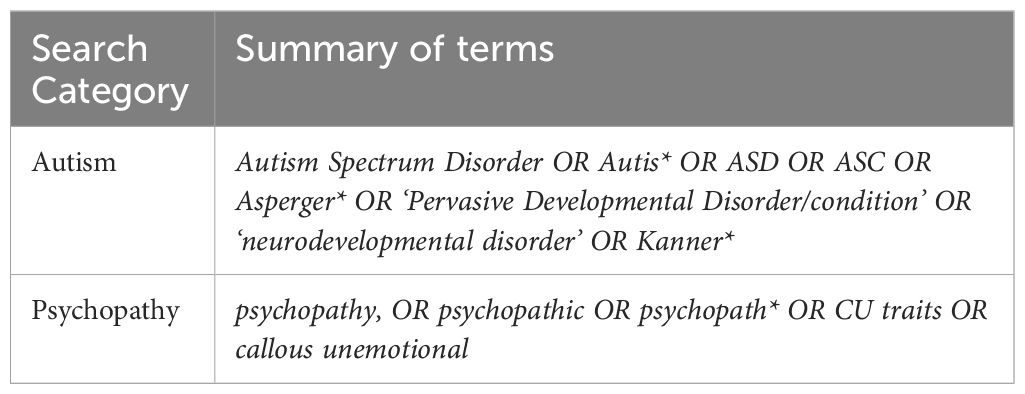

Table 1 Summary of search terms.

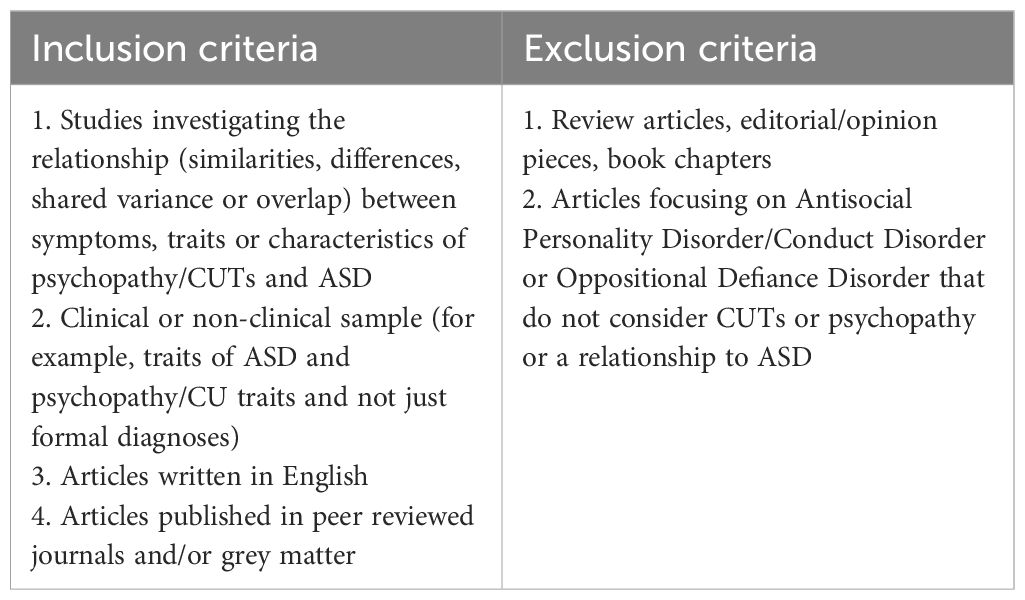

To ensure searches produced relevant results only, the above search terms were restricted to title only and a further specified term of ‘NOT psychopathology’ was included within the title or abstract. This was because initial searches without this clarification produced multiple inapplicable results. Searches were restricted to English language and academic journals or dissertations, in line with the eligibility criteria below, Table 2.

Table 2 Eligibility criteria.

Due to limited research in this area, no limiters or restrictions were placed upon study design or study date.

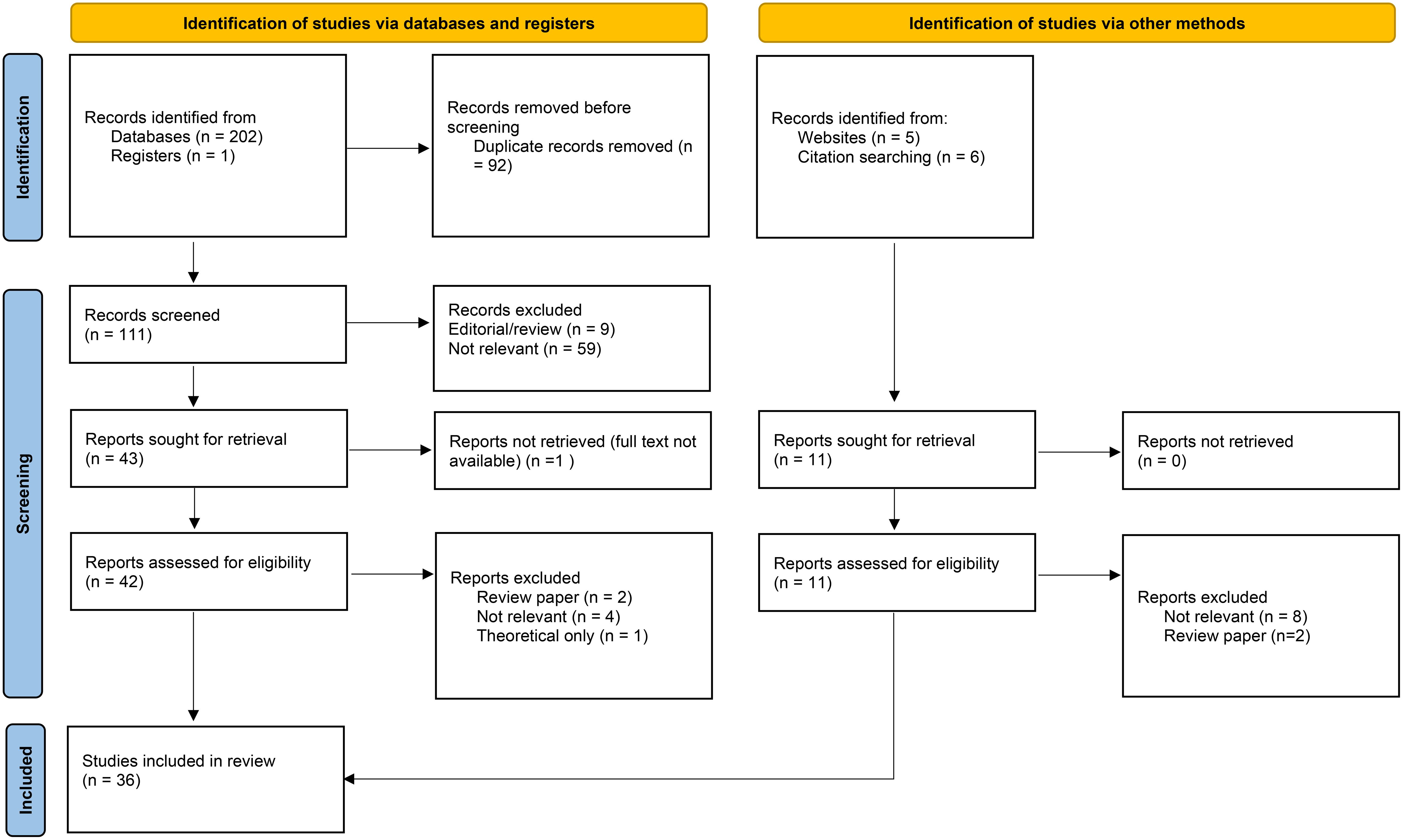

2.2 Screening and article selectionArticle selection was completed by author KM, with 30% of search results also screened by an independent, masked, second rater (HW), with an interrater agreement of 100%. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) (26) guidance was used to refine studies and can be seen in Figure 1 which details article selection. First, duplicates were electronically removed using EBSCO. Abstracts were then screened against the eligibility criteria and results were rejected which did not meet criteria. This included book chapters or papers not specifically looking at both autism and psychopathy in some manner. Full text screening of remaining articles was then completed.

Figure 1 PRISMA diagram showing screening and identification of eligible studies (27).

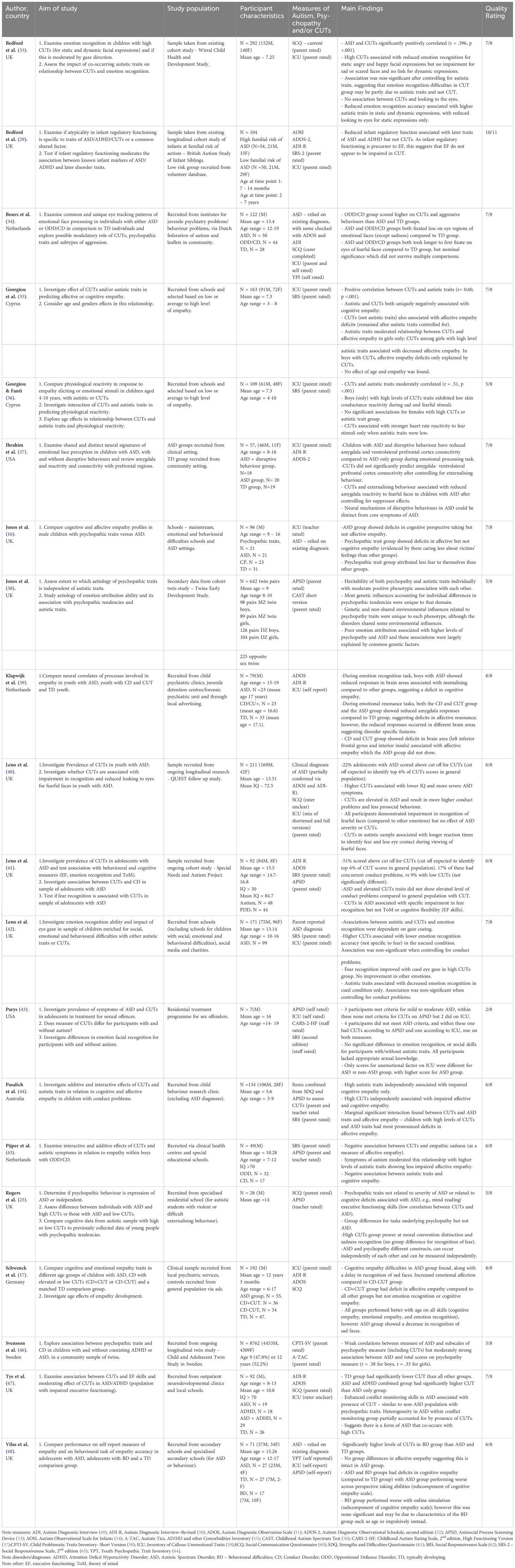

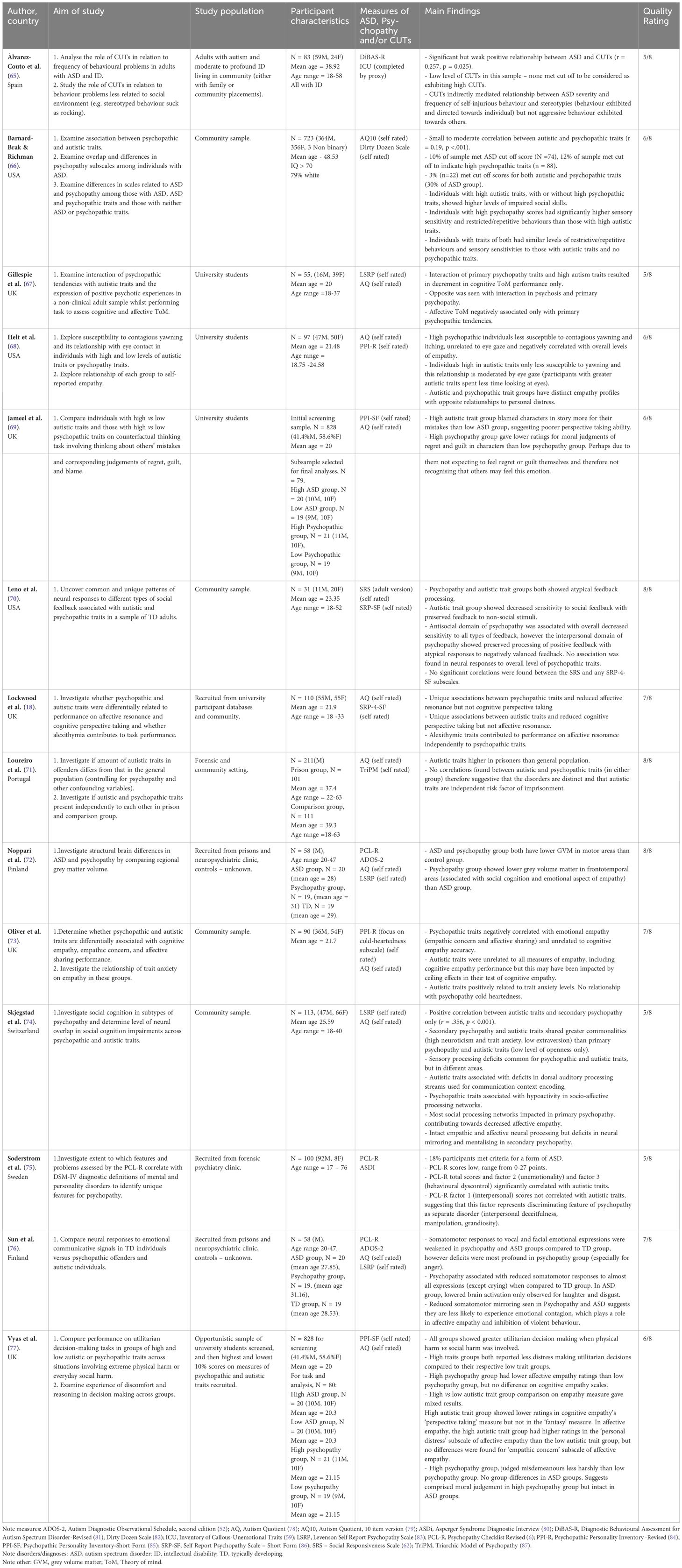

3 Analysis3.1 Data extractionThe following data were extracted from each paper: author and country, study population and participant characteristics, measure of autism/psychopathy/CUTs administered and main findings. These data were considered relevant to either quality appraisal of the studies or relevant for synthesis of findings in relation research question. Thirty percent of papers were checked by HW, with an inter-rater agreement of 88%. All disagreements were resolved through discussion.

3.2 Quality appraisalPrior to evidence synthesis, a critical appraisal of the literature is required to enable a judgement about bias and subsequent effectiveness. Study quality was assessed using the ‘Checklist for Analytical Cross-Sectional Studies’ (28). This tool is used to assess the methodological quality of each included study and assess sources of bias. One included study (29) was a longitudinal cohort study and therefore the ‘Checklist for Cohort Studies’ was used instead (30). These tools are recognised as a reliable tool for use in systematic reviews to evaluate variation in study designs and methodology (31). Again, 30% of papers were checked by HW, with an inter-rater agreement of 82% and disagreements resolved through discussion.

3.3 SynthesisA narrative synthesis approach was adopted due to the broad spectrum of included research. This was conducted in line with guidance by Popay et al. (32), who describe this technique as a synthesis of studies relying on the use of words to summarise and explain findings.

4 Results4.1 Study settings and sample sizeOf the 214 papers identified during initial searches, 92 duplicates were removed, 71 were not relevant and 13 were reviews or editorial pieces. The full text article was unavailable for one paper, and another was theoretical only, leaving 36 studies that met the eligibility criteria and were included, Figure 1. Table 3 shows 22 studies that recruited children and Table 4 shows 14 studies that included adult participants.

Table 3 Studies investigating the relationship between psychopathy/ callous unemotional traits and autism/autistic traits in children.

Table 4 Studies Investigating the Relationship Between Psychopathy/Psychopathic Traits and Autism/Autistic Traits in Adults.

Studies were conducted in 11 Western countries: UK (17), USA (5), Netherlands (3), Sweden (2), Finland (2), Cyprus (2), Spain (1), Switzerland (1), Germany (1), Portugal (1) and Australia (1). Twenty studies recruited from community settings, including schools and universities, and a further five were recruited from existing cohort/longitudinal studies. Five studies recruited from clinical settings such as child behaviour clinics and six recruited from forensic settings. One study focused specifically on sex offenders (43). Sample sizes ranged from seven (43), in an unpublished thesis, to several thousand in large scale twin studies (46, 88).

4.2 Participant characteristicsA total of 12115 children were recruited across the included studies, including 6654 males and 5461 females. Of these, 746 had primary diagnoses of autism, autistic traits, or were identified as being at familial risk of autism, although many also had co-morbid diagnoses or additional behavioural difficulties. Three hundred and nineteen were considered to have oppositional defiant disorder, conduct disorder/problems, CUT or psychopathic traits, whilst 11032 were either identified as typically developing or no information was provided. Eighteen participants only had a diagnosis of ADHD. A total of 1888 adults were recruited across our included studies, including 1133 males, 752 females and 3 people who identified as non-binary. Of these, 163 had diagnoses of autism or had autistic traits, 80 had psychopathic traits and the remaining were either considered typically developing or the information was not provided.

Twenty-four studies included males and females, whereas 12 only recruited males. Participant age ranged from seven months (29) to 63 years (71). One study included participants with intellectual disability (65), and three studies included those with mixed ability levels: Leno et al. (41) reported a mean IQ of 84.7, Leno et al. (40) reported a mean IQ of 72.5, and Soderstrom et al. (75) reported that 17% of participants had an IQ below 70.

4.3 Quality appraisalQuality appraisal ratings are found in Tables 1 and 2. Scores ranged from two to eight, with five fulfilling the full criteria (17, 39, 70–72). An unpublished thesis (43), scored two out of eight. This low score was due to the small sample size (N=7) meaning that the statistical analysis was judged as inappropriate, whilst there was little information on eligibility criteria, confounding variables or appropriateness of the measures used.

4.4 Measurement toolsSome studies involved administering a gold standard diagnostic tool to participants including the Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule (ADOS) (89) and the Autism Diagnostic Interview-Revised (ADI-R) (50), while two studies did not confirm existing diagnoses (16, 48), although both had large sample sizes, making this a time-consuming exercise. Commonly used measures of autistic traits were the Autism Quotient (AQ), the Social Communication Questionnaire (SCQ), and the Social Responsiveness Scale (SRS). These were considered reliable and valid measures, and appropriate screening tools. Research has shown that screening tools are not entirely predictive of diagnosis (90), making it important to differentiate between autistic traits and a formal diagnosis of autism across studies.

There was large variation in the measurement of psychopathy/CUTs. Many studies used the Inventory of Callous Unemotional Traits (ICU) (59), which is a 24-item scale designed to measure CUTs in children. Whilst this is a well-researched and validated measure (see Cardinale and Marsh (10) for a review), no study has validated its use in autistic children. Several studies used this measure (34, 37, 40, 47, 65). Other researchers (16, 25, 41) administered the Antisocial Process Screening Device (APSD) (53), measuring the wider construct of psychopathy in young people, but again, this has not been validated for use with autistic children. Rogers et al. (25), acknowledged this and confirmed that the APSD positively correlated with conduct problems as expected, suggesting convergent validity.

The authors of three studies (72, 75, 76) administered the Psychopathy Check List-Revised (PCL-R) (6), which is considered to be a gold standard tool. All other studies relied on self-report measures of psychopathy, which should be viewed critically as psychopathic individuals tend to lack insight into the nature of their psychopathology (91). Additionally, using self-report measures with those known to be manipulative and deceptive increases the risk of response bias (92). Research about the reliability and validity of self-report measures of psychopathy in autistic people is lacking. There is evidence that self-report personality measures used with autistic children are questionable (93), and three of the included studies used a psychopathy self-report measure with children (39, 43, 48). Vilas et al. (48) acknowledged the limitations of this and administered multiple measures to circumvent this problem. The use of a single measure of psychopathy is advised against (91); however, only five studies administered multiple measures (34, 43, 48, 72, 76).

5 Autism and callous and unemotional traits in children5.1 Estimated prevalenceLeno et al. (40) reported that 22% of autistic children scored above their designated cut off to indicate the presence of CUTs. However, some participants completed the full ICU measure and others a shortened version. Ideally, prevalence studies should include a representative sample and exclude any possible biases; the full ICU should have been administered to all participants, and their autism diagnosis confirmed. Two groups of researchers administered the ASPD, reporting different rates of CUTs. Leno et al. (41) reported that 51% of autistic adolescents fell into their category of high CUTs. In contrast, Rogers et al. (25) reported that their sample had a mean CUT score of 4.77, which is considered an ‘average’ CUT score. However, methodological differences between these studies make comparison challenging.

5.2 Autistic traits and callous and unemotional traitsThree studies (33, 35, 36) with large, mixed gender samples reported a positive correlation between CUTs and autistic traits (r = .40, r = 0.60 and r = .51 respectively) amongst typically developing children. Studies reporting higher correlations recruited participants based upon having either low or high empathy levels which may have inflated the correlation.

5.3 Autism and psychopathyThree studies made use of samples of those with an existing autism diagnosis (25, 40, 46). Svensson et al. (46) undertook a large twin study (N = 8762), and administered the Child Problematic Trait Inventory – Short Version to index psychopathy. They reported a significant relationship between psychopathy and autism amongst boys, r = .38, and girls, r = .33, bearing in mind that there may be validity issues with their choice of measure (94). Leno et al. (40) reported that higher CUTs were associated with more severe autistic traits, lower levels of prosocial behaviour and increased conduct problems. In contrast, Rogers et al. (25) reported no relationship between CUTs or psychopathy and autism and cognitive abilities in a much smaller study of autistic boys.

5.4 EmpathyAs expected, there was evidence that autism/autistic traits and CUTs/psychopathy in children is associated with distinct empathetic profiles. Children with autistic traits demonstrated deficits in cognitive empathy with intact affective empathy (35, 44, 45), and the same relationship was observed in children with diagnoses of autism (16, 17, 39, 48). These results appeared consistent despite the variation in the measurement of empathy and methods across studies. The relationship between CUTs/psychopathy and empathy appeared less clear; some studies reported diminished affective empathy and intact cognitive empathy (16, 17), whilst others reported diminished affective and cognitive empathy (35, 44).

Studies looking at the relationship between CUTs and autistic traits had contradictory results. While Pijper et al. (45) reported a negative association between CUTs and affective empathy in their sample of 10-year-old boys with conduct disorder as expected, the relationship was moderated by autistic traits; those with higher autistic traits and CUTs exhibited less impaired affective empathy. In contrast, Pasalich et al. (44) found that 5-year-old boys and girls with conduct disorder and high levels of both CUTs and autistic traits displayed the most pronounced deficits in affective empathy. These contradictory findings may be explained by: (a) sex differences: there is limited evidence that high CUTs and high autistic traits are associated with decreased affective empathy in girls only (35) and Pijper et al. (45) only included a sample of boys, and (b) difficulties with the measurement of empathy: both Georgiou et al. (35) and Pasalich et al. (44) used the Griffith Empathy Measure (95) and there is evidence that the affective empathy scale lacks construct validity (96). Age may also have impacted on these findings as there is evidence of improved performance with age on both types of empathy in all participants (17), as would be expected, and Pijper et al. (45) included older children relative to Pasalich et al. (44). Nonetheless, it’s worth noting that another study reported no relationship between age and empathy (35).

5.5 Cognitive profileThere was some evidence that psychopathy and autism are distinct constructs and the interaction of these may create a distinct cognitive profile. Bedford et al. (29) reported that reduced infant regulatory function (a precursor to executive functioning) is associated with later autistic traits but not CUTs in their longitudinal study, suggesting the two constructs are associated with differing executive functioning abilities. However, they did not include data for children older than seven years, and thus lacked information about continued development. When exploring the interaction of CUTs and autistic traits, Tye et al. (47) reported that autistic children with high CUTs exhibited enhanced conflict monitoring skills. Whilst this indicates a potentially advantageous role of CUTs on executive functioning in this group of children, the study was a small-scale preliminary study using a specific task to assess conflict monitoring, which may not be generalisable to other executive functioning skills. Two studies found that CUTs/psychopathic traits in autistic children were unrelated to the executive functioning skills associated with autism (25, 41).

5.6 Emotion recognitionNine studies explored emotion recognition. Ibrahim et al. (37) reported that autistic children with CUTs displayed reduced amygdala activity to fearful faces compared to those with autism only. Conversely, Rogers et al. (25) found that all autistic children demonstrated fear recognition, regardless of the presence or absence of psychopathic traits, although this study focused on the wider construct of psychopathy (not CUTs). Results for sadness differed, with Rogers et al. (25) reporting that autistic boys with high psychopathic traits had poorer sadness recognition than those with low psychopathic traits. These studies used morphed faces (25) or still pictures (37) which may not accurately reflect how emotions are viewed during in-person social interactions. Bedford et al. (33) theorised that dynamic expressions are a more accurate representation of social interactions and compared static pictures with short video clips of people performing facial expressions. They reported that CUTs in typically developing children were associated with reduced emotion recognition for static facial expressions depicting anger and happiness. This association was not observed for dynamic facial expressions and disappeared when controlling for autistic traits. In contrast, autistic traits were associated with poorer overall emotion recognition for both static and dynamic expressions. Leno et al. (40) adapted the emotion recognition stimuli from Bedford et al. (33) and investigated emotion recognition in autistic adolescents, reporting that all participants demonstrated impairment in recognition of fearful faces with no relationship with autism severity or CUTs.

Several studies investigated the role of eye gaze on emotion recognition (33, 34, 40, 42). Bours et al. (34) reported that autistic adolescents and adolescents with CUTs both showed reduced fixations of the eye regions compared to typically developing adolescents. When considering the interaction of autism and CUTs, Leno et al. (40) found that CUTs in autistic adolescents was associated with longer times to identify fear and reduced eye contact during viewing of fearful faces. Leno et al. (42) then investigated the effect of cueing attention to the eyes in children with either CUTs or autistic traits, finding that this improved fear recognition in children with CUTs (no improvement in other emotions) but had the opposite effect on overall emotion recognition in their autistic trait group, suggesting different underlying mechanisms. However, the relationship between autistic traits, emotion recognition and gaze cueing was non-significant after controlling for conduct problems, emphasising the importance of considering co-occurring psychiatric traits.

Finally, Georgiou and Fanti (36) investigated the relationship between emotional recognition and physiological reactivity and reported that boys with CUTs exhibited low skin conductance reactivity during sad and fearful stimuli, whilst no associations were found amongst girls with CUTs or children of either gender with autistic traits. CUTs were associated with stronger heart reactivity to fear stimuli amongst children with low levels of autistic traits. They theorised that low skin conductance reflected fearlessness in children with CUTs, whilst stronger heart rate reflected thrill seeking. Unfortunately, the authors did not measure anxiety which may impact physiological responses.

6 Autism and psychopathy in adults6.1 PrevalenceBarnard-Brak and Richman (66) looked at the prevalence of autistic and psychopathic traits amongst a community sample (N = 723) without a diagnosis of autism, finding that 10% met screening cut off to indicate autistic traits and 12% met screening cut off to indicate psychopathic traits; 30% of the autistic trait group also meet criteria for psychopathic traits. The study relied on brief self-report measures of autistic [AQ-10; (79)] and psychopathic traits =[Dirty Dozen Scale; (82)], which are not diagnostic, and findings should be viewed in the context this limitation.

6.2 The relationship between autistic and psychopathic traitsSeveral studies commented on the correlation between psychopathy and autism, with wide variation in the source of participants, measures, and methodology and all administering self-reports of psychopathic and autistic traits. In community samples, Barnard-Brak and Richman (66), reported a weak but significant positive corelation, r = .19, whilst other studies reported no significant correlation (70, 71). No correlation was found between autistic and psychopathic traits in a forensic setting (71).

On the other hand, Soderstrom et al. (75) recruited violent offenders and administered the gold standard, PCL-R, and reported a significant but small positive correlation between PCL-R total, factor two (unemotionality), factor three (behavioural dyscontrol), and autistic traits. No correlation between autistic traits and factor one (interpersonal) was found. Only one study differentiated primary and secondary psychopathy, reporting a positive correlation between autistic traits and secondary psychopathy traits only (74). All the aforementioned studies measured autistic traits, and only one study recruited adults with a diagnosis of autism and intellectual disability, observing a small but significant positive relationship between autism and CUTs (65).

6.3 EmpathyMany studies recruited typically developing individuals without a diagnosis of autism and grouped them according to whether they had high or low autistic or psychopathic traits, drawing comparisons. As expected, findings indicated that psychopathic traits were associated with diminished affective empathy and intact cognitive empathy (18, 73, 77) whilst autistic traits are associated with reduced cognitive empathy but not affective empathy (18, 69). Of note, these studies all recruited participants with a mean age of 20-21 years, an age at which the human brain is still developing, and therefore results may not be applicable to older adults. In one study, Oliver et al. (73) failed to find a relationship between autistic traits and all measures of empathy, but the cognitive empathy test used was subject to ceiling effects, reducing the sensitivity of this task.

Studies of emotional contagion (thought to reflect affective empathy) highlighted impairment in typically developing adults with psychopathic traits and individuals with autistic traits, with greatest impairment observed in those with psychopathic traits (68). Helt et al. (68) observed that individuals with high traits of either autism or psychopathy both showed reduced yawn contagion, but the psychopathic trait group also showed reduced contagion of itching. The relationship between autistic traits and yawn contagion was moderated by eye gaze suggesting that some of the reduced contagion was due to less time spent looking at the eyes. These findings contribute to the evidence that psychopathy is associated with diminished affective empathy to a greater extent than autism. Similar results were found in autistic adults with a diagnosis; Noppari et al. (72) recruited violent offenders with high psychopathic traits, autistic adults and a typically developing comparison group. They observed weakened somatomotor responses in both their violent offender group and their autistic group (compared to their comparison group), however the most pronounced deficits were observed in the violent offender group.

Only one study investigated the interaction of psychopathic and autistic traits in relation to empathy. Gillespie et al. (67) measured primary and secondary psychopathy traits and autistic traits amongst university students and observed diminished cognitive ToM performance in students with both high primary psychopathy traits and autistic traits, concluding that people with co-occurring traits of both constructs have additional empathy impairments. No interaction effect was seen for affective ToM, which was uniquely associated with primary psychopathic tendencies. Unfortunately, this was a small-scale study, relying on self-report measures.

6.4 Cognitive profileAs with children, there was evidence that psychopathy and autism have different cognitive profiles and the authors of two studies compared high and low autistic or psychopathic trait groups on cognitive processes. The first group reported that adults with high autistic traits tend to blame vignette characters for their mistakes more so than those with low autistic traits, while those with high psychopathic traits attributed lower regret and guilt to vignette characters (69). The second group investigated moral judgment, reporting that the high psychopathic trait group judged misdemeanours less harshly than the low psychopathy group, with no differences in those with high or low autistic traits, leading them to conclude that moral judgement was only affected by psychopathy (77). Although offering insight into the cognitive profiles of autism and psychopathy, neither study investigated the interaction of the two constructs, and both relied on self-report measures from university students, limiting generalisability.

Two additional studies employed brain imagining techniques in individuals with autistic or psychopathic traits. Leno et al. (70) investigated neural feedback processing of social and non-social information, reporting atypical neural feedback processing in both trait groups. Autistic traits were associated with decreased sensitivity to social feedback, whilst those with traits of the antisocial domain of psychopathy showed decreased sensitivity to all feedback and those with traits of the interpersonal domain of psychopathy showed attenuated processing of negative feedback only. Skjegstad et al. (74) reported deficits in both trait groups for socio-affective processing, but again these showed different areas of association; autistic traits were associated with deficits in dorsal auditory processing streams (used for communication context encoding), whilst psychopathic traits were associated with hypoactivity in socio-affective processing networks. This study was exploratory and lacked an a priori power calculation, but both studies suggested distinct neural mechanisms across these constructs. Again, these studies did not investigate the interaction of these traits, failing to shed light on the ‘double hit’ hypothesis.

Regarding the interaction of psychopathy and autistic traits, (65) investigated the mediating role of CUTs in different types of challenging behaviours in a sample of autistic adults with intellectual disability. They reported that CUTs mediated the relationship between challenging behaviours directed towards the self, but not aggressive behaviours directed towards others, therefore proposing that CUTs may have a protective role for self-directed challenging behaviours. However, results must be viewed tentatively as this was a small-scale study that looked only at frequency and not severity of behaviour amongst those with both intellectual disability and autism.

7 DiscussionThis review sought to investigate the relationship between psychopathy and autism and what happens when they co-occur. Thirty-six studies were identified as meeting eligibility criteria, largely published within the last 10 years. The variation in methodologies, study focus, measures and samples recruited, made comparisons difficult, allowing only provisional conclusions to be drawn. Further, few studies investigated the co-occurrence of autism and psychopathy and directly investigated the ‘double hit’ hypothesis making it difficult to draw clear conclusions.

Across all ages, an increased prevalence of CUTs/psychopathy in autistic individuals or in those with high autistic traits appeared to exist relative to the general population and regardless of methodology used. Prevalence rates ranged from 22%-56%, whilst prevalence of psychopathy in the general population is estimated at 4.5% (7). It remains unclear whether autistic children are at risk of developing CUTs and later psychopathy, or whether autism and CUTs/psychopathy are similar constructs and overlap. Multiple limitations were associated with the measures used, drawing urgency to the need to develop measurement tools sensitive enough to untangle this relationship.

Generally, authors reported a positive correlation between autistic and psychopathic traits amongst children (33, 35, 36). However, the authors of one study reported no significant correlation between autistic symptoms and CUTs in diagnosed autistic boys (25). In adults, the positive relationship between autistic and psychopathic traits was generally attenuated relative to children (66, 75) or not found (70, 71). This was also observed in adults with autism and intellectual disability (65). The relationship between psychopathy and autism amongst adults and children may differ due to issues with the sensitivity of measurement tools and development; autistic and psychopathic traits will likely change with maturation.

Several papers evidenced that although the constructs are both associated with empathy dysfunction, the underlying mechanisms differ. In adults, psychopathy/psychopathic traits were generally found to be associated with diminished affective empathy and intact cognitive empathy, whilst the inverse relationship was seen in autism/autistic traits which is consistent with both theory and other research (21, 97). A recent meta-analysis confirmed that psychopathy is associated with diminished affective empathy (98). Research about autism and affective empathy is inconsistent but points towards fewer deficits in this area compared to cognitive empathy (99), with some studies reporting intact affective empathy in autistic individuals (100).

In children, autism/autistic traits were also associated with difficulties with cognitive empathy but not affective empathy while the results for those with CUTs/psychopathy were inconsistent. Some studies reported deficits in both types of empathy and others reported difficulties with affective empathy only. This inconsistency may be due to developmental maturation throughout childhood (101) or gender, as children of both genders with psychopathic traits had difficulties with cognitive empathy but there was some evidence that males overcame these difficulties during their pubertal years (102). However, the authors of one study reported no relationship between age and empathy (35), which is unexpected, whilst another reported improved performance with increasing chronological age (17); however, they included a broader age range (six to 17 years) of boys only with intact cognitive empathy, whereas Georgiou et al. (35) included younger boys and girls (three to eight years).

In the current review, the findings from studies about emotion recognition were mixed. In adults and children, CUTs/psychopathy was associated with reduced emotion experience and emotion recognition ability, in particular, recognition of fear and sadness was diminished. These deficits largely remained in the presence of autism, for example, autistic boys with psychopathic traits showed poorer sadness recognition (25), and reduced amygdala activity to fearful faces was observed in autistic children with CUTs (37). However, results were inconsistent across studies with one study reporting a non-significant association between CUTs and emotion recognition after controlling for autism (33).

Previous research has indicated that fear recognition deficits in psychopathy are associated with poor attention to the eyes, resulting in blunted affect and impaired processing of affective cues in others (103). This association has been found across many samples, including children with CUTs (24, 103), community samples (104) and psychopathic offenders (105, 106), with similar findings in the current review identified by Bours et al. (34). Regarding the co-occurrence of CUTs and autism, it appears that deficits in eye gaze remain, with autistic children with CUTs taking longer to identify fear and showing reduced eye contact when viewing fearful faces, relative to autistic children with fewer CUTs (40).

Cueing to the eyes has been shown to improve fear recognition in children with CUTs (103). This was replicated in a single study identified in the current review, but the converse relationship was found in an autistic trait group who evidenced reduced fear recognition following cueing (42). It is possible that autistic individuals view eyes as threatening or over-arousing stimuli, thus avoiding this area and missing social processing cues which then interferes with emotion processing (107). This may explain why cueing to the eyes reduced fear recognition ability in autistic individuals but not in individuals with CUTs.

With regards to the ‘double hit’, Rogers et al. (25) reported that although psychopathy and autism can co-occur, they are not part of the same construct, finding that autistic boys with CUTs have additional impairments in moral convention distinction and sadness recognition. In the current review, two studies reported increased empathy deficits in individuals with traits of both; Pasalich et al. (44) found that boys with elevated CUTs and autistic traits showed greater impairment in affective empathy and in adults, and Gillespie et al. (67) found that the interaction of autistic and psychopathic traits was associated with reduced cognitive ToM but not affective ToM. They defined cognitive ToM as the ability to infer thoughts, intentions and beliefs of another and affective ToM as the ability to understand another’s emotions. These studies offer support to the ‘double hit’ hypothesis, suggesting increased deficits when the constructs co-exist. However, contrasting results were reported by other studies which indicated that the co-occurrence of these constructs offers enhanced skills, including less impaired affective empathy (45) and greater conflict monitoring skills (47). Unfortunately, based upon the studies included with the current systematic review, it was difficult to coherently describe the clinical manifestation of co-occurring autism and psychopathy due to some mixed findings. However, our findings offer support to the suggestion that autism and psychopathy are distinct constructs which further alter the empathic ability and cognitive ability of an individual when they co-exist.

7.1 Strengths and limitationsIn the current review, the search strategy restricted the search terms to the title only and included the specifier ‘NOT psychopathology’. Although this was done in efforts to screen out inapplicable results, it could have potentially led to the exclusion of some studies. The inclusion of the grey literature was a strength, but only one unpublished thesis was found. It is also important to recognise the wide focus of the review as both a strength and a limitation. Whilst this allowed for inclusion of a broad range of research, the wide focus also made it challenging to draw more specific conclusions, which may have been possible by restricting the eligibility criteria. Psychopathy and autism are highly heterogeneous, and the studies recruited a broad range of participants which is perhaps reflected in the variation of results.

In terms of limitations of the included research, only two studies (67, 74) differentiated between primary and secondary psychopathy and none considered the impact of adverse childhood experiences. In psychopathy research, children with CUTs showed strongest deficits in emotion recognition when there was no history of maltreatment, suggesting that this may be a feature of the primary variant only (108). As adverse childhood experiences are common in autistic children (109), this is an important variable to consider when seeking to determine the relationship between psychopathy and autism.

7.2 Clinical implicationsThe increased prevalence of CUTs/psychopathy in autistic individuals underscores the importance of assessing psychopathy as part of the evaluation of autistic offenders or those at risk of offending to better understand their presentation. Understanding this at an early stage could lead to more targeted treatment options. The studies included within this review were characterised by multiple difficulties with measurement, including lack of validated measures for identifying psychopathic traits within autistic individuals, highlighting this as an area requiring attention. There was a lack of intervention studies, however there was some evidence to suggest that interventions to improve eye contact may be a helpful strategy to improve emotion recognition in psychopathic individuals but may have a detrimental impact for autistic individuals (42). The impact of such interventions for individuals with both psychopathy and autism is unclear but clinicians should be aware of the different underlying mechanisms and consider this with implementation of any emotion recognition strategies used.

7.3 Future directionsAlthough research in this area appear to have grown substantially since Rogers et al. (25) introduced the concept of the ‘double hit’ hypothesis, clear gaps remain. Firstly, there remains a lack of research focusing on the interaction of both autism and psychopathy which is critical in furthering our understanding of the clinical manifestation of the two constructs when they co-occur. Age and gender remain relatively unexplored variables, with fewer studies focusing on females which may be important given indicated sex differences in psychopathy (110). The presentation of primary and secondary psychopathy variants in autistic individuals is unexplored and may be important as autistic individuals experience increased adverse childhood events. Furthermore, future research would benefit from longitudinal studies exploring the developmental trajectory of autistic adults with co-morbid psychopathy or autistic children with CUT. Finally, to aid research in this area, it is essential to establish the validity of measures of psychopathy within autistic individuals, as well as the validity of measures of autism with those scoring high on measures of psychopathy. It was notable that there was a lack of studies about autistic traits amongst those with high psychopathy. These directions will all support better understanding of the relationship between psychopathy and autism and support the development of appropriate care pathways within clinical and forensic systems.

Data availability statementThe original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributionsKM: Methodology, Formal analysis, Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft. HW: Formal analysis, Writing – review & editing. FB: Supervision, Writing – review & editing. PL: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Supervision, Methodology, Formal analysis, Conceptualization.

FundingThe author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s noteAll claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References2. Zeidan J, Fombonne E, Scorah J, Ibrahim A, Durkin MS, Saxena S, et al. Global prevalence of autism: A systematic review update. Autism Res. (2022) 15:778–90. doi: 10.1002/aur.2696

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

3. Hill AP, Zuckerman KE, Hagen AD, Kriz DJ, Duvall SW, Van Santen J, et al. Aggressive behavior problems in children with autism spectrum disorders: Prevalence and correlates in a large clinical sample. Res Autism Spectr Disord. (2014) 8:1121–33. doi: 10.1016/J.RASD.2014.05.006

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

4. Mazurek MO, Kanne SM, Wodka EL. Physical aggression in children and adolescents with autism spectrum disorders. Res Autism Spectr Disord. (2013) 7:455–65. doi: 10.1016/j.rasd.2012.11.004

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

5. Cleckley H. The mask of sanity; an attempt to reinterpret the so-called psychopathic personality. Mosby. (1941).

6. Hare R. The hare psychopathy checklist - revised. Toronto: Multi-Health Systems (1991).

7. Sanz-García A, Gesteira C, Sanz J, Mp G-V. Prevalence of psychopathy in the general adult population: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Psychol. (2021) 12:661044. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.661044

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

9. Yildirim BO, Derksen JJL. Clarifying the heterogeneity in psychopathic samples: Towards a new continuum of primary and secondary psychopathy. Aggression Violent Behav. (2015) 24:9–41. doi: 10.1016/j.avb.2015.05.001

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

10. Cardinale EM, Marsh AA. The reliability and validity of the Inventory of Callous Unemotional Traits: A meta-analytic review. Assessment. (2020) 27:57–71. doi: 10.1177/1073191117747392

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

11. Tharshini NK, Ibrahim F, Kamaluddin MR, Rathakrishnan B, Che Mohd Nasir N. The link between individual personality traits and criminality: A systematic review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2021) 18:8663. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18168663

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

12. Collins J, Horton K, Gale-St Ives E, Murphy G, Barnoux M. A systematic review of auti

留言 (0)