Dear Editor,

Langerhans cell histiocytosis (LCH) is a rare disease characterised by clonal proliferation of CD1a+ Langerhans cells that infiltrate into various organs, causing tissue damage. Though most commonly present in children less than four years of age, LCH is seen in all age groups. It is more often multisystemic (MS-LCH) in adults (28–69%), most commonly involving the bone (50–66%) followed by the lungs (61.7%) and skin (15–50.5%).1,2 The cutaneous presentation of LCH is highly variable and includes erythematous scaly papules with or without petechiae, papulovesicles, plaques, nodules, erosions and ulcerations most commonly distributed on seborrheic and flexural areas. We present a rare manifestation of LCH in the form of perianal and perineal ulceration with concomitant anal and colonic ulceration.

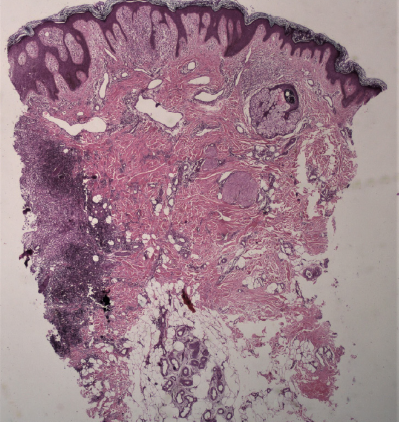

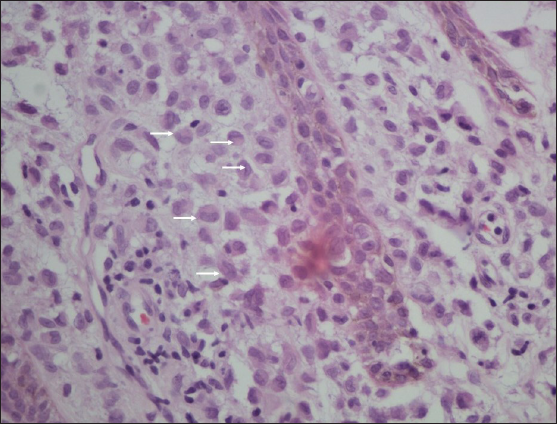

A 21-year-old man was referred to the dermatology outpatient department in view of severely tender symmetric perianal ulcers for seven months. The patient had presented to the gastroenterology department three months ago and undergone a palliative diversion loop sigmoid colostomy in view of recalcitrant faecal leakage per anally as well as tenesmus and significant mucoid discharge for the past three years. He had no other areas of skin involvement, systemic symptoms, weight loss, or bone pain. A pituitary adenoma was detected on magnetic resonance imaging three years ago during evaluation of symptoms of excessive urination and thirst, which had completely resolved post-resection. Examination revealed symmetric, well-defined, severely tender, indurated and ulcerated plaques with a peripheral raised, hyperpigmented border over the natal cleft and perineal area, extending to the medial aspect of the gluteal region and inguinal folds [Figure 1]. It was associated with a foul-smelling, sticky, yellowish discharge. There was no locoregional lymphadenopathy. Routine evaluation, including complete blood count, liver and renal function tests, were within normal limits. Evaluation for his gastrointestinal complaints revealed a long segment thickening involving the rectum and recto-sigmoid junction on the contrast enhanced computed tomography (CECT) abdomen that was metabolically active on positron emission tomography (PET-CT). These findings were suggestive of an inflammatory disease, with possibility of Crohn’s disease or infective colitis. A colonoscopy revealed multiple rectal ulcers and sinuses. Histopathology from the colonic ulcer showed villous adenomatous polypoid tissue with focal low-grade dysplasia and squamous epithelium with subepithelial, dense, acute on chronic inflammation. There were multiple eosinophilic abscesses as well as numerous cells with nuclear grooving. In immunohistochemistry (IHC), these cells were CD1a+, langerin+ and S-100+, suggestive of LCH. On the basis of the above clinical features and evaluation, differential diagnoses of ulcerated perianal LCH, metastatic Crohn’s disease, pyoderma gangrenosum and pyoderma vegetans were considered. Histopathological examination of a biopsy taken from the ulcer edge revealed a large collection of Langerhans cells in the papillary dermis [Figure 2], admixed with lymphocytes, histiocytes and plasma cells, along with mild pigment incontinence. IHC was positive for CD1a & langerin, confirming perianal cutaneous LCH. Serum and urine osmolality, and bone marrow aspiration were normal. CT abdomen had not revealed any hepatosplenomegaly. Patient was referred to medical oncology, and was initiated on a regimen of vinblastine 14 mg (6 mg/m2) IV weekly and prednisolone 95 mg (40 mg/m2) daily. However, he developed severe diabetic ketoacidosis within three weeks and expired despite supportive care.

Export to PPT

Export to PPT

Export to PPT

This patient was a case of adult MS-LCH involving the skin, gastrointestinal tract and likely pituitary gland with atypical cutaneous manifestations in the form of perianal and perineal ulceration. Perianal and anal involvement in LCH is rare. A recent literature review by Hamdan et al. identified 15 published reports of adult perianal LCH.3 The mean age was 38 years, with a male predominance of 73% (11/15). Most of these patients presented with ulcerated to vegetative, indurated plaques with raised borders, similar to our case. The latent period for diagnosis ranged from four months to five years. Eighty percent of these patients had multisystem involvement, with gastrointestinal tract involvement in 13.3% (2 of the 15 cases) which is otherwise rarely seen (0.9%).4 There was a preceding history of diabetes insipidus in one-third of the patients, a known harbinger of LCH.5 Perianal LCH in paediatric age group has also been reported in 8 cases between 1984 and 2016, 75% (6/8) of whom had bony lesions and one case also had gastrointestinal tract involvement.6 Perianal LCH may mimic Crohn’s disease with respect to both perianal and colonic ulcers that show chronic inflammation with crypt distortion and lympho-histiocytic infiltrate.7 A long list of differentials gets elicited in such cases, and so a high index of suspicion is required to exclude the possibilities of conditions like Crohn’s disease, cutaneous tuberculosis, extramammary Paget’s disease, and atypical herpes. LCH should be considered in the list of differentials for perianal ulcerative lesions.

留言 (0)