This article first appeared in the special feature Understanding the Impact of Climate Change.

15 questions for climate change researcher Dr. García Molinos (with subtitles).

Associate Professor Jorge García Molinos

Arctic Research Center, Hokkaido University

(Photo by Manami Kawamoto)

Climate change and global warming are driving intense changes both in marine and terrestrial environments, with knock-on effects for their diverse ecosystems. As habitats change, the diversity and abundance of organisms living in them also change, altering the way ecosystems function and the services they provide to us. Associate Professor Jorge García Molinos spoke about his research into changing ecosystems and their effects on humans dependent on those ecosystems.

Investigating the interplay between climate change and ecosystem change

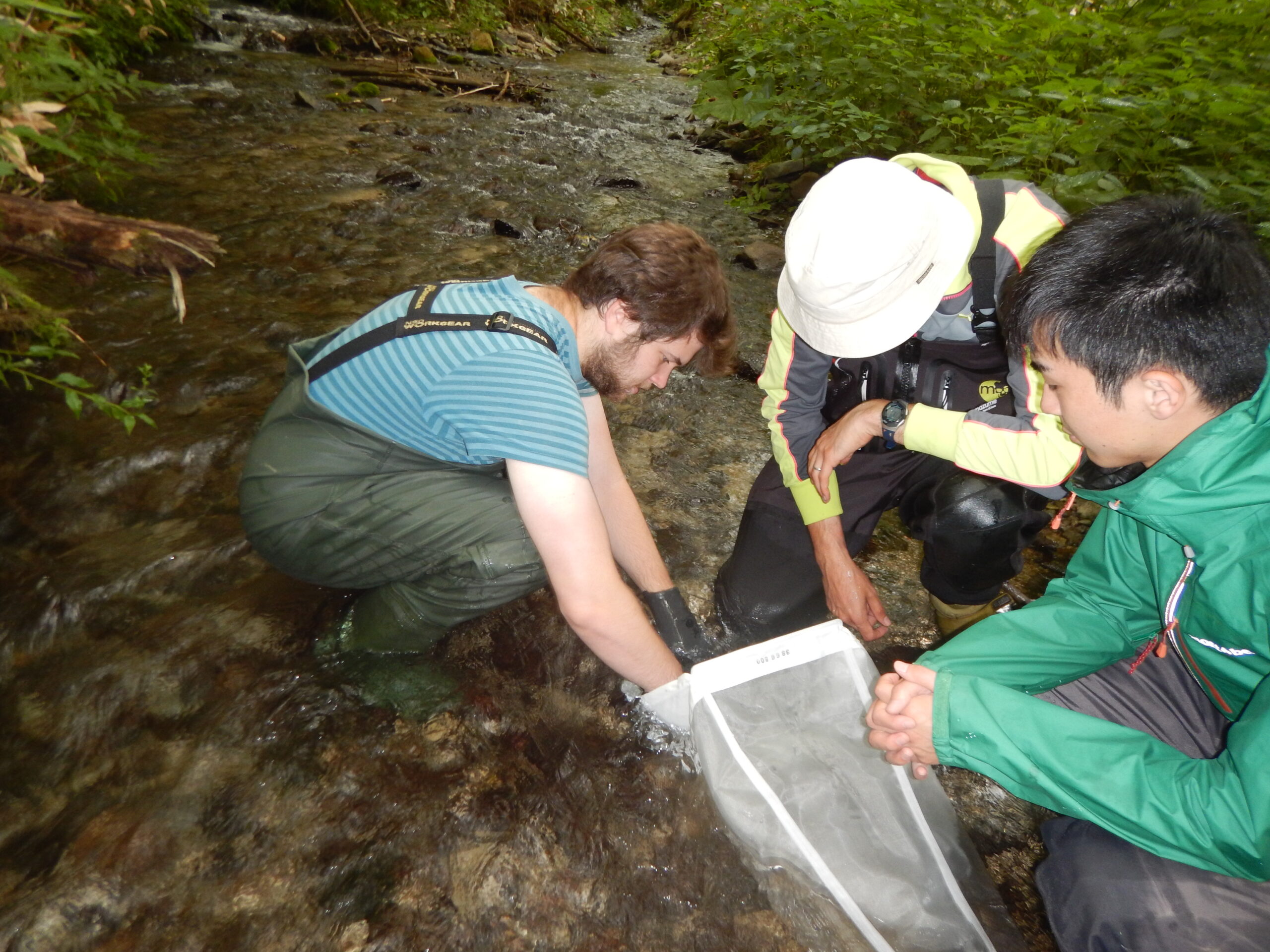

Conducting field work during the summer in a stream of the Sorachi River basin (Kamikawa, Hokkaido) (Photo by Nobuo Ishiyama)

I am an ecologist broadly interested in the effects of climate change on biodiversity. I mostly conduct my research in aquatic environments, from rivers to oceans, although I also work in terrestrial environments. By modifying habitat conditions, climate change is driving a gradual remix of biodiversity in many of these ecosystems as different species respond by shifting their distribution range to track their preferred environmental conditions. Much of my research focus on understanding the ecological implications of these biodiversity changes. More recently, I am also becoming increasingly interested on the implications of these changes for humans who are dependent on these ecosystems.

A multifaceted approach

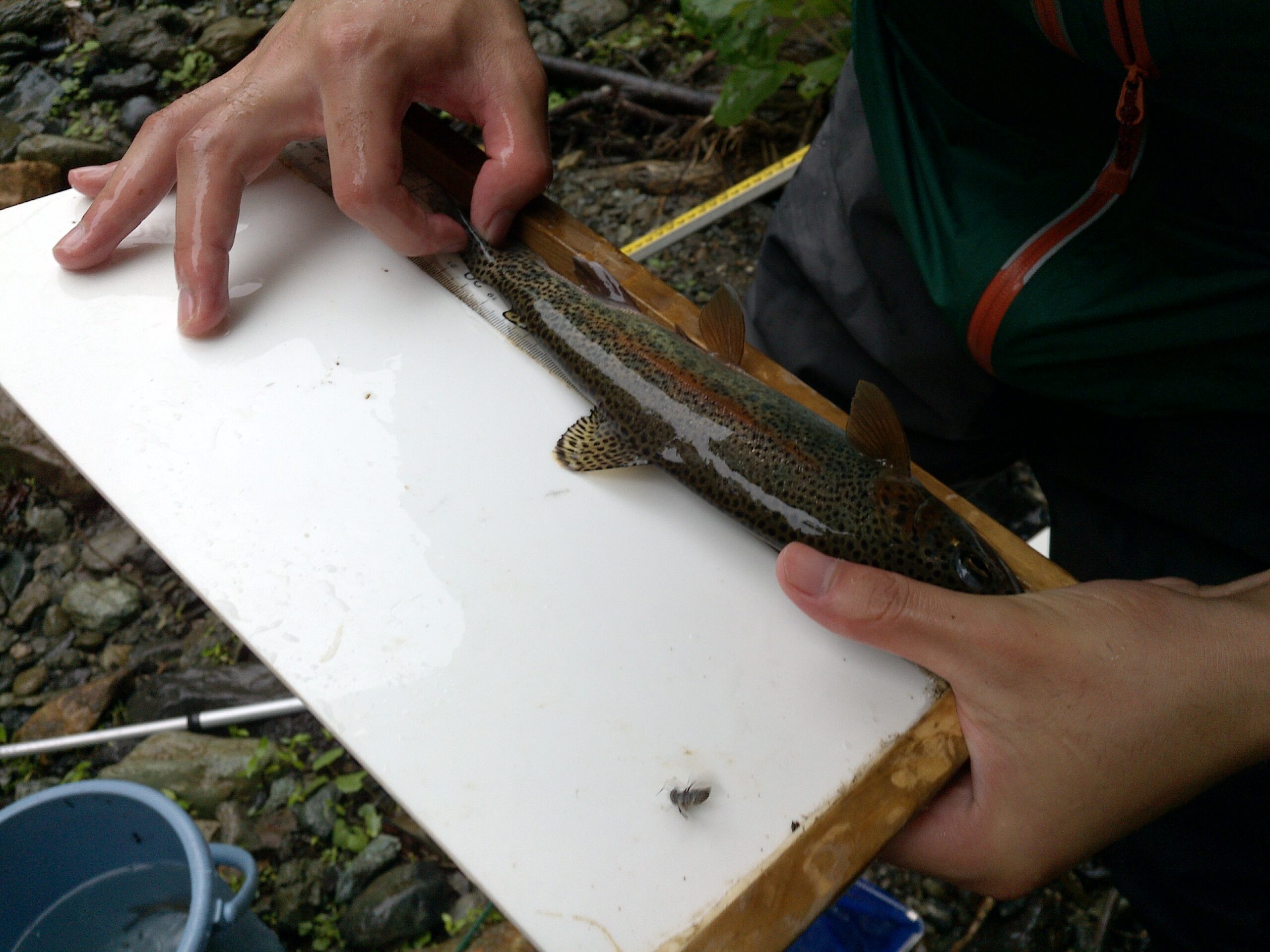

Measuring the fork length of a rainbow trout (Kamikawa, Hokkaido) (Photo by Jorge García Molinos)

Ecosystems are innately very complex. Thus, they require a multi-pronged approach to study and understand them. I use a wide variety of methods in my research: field observations, laboratory experiments and computer modelling. Combining these different but complementary methods allow me to gain a more comprehensive view of the ecosystems we study.

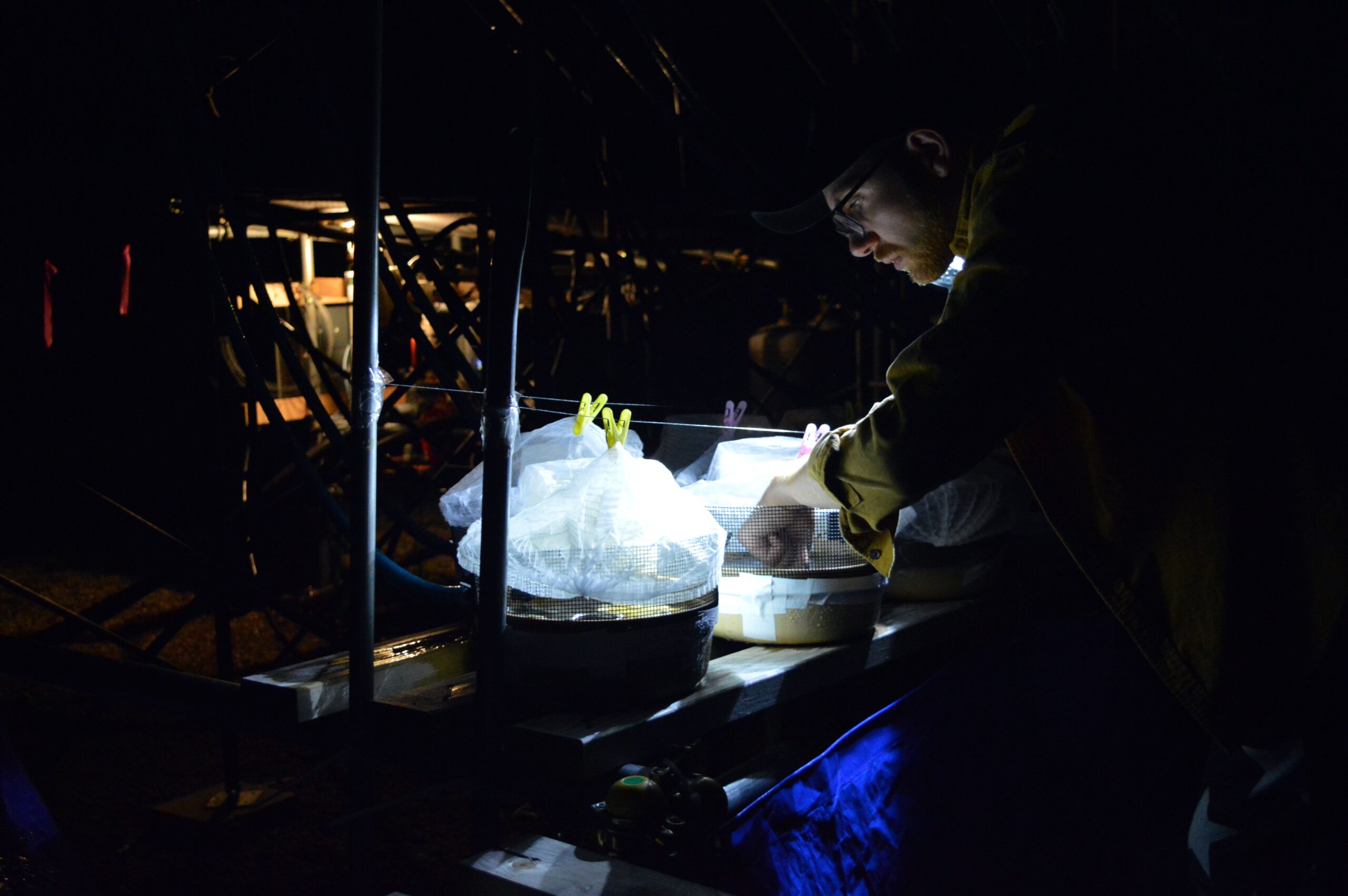

Sorting aquatic benthic invertebrates from samples in the lab for identification (Photo by Samuel Ross)

Concrete evidence of the impact of climate change on ecosystems

Sam Ross conducting an experiment at the Tomakomai Experimental Forest for his PhD research, as part of his research stay as a National Geographic Early Career grantee during the summer of 2019 (Photo by Samuel Ross)

My past and ongoing projects and multiple research collaborations with international teams have provided clear evidence of the effects of climate change on biodiversity redistribution. We are just one of many groups who have revealed concrete examples of these impact of climate change on biodiversity. This growing body of evidence is making awareness of the consequences of climate change to be the highest it has ever been – but social instability and economic problems are more immediate concerns, and climate change takes a backseat to these issues, despite being inextricably linked with them. This is one of the main reasons why I think multidisciplinary approaches to climate change research integrating ecology with human-based disciplines, like economics or health sciences, are urgently needed.

Biodiversity changes in the rivers of Japan

Collecting benthic invertebrates in a small headwater stream in Hokkaido (Photo by Nobuo Ishiyama)

A major project that I lead is a large-scale study of the relationships between thermal habitats and biodiversity in four river catchments across Japan—the Sorachi River and Teshio River in Hokkaido, the Kiso River in Honshu, and the Hiji River in Shikoku. We have continually tracked hourly air and water temperatures at over 200 sites in these rivers, and correlate that with results of biodiversity surveys of fish, invertebrates and algae in the river basins. This data is used to determine the importance of thermal habitats for the species living in those rivers and project the implications of climate warming. We have observed that some fish species, for example, tend to move further upstream to cooler waters as the rivers warm. The project aims to provide important information for improving management and conservation of Japanese rivers under present and future climate change.

Experiences in the field and of Nature

Outdoor experimental set up at the Tomakomai Experimental Forest (Photo by Samuel Ross)

In my case, the most attractive part about my research is the field work—to go out into nature to carry out observations and collect samples. Unfortunately, my responsibilities limit how often I can carry out fieldwork, so I cherish every opportunity.

Herbivorous fish feeding on macroalgae in the coastal waters of Ehime,Japan (Photo by Naoki Kumagai)

I perceive Nature, itself, as something very dynamic or alive, and also something that is very giving. Because I work with environments exposed to human impacts, it’s always surprising how resilient life and nature are. Despite all the impacts and misuse that we often make of nature, nature is always reborn.

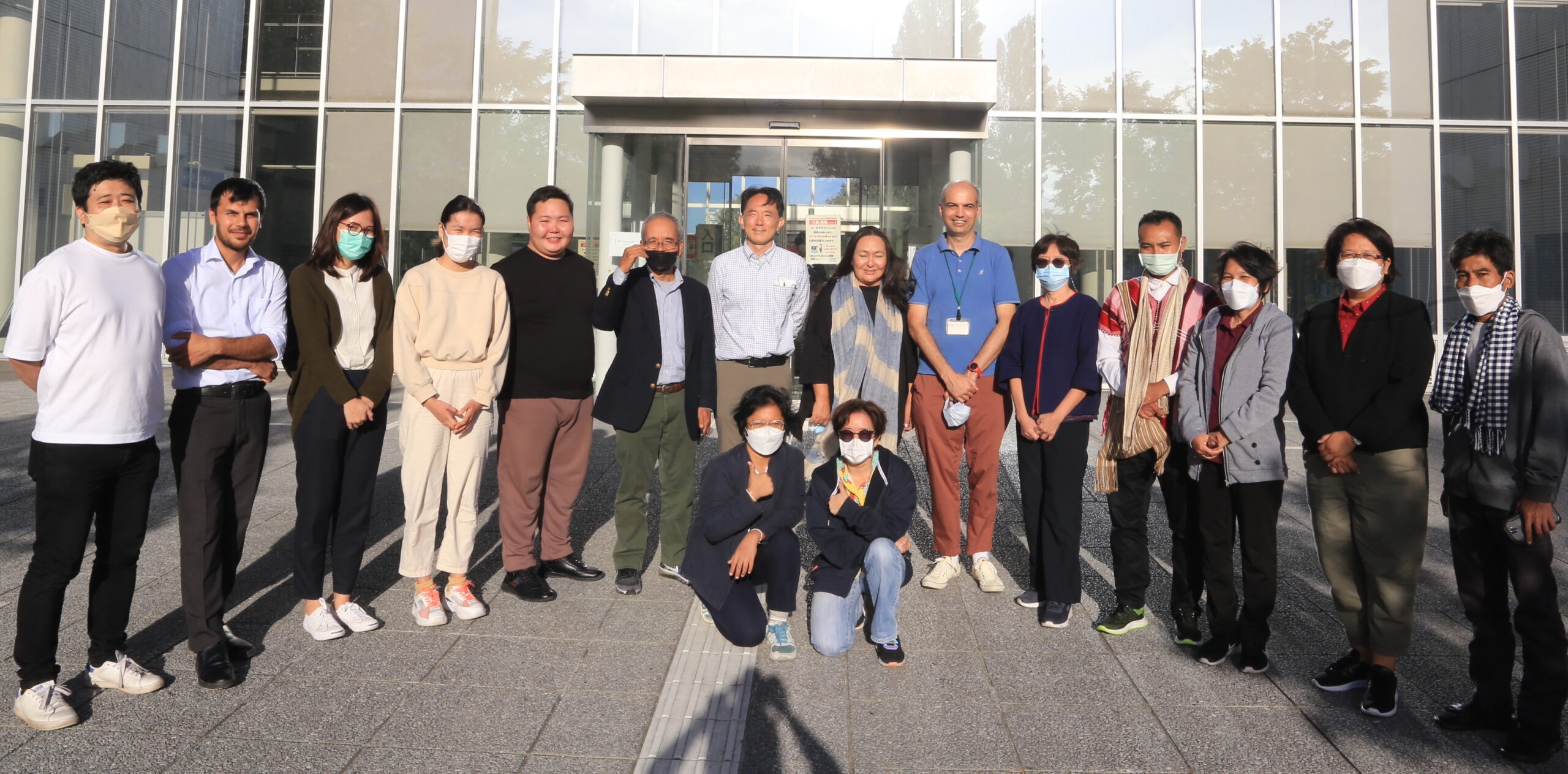

Traditional Food Systems are changing due to climate changeThe largest project that I am currently involved in as a principal investigator is the Climate Change Resilience of Indigenous Socioecological Systems (RISE) project. This is a joint international project comprising several research teams from Japanese (Hokkaido University, the University of Tokyo, and Hiroshima University) as well as international institutions (Mahidol University in Thailand; the North-Eastern Federal University and the Institute for Biological Problems of Cryolithozone in Russia) in this project. We have partnered with several Indigenous communities from the Sakha Republic, Russia, and from Thailand to perform a comparative study of the future implications of climate change on their traditional food systems. We aim to predict how the composition and distribution of species that sustain these traditional food systems will change in the future under different carbon emission scenarios and analyse the potential socioeconomic and nutritional implications of those changes to their livelihoods. The main goal is to provide useful information that can help these communities to understand future vulnerabilities of their food systems and potential adaptation options to respond to those changes.

Local Karen indigenous collaborators discussing with our researchers and collecting field data on traditional food species for the RISE project at Koh Sadeng village in the Thung Yai Naresuan Wildlife Sanctuary, Thailand (Photo by Jorge García Molinos)

Group photo with our colleagues from Mahidol University and Koh Sadeng, one of the two Karen communities we are working with in the RISE project, during a recent field trip (Photo by Sasasoung Jaraskulchai)

This project is especially interesting as we are working with communities from two extremely different regions, one subtropical and the other subarctic, both facing increasing threats from climate change, particularly in terms of the future sustainability of their traditional ways of living.

My philosophy and approach to my research

Japanese, Thai and Russian researchers participating at the 2022 annual meeting for the RISE project hosted at the Arctic Research Center, Hokkaido University (Photo by Ikue Oda)

The most important thing is to enjoy what you are doing, because there is no point in doing research on something that does not motivate or interest you. Another important thing is to be consistent and always remain positive. If your work is not giving you good results, maybe it’s because you are asking the wrong questions! Sometimes failure and wrong results also lead to new questions that are even more interesting than the initial ones. So be flexible and learn from your failures is also very important.

The positivity I mentioned is vital to me when my research do not seem to work. Things often go wrong when you work in the field. I approach these situations as temporary obstacles that I will be able to surmount. Doing research that I enjoy is also a great benefit in this regard.

If, through my research, I can make even a modest contribution to solving the climate change biodiversity crisis and make for a more sustainable future for our society, that would be a great achievement.

Passion is vital for research

Measuring benthic algae concentrations from river stones (Photo by Nobuo Ishiyama)

To those considering a career in research, I would like to emphasize that it is essential that you find something that interests you and encourages you to do research, to solve the global issues that face humanity. I believe that the young are very motivated and extremely capable, but we should not place the burden of expectations upon them; rather, they have every right to expect that we do our best for them.

From forests to freshwater ecology and beyondAs a bachelor student — I majored in Forestry — I was not really considering a career in research until an inspiring professor at the university encouraged me to take up a research assistantship studying aquatic ecology. That was my first contact with research, and it proved to be a watershed moment for me in terms of my professional career. Following my bachelor, I worked at the Environmental Agency in Spain, until I was offered a doctoral position at Trinity College Dublin. However, when I graduated and went back to Spain in 2010, the job market in research and academia was practically non-existent in my country as a result of the Great Recession of 2008–2009. I eventually took up a series of postdocs abroad, first in Ireland and the UK, and finally in Japan, where I worked on freshwater and marine ecology. While working as a postdoc at the National Institute for Environmental Studies in Tsukuba, Hokkaido University launched a tenure track program for foreign faculty. I was accepted into that program — and here I am now!

Photo by Manami Kawamoto

Written by Sohail Keegan Pinto

Part of the special feature Understanding the Impact of Climate Change

留言 (0)