This article first appeared in the special feature Understanding the Impact of Climate Change.

15 questions for climate change researcher Dr. Podolskiy (with subtitles).

Associate Professor Evgeny Podolskiy

Arctic Research Center, Hokkaido University

(Photo by Aprilia Agatha Gunawan).

Greenland is the world’s largest island, situated between the Arctic and Atlantic oceans, with two-thirds of the island north of the Arctic Circle. By area, the Greenland Ice Sheet is second only to Antarctica and has been subject to rapid melting due to global warming. Associate Professor Evgeny Podolskiy talked about his research into ice and whales in Greenland.

Melting of the Greenland Ice Sheet has local and global effects

Water-filled crevasse at Bowdoin Glacier, Greenland (Photo by Evgeny Podolskiy, 2019).

Global warming is currently causing the melting of glaciers and ice sheets all over the world, both in the polar regions and in mountains. The Arctic is the most rapidly warming region on Earth and, consequently, faces the highest rate of ice melting. Greenland is the only landmass covered by a permanent ice sheet outside Antarctica. The ice sheet covers about three-quarters of the island. Despite this, and unlike Antarctica, it is inhabited. Therefore, the loss of Greenland’s ice will not only cause a global rise in the sea level, but will also irrevocably change the lifestyle of the local population. I recall a conversation with a student from Bangladesh, a country far from ice and snow. It struck me that despite this, Bangladesh would be one of the first countries affected by the loss of ice sheets and glaciers. Hence, understanding the dynamics of ice under global warming is crucial.

A nonorthodox view of glaciers

A retreating glacier no longer reaching the sea, Northwest Greenland (Photo by Evgeny Podolskiy, 2019).

Historically, the study of glaciers has been focused on large time scales and slow changes allowing us to treat glaciers as fluid. However, the latter assumption is somewhat wrong to a seismologist because ice responds as a solid under shaking. During the last two decades, it has been realized that glaciers generate a lot of icequakes, and that the corresponding mechanisms – fracturing, calving, sliding, etc. – play an essential role in glacier dynamics. In this area, I have applied the methods and instruments used in seismology to gain a more complete and comprehensive understanding of otherwise inaccessible glacial processes via indirect measurements. This discipline, cryoseismology, is an emerging field, making a part of environmental seismology, now my main area of research.

Seismometers can hear the motion of glaciers

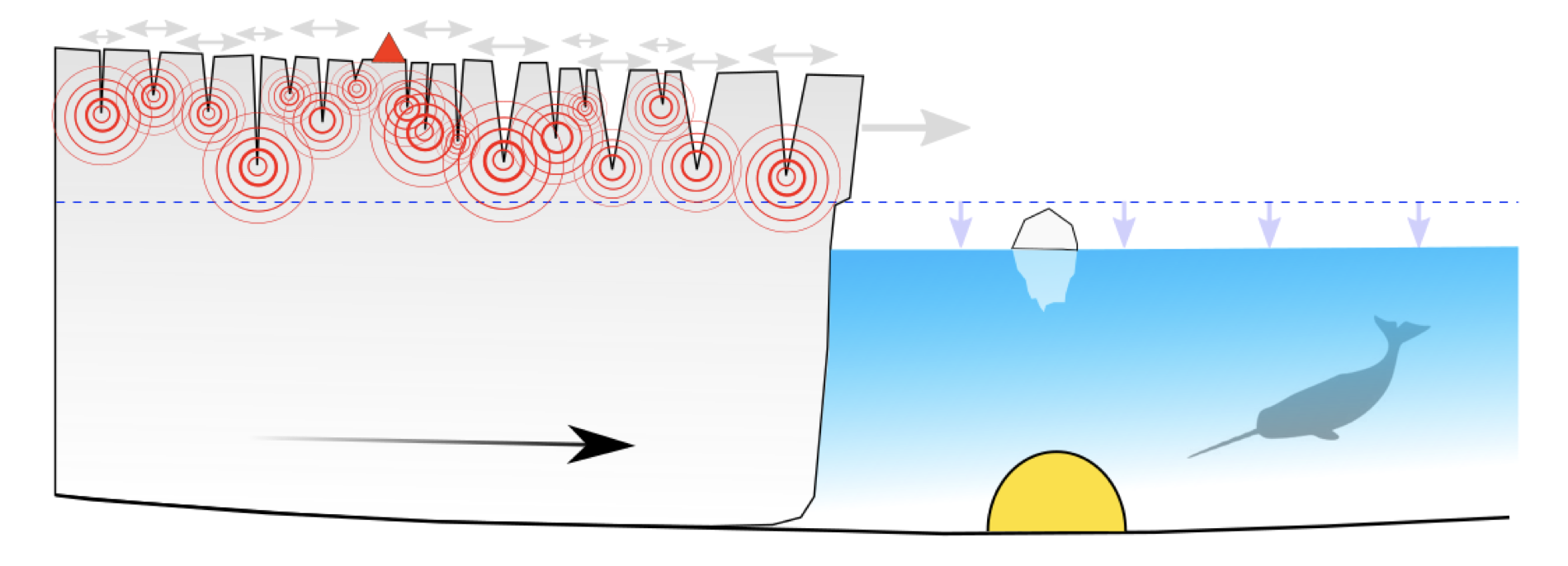

Ocean-bottom seismometer (OBS) near the calving front. The OBS (yellow semicircle) is deployed some distance away from the glacier. It captures all the sounds in the ocean, including vibrations of the seafloor due to glacier movement and whale songs (after Podolskiy et al., Nature Communications, 2021).

After several field seasons in Greenland, I started to suspect that glaciers might radiate seismic energy continuously due to sliding – like tectonic zones do via so-called slow-earthquakes, which may last days and weeks. However, I was not sure how to confirm this, as there were too many overlapping processes and hundreds of icequakes per hour, until it occurred to me that seafloor seismology could provide the answer. My colleagues and I have applied a novel means to study glacier basal motion using an ocean-bottom seismometer (OBS). The OBS was deployed close to the terminus of the glacier (where the glacier meets the sea). It recorded the vibrations of the seafloor over the duration of the deployment, and to our astonishment, the continuous seismic noise was in remarkable correlation to the speed at which the glacier moved during that period. This method might be valuable for monitoring glaciers and lead to more accurate models.

Associate Professor Podolskiy explaining how glaciers cause seismic vibrations that ocean-bottom seismometers detect (Photo by Aprilia Agatha Gunawan).

From Ice to Narwhals

A pod of narwhals, Greenland (Photo by Carsten Egevang, 2019).

Narwhals, the unicorns of the sea, are endemic Arctic whale species. They live in the Arctic Ocean, in areas affluent with ice. Their behaviour and life cycle are not fully understood as the regions in which they live are challenging to access. However, I have encountered pods of narwhals almost every time I went to Greenland for observations — and it recently struck me that I have an unparalleled opportunity to study their behaviour. For instance, seafloor seismological instruments record sound — including the vocalizations of whales. With the advice and assistance of the indigenous Inuit hunters, I could remotely record narwhal vocalizations next to a calving front of a glacier. Yet, close observations are crucial if we want to know what animals are doing. Most recently, in collaboration with the Greenland Institute of Natural Resources (GINR), I studied the behaviour of a satellite-tagged narwhal over three months, and used analytical techniques from my work on turbulence to unveil the patterns in its activity both within a day and across seasons. This is a novel way of studying behaviour of marine animals, and I hope it will inspire other biologists to adopt it.

Attaching a satellite-linked transmitter (biotag) to a live-captured narwhal, Greenland (Photo by Greenland Institute of Natural Resources).

The grandeur of Nature is vast and inspiringI work in the vast wilderness of cold regions—like Greenland and the Pacific Ocean—and in that environment the insignificance and the fragility of humans are brought to the fore. I highly enjoy working in the field because I see the most incredible places on the earth—natural temples the likes of which no human civilization created: giant icebergs and glaciers, mountains and seas. Nevertheless, the impact of anthropogenic global warming is remarkably evident in Greenland, and it is something that I have personally observed: since I began working at Hokkaido University seven years ago, the glacier that I study has lost ice equivalent to a thickness of more than 11 metres. This level of change is simply incredible.

Broken sea ice, Northwest Greenland (Photo: Evgeny Podolskiy, 2019).

I am often humbled by the grandeur of nature when in the field. Sometimes, however, I am troubled by more mundane issues: when the seas are especially choppy and the boat is rocky, I get seasick. The harsh environment also affects my work, as it is quite easy for our instruments to get lost or destroyed. This is common enough that I try to prepare internally for it, to be ready to redo my observations in the following year or two after originally planned. That said, I do enjoy my work very much, particularly the diversity inherent to it. My sensors record all acoustic waves: helicopters and boats, icebergs and whales, birds and so much more.

Message to aspiring researchersMy only advice is that life is too interesting to stay in one discipline. Being curious about new things is the best approach you can cultivate.

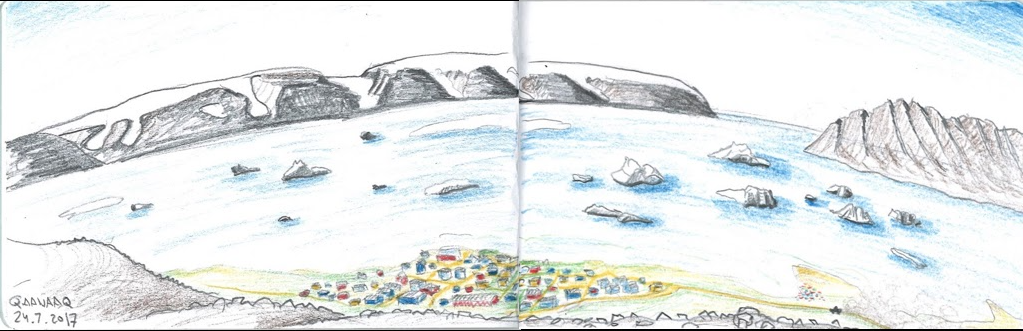

Qaanaaq — the northernmost town in Greenland, 77.5°N (sketch by Evgeny Podolskiy, 2017).

My main philosophy in research is that we are the way of the universe to look into itself, and we are made out of so many atoms which individually do not care what we are doing. As Carl Sagan, the famous space scientist, once said “We are made of star-stuff. We are a way for the universe to know itself.” I like this idea that by gaining knowledge we are recalling the previous lives of the atoms.

From IT to environmental seismo-acousticsI completed my secondary education at the Lyceum of Information Technology in Moscow—a special IT high school. As I wanted to see the world, I chose to study at the Faculty of Geography at Moscow State University. During this time, we had many opportunities to pursue internships. One of the internships I did was at mines in the Russian North. I was working on a strange issue that had come up: snow avalanches in the area seemed to prefer Fridays. This was because most mine blasting operations were carried out on Fridays, and the seismic activity caused by these operations triggered avalanches. This was the beginning of my work at the interface between glaciology and seismology, and my interest in Japan. Japan faces similar issues as there are many earthquakes and lots of snow in the country’s northern regions. I first came to Japan to pursue a Ph.D., undertook research in Europe, and finally returned to Japan to take up a position at Hokkaido University.

(Photo by Aprilia Agatha Gunawan).

Written by Sohail Keegan Pinto

Part of the special feature Understanding the Impact of Climate Change

留言 (0)