Various inflammatory and neoplastic processes can affect the nasal cavity, leading to the formation of nodular masses. Rhinoscleroma, a chronic progressive inflammatory disease of the upper respiratory tract, also belongs to this category.[1-3] It has a prolonged clinical course and passes through three distinctive but overlapping clinicopathologic stages. These are catarrhal (atrophic) stage, nodular/proliferative (granulomatous) stage, and cicatricial (sclerotic/fibrotic) stage. The proliferative stage is characterized by submucosal small, nodular, and soft lesion to begin which gradually progress to form large and firm masses.[4,5] During proliferative stage, the disease presents with characteristic a histopathologic finding.[3,6] Although nose is the most common site, involved in 95–100% of cases, this condition may rarely involve pharynx, larynx, trachea, bronchi, and adjacent areas.[1-3,6] Hence, the preferred term could be scleroma.[3] Involvement of lymph node is also a rare finding.[7] Rhinoscleroma is endemic in specific geographic areas including Southeast Asia, with frequent reports from India.[1-3,4,6,8,9] There are very few reports elaborating on the cytomorphological features of this unusual entity and are mostly based on imprint[5] and brush cytology;[6,9] however, a single case report on fine-needle aspiration cytology (FNA) of LN is also available on literature search, the authors discuss (FNA) findings in cluster of four cases of rhinoscleroma and also reviewed the existing literature.

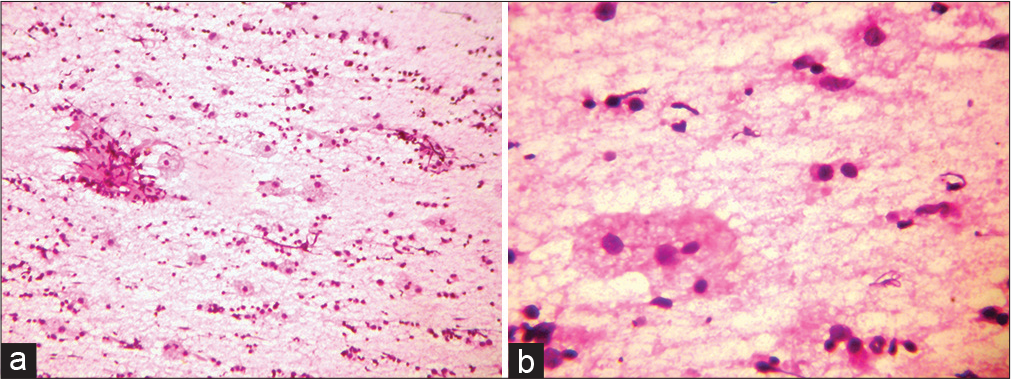

STUDY CASESThe clinical details of all four cases are tabulated in [Table 1]. In all cases, FNA was performed using 23-gauge needle attached to a 10 ml syringe, mounted on a syringe holder. The smears prepared were immediately fixed in 95% alcohol and stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) and Papanicolaou (Pap) stains while air-dried smear was stained with May-Grunwald-Giemsa (MGG). The remaining air-dried smears were retained for further special stains whenever required. All four cases showed almost similar cytomorphology comprising many histiocytes scattered singly against an inflammatory background [Figure 1a]. The histiocytes (Mikulicz cells) were large with abundant finely vacuolated to pale cytoplasm and small, uniform, round, and centric to eccentric nucleus [Figure 1b]. The inflammatory infiltrate was rich in lymphocytes and plasma cells with admixture of few eosinophils and neutrophils. Occasional proliferating fibroblasts, fibrocollagenous, and capillary fragments were also noted in the background. However, the overall cellularity, proportions of macrophages, inflammatory infiltrate, and fibrocollagenous fragments varied from case to case [Table 1].

Table 1:: Clinical details and salient cytological features in four cases of rhinoscleroma.

Features Case 1 Case 2 Case 3 Case 4 Clinical features Age (years)/Sex 19/Female 60/Male 22/Male 45/Male C/o (duration) Nasal block (2 years) Rhinorrhea and epistaxis off and on (6 months) Nasal block and epistaxis off and on (11/2 years) Nasal blockage for 3 months On examination Nasal cavity (side) Left Left Left Right Occlusion by mass Complete Partial Complete Complete Septal deviation + (to right) Absent + (to right) Left Mass Whitish-yellow, firm, extend into naso pharynx Reddish, nodular, firm Reddish, nodular, firm Large multinodular, reddish mass extend into maxillary sinus Clinical diagnosis Antrochoanal polyp Malignant tumor Nasal mass Recurrent Rhinoscleroma Cytology Cellularity ++ +++ ++ +++ Mikulicz cells + +++ ++ +++ Inflammatory cells ++ +++ ++ +++ Fibrotic fragments ++ scant + +

Figure 1:: (a) Smear showing predominantly chronic inflammatory infiltrate with singly placed large histiocytes and fibrocollagenous tissue fragment. (Fine-needle aspiration cytology [FNAC] nasal mass: H&E stain; ×20). (b) Smear shows few scattered large histiocytes with abundant pale vacuolated cytoplasm against a background of mononuclear cells. (FNAC, nasal mass: H&E stain; ×40).

Export to PPT

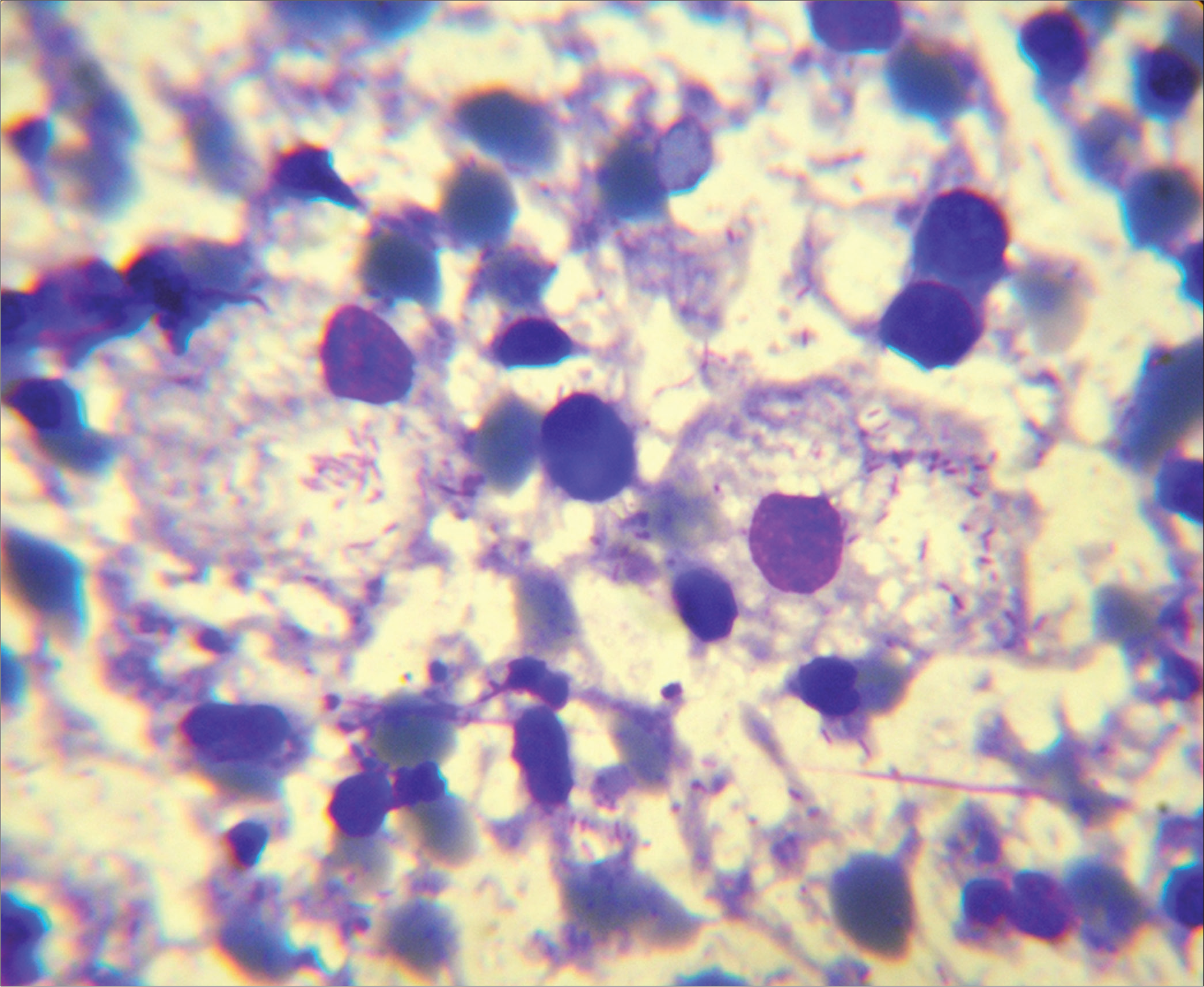

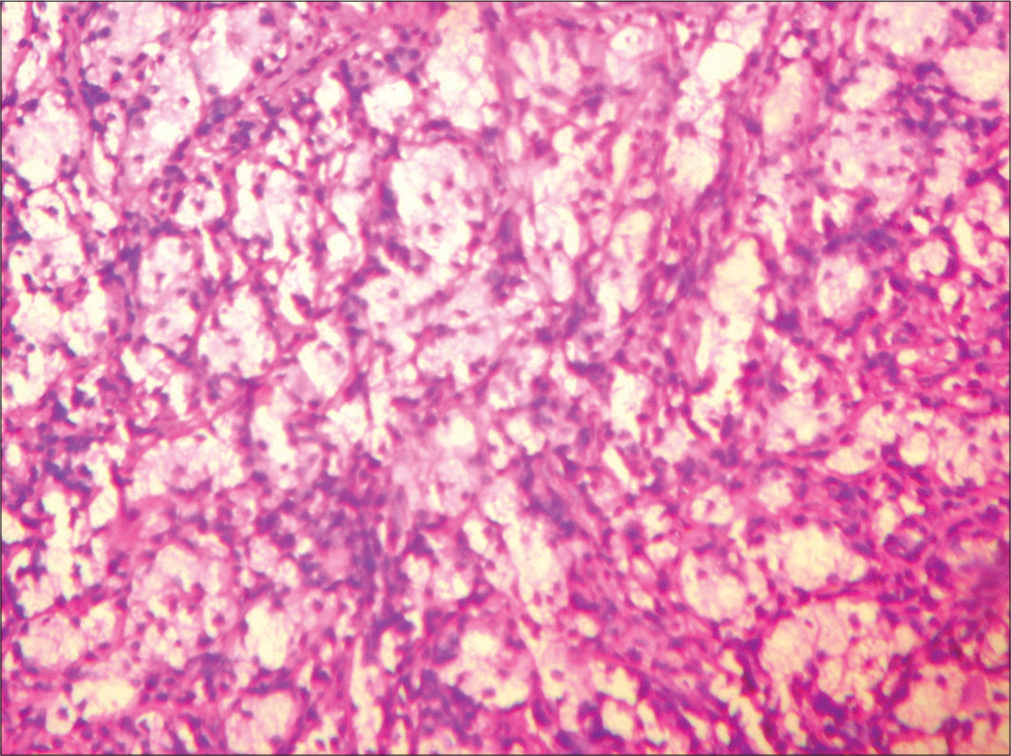

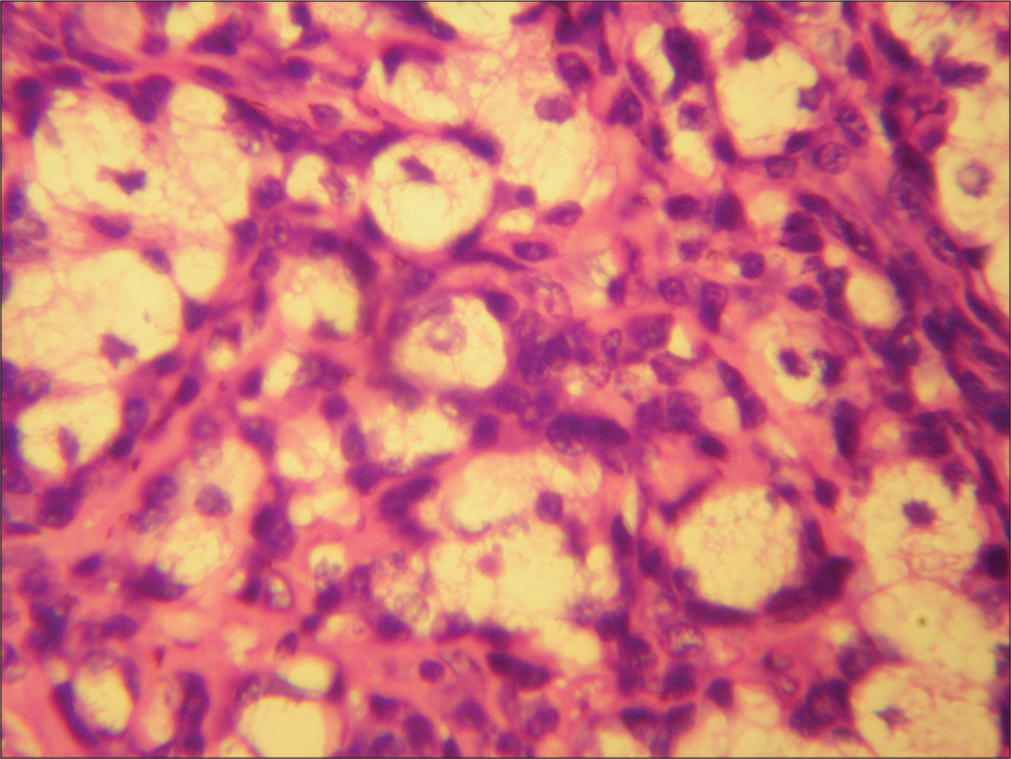

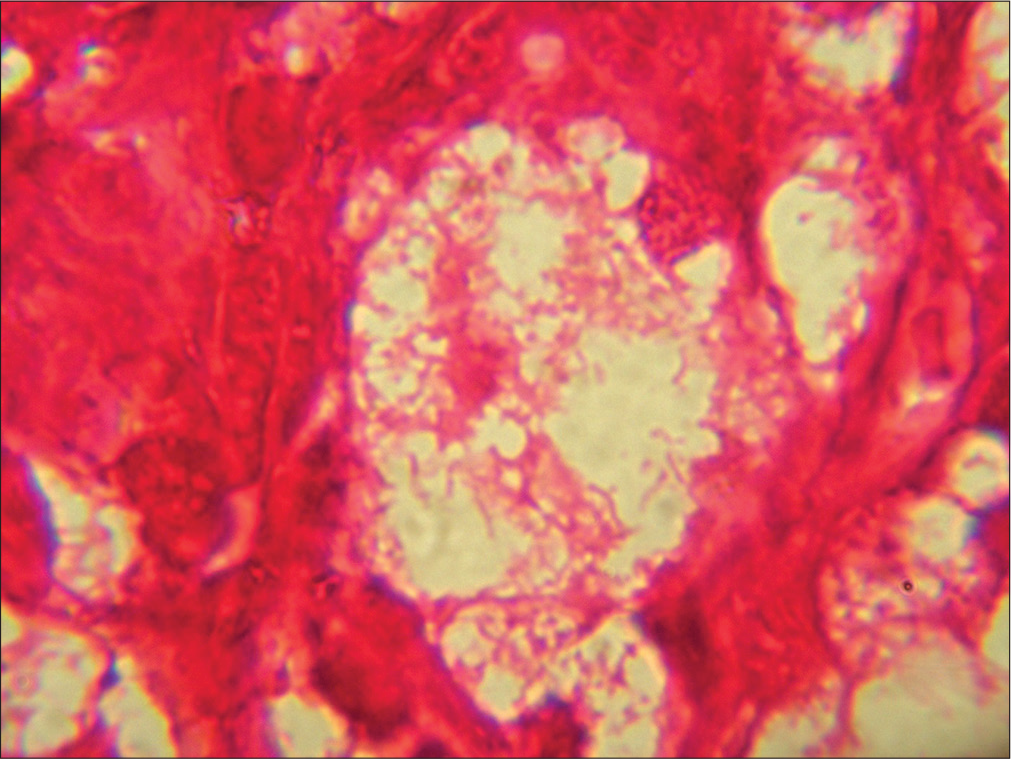

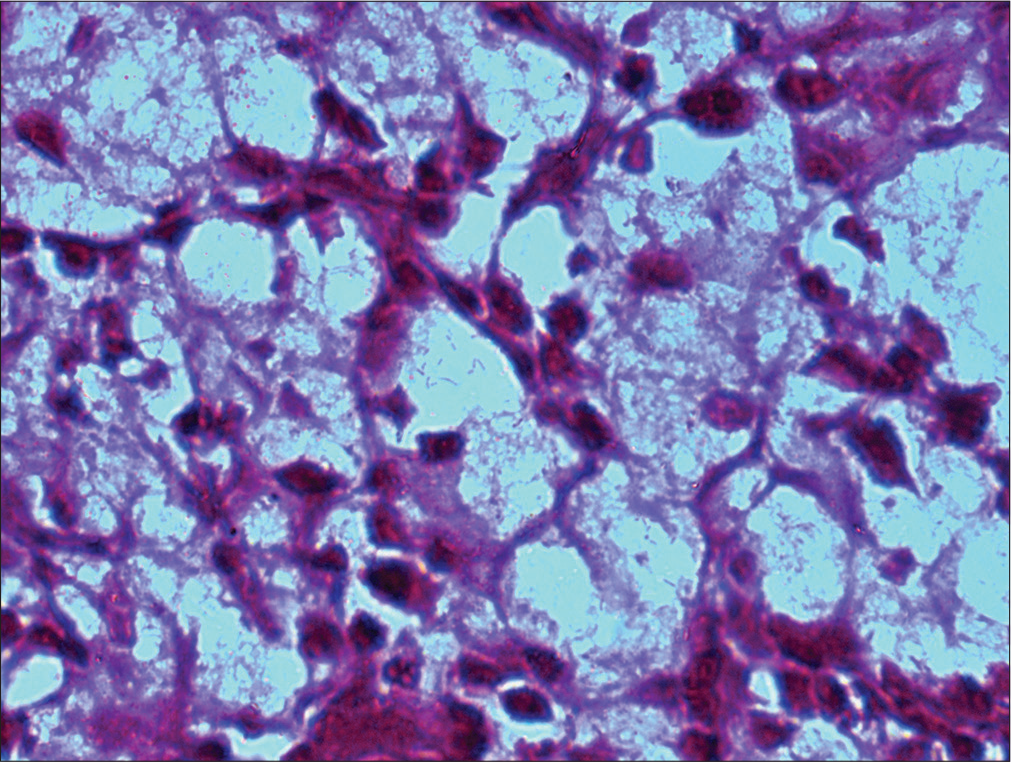

In case one, the diagnosis of lepromatous leprosy and even tuberculosis was considered. Lepromatous leprosy being the closest differential, a single retained air-dried smear was stained with modified Ziehl–Neelsen (ZN; using 5% HCl) stain which was negative for lepra bacilli. The possibility of inflammatory lesion was considered and biopsy advised. The diagnosis of rhinoscleroma was later on established on excised specimen which was supported by Gram-negative bacilli and positivity with periodic acid–Schiff (PAS) stain. Retrospectively, the cytomorphology was correlated with histopathological features. The second case displayed numerous, singly scattered histiocytes against a background of mononuclear cells. The initial diagnosis offered was of lepromatous leprosy; however, on diligent search, examination of MGG smear revealed many intracytoplasmic loosely clustered short rods in histiocytes [Figure 2]. The Gram stain further confirmed Gram-negative nature of bacilli. The diagnosis of rhinoscleroma was subsequently confirmed on histopathology which revealed polypoidal masses comprising of sheets of histiocytes separated by dense lymphoplasmacytic infiltrate [Figure 3]. On higher magnification, the histiocytes revealed abundant, pale to foamy cytoplasm with granular debris [Figure 4]. In case three, the histiocytes were comparatively fewer in number as compared to the case 2; however, knowledge about the cytomorphological features of rhinoscleroma prompted a thorough and vigilant screening of air-dried smears. The intracytoplasmic bacilli, although few, were identified in occasional histiocytes. As all smears were utilized, no special cytochemical studies could be performed and a cytodiagnosis of inflammatory lesion favoring rhinoscleroma was offered which was confirmed on histopathology. Case 4 was a known case of rhinoscleroma, presented to cytology clinic with recurrent lesion. The markedly cellular smears revealed, large number of singly scattered histiocytes against a background of dense mononuclear inflammation. The Gram-negative bacilli were well illustrated; while vague positivity was noticed on PAS stain. The excision specimen also confirmed the diagnosis of rhinoscleroma. The histochemical stains Gram [Figure 5] and PAS [Figure 6] further highlighted the morphology of bacilli.

Figure 2:: Mikulicz cells with abundant vacuolated cytoplasm containing loosely clustered short bacilli and scattered plasma cell in the background. (Fine-needle aspiration cytology, nasal mass: May-Grunewald-Giemsa stain; ×100).

Export to PPT

Figure 3:: Tissue section showing diffuse sheets histiocytes with surrounding chronic inflammatory infiltrate. (HP nasal mass: H&E stain; ×20).

Export to PPT

Figure 4:: The histiocytes show abundant foamy cytoplasm with granular intracytoplasmic debris and lymphoplasmacytic infiltrate around them. (HP nasal mass: H&E stain; ×40).

Export to PPT

Figure 5:: Intracytoplasmic Gram-negative rods in Mikulicz cells. (HP nasal mass: Gram stain; ×100).

Export to PPT

Figure 6:: Mikulicz cell shows intracytoplasmic PAS-positive rods. (HP nasal mass: PAS stain; ×100).

Export to PPT

DISCUSSIONVon Hebra and Kaposi first described rhinoscleroma, Mikulicz established its non-neoplastic, inflammatory nature while von Frisch identified causative agent as a Gram-negative Bacillus (Klebsiella rhinoscleromatis) in 1882 also called Frisch Bacillus.[1,3] It has a prolonged clinical course comprising three stages that may extend over a period of several months. Patients most commonly present with nasal airway obstruction, rhinorrhea, periodic epistaxis, and on examination, nasal mass is identified.[4] Similar clinical presentation was observed in all cases in the present study. In general, diagnosis is either made on the basis of classic histologic findings or a positive culture. However, only 50–60% of cultures are positive for K. rhinoscleromatis.[2,8] The diagnostic hallmark in its proliferative phase is large vacuolated histiocytes with intracellular short bacilli (Mikulicz cells) scattered against a rich lymphoplasmacytic background. With the beginning of sclerotic stage, and setting in of increasing fibrosis, there is a gradual reduction in number of Mikulicz cells and bacilli.[1,3,6,10] Comparison of cases in the present study revealed, prolonged duration of symptoms, in Cases 1 and 3; which might have corresponded with reduction in overall cellularity, fewer number of Mikulicz cells with intracellular organisms and more proliferating fibroblasts [Table 1]. The cellular component can therefore predict the gradual transformation from proliferative to fibrotic stage. While Cases 2 and 4 had a comparatively shorter symptomatic period and showed abundant cellularity, many Mikulicz cells, numerous intracellular organisms, and scant fibrocollagenous tissue fragments [Table 1] representing proliferative stage. Although rhinoscleroma is generally diagnosed on tissue biopsy, cytology has a definite place.[5,6,10] Among three stages, in the nodular stage, cytolomorphology is most characteristic and the lesion can easily be sampled by FNA and was possible in all four cases. The bacilli are better visualized in MGG stain and can be confirmed by histochemical stains such as Gram, PAS, Warthin-Starry stain, and also immune peroxidase techniques.[1,3,5,6,10] In Cases 2 and 3, careful screening of MGG smears helped in identification of the bacilli. In Cases 2 and 4, Gram-negative bacilli were well demonstrated. Whenever possible, it is advantageous to retain a few unstained air-dried smears for further studies, especially during FNA of intranasal masses. The clinical differentials could be rhinosporidiosis, a frequent fungal disease can reveal a non-descript chronic inflammation and characteristic large, thick-walled, spherical, and sporangia containing numerous small spores that are unmistakable.[3] The fungal infections such as candidiasis and zygomycosis can unusually involve the nose. A mixed inflammatory or granulomatous response with fungal organisms can be highlighted on special stain-like PAS or Gomori methenamine silver. The conditions such as Wegner’s granulomatosis (WG) and lethal midline granuloma can primarily be ruled out by correlating microscopic findings their aggressive clinical behavior. WG besides revealing acute and chronic inflammation also shows, necrotic debris, epithelioid cells and multinucleated giant cells; while midline lethal granuloma additionally show presence of atypical cells.[3] The cytological differentials in Indian scenario include lepromatous leprosy, atypical mycobacterial disease, mucocutaneous leishmaniasis, and sinus histiocytosis with massive lymphadenopathy (SHML). The cytologic picture in lepromatous leprosy, very closely mimic rhinoscleroma and consists many macrophages with cytoplasmic debris admixed with variable amount of chronic inflammation. However these features are to be interpreted in proper clinical context and additional histochemical stains like modified ZN, Gram stain can aid in arriving at a definitive diagnosis.[1,3] Atypical mycobacterial infection (Mycobacterium avium intracellular – MAI) of nose should also be ruled out in an immunocompromised host. It typically shows presence of many histiocytes and mononuclear inflammation and the ZN stain will reveal macrophages loaded with acid-fast bacilli.[3] In rhinoscleroma, lepromatous leprosy, and atypical mycobacterial infection, epithelioid cell transformation, or granuloma formation do not occur because of inadequate T-cell response.[1,6] Mucocutaneous leishmaniasis also known to involve nasal cavity can display Leishmania donovani (LD) bodies inside the macrophages. These are identified as intracytoplasmic, round to oval, 2–3 μ structures with small basophilic nucleus and elongated kinetoplast well visualized with Giemsa stain, as against the short rods of K. rhinoscleromatis.[10] Moreover, LD bodies do not give a positive PAS reaction.[3] SHML, a histiocyte-rich disease displays phenomenon of emperipolesis with admixture of mononuclear cells, can be a rare differential. Lack of knowledge often can delay the diagnosis, especially in non-endemic regions, and so can add on to increased morbidity. If left untreated, rhinoscleroma can cause extensive scarring, stenosis, destruction, and erosion of the upper airway resulting in nasal deformity. Treatment modalities comprise a combination of long-term systemic and local antibiotic therapy and/or surgical debridement.[2,3,8]

CONCLUSIONTo summarize, patients of rhinoscleroma in its nodular stage can present to cytology clinic for FNA sampling due to mass lesion, when the characteristic cytologic features and causative organism can best be visualized. Hence, whenever a histiocyte-rich inflammatory lesion is encountered, a diagnosis of rhinoscleroma should be included in the list of differentials for intranasal nodular lesions. High index of suspicion, diligent screening of smears, and proper and judicious use of special stains together can aid in early diagnosis of this entity even on cytology.

留言 (0)