Chronic pain is a prominent cause of disability worldwide, as well as one of the most common reasons for medical visits and absenteeism from work (Vos et al., 2012; Hoy et al., 2014). Chronic pain has several cognitive, emotional, behavioral, and functional impacts that influence the clinical course and the treatment outcome (Linton and Shaw, 2011; Giusti et al., 2020; Varallo et al., 2021b). According to the fear-avoidance model, individual who experience acute pain may get trapped in a vicious cycle of chronic incapacity and suffering due to their cognitive, emotional, behavioral, and functional responses to pain (Crombez et al., 2012). This model states that when a painful event is perceived as threatening, it can lead to catastrophizing thoughts that movement and physical activity will result in further pain and injury (Larsson et al., 2016). One component of this model includes fear of movement, or kinesiophobia, “in which a patient has an excessive, irrational, and debilitating fear of physical movement and activity resulting from a feeling of vulnerability to painful injury or re-injury” (Kori et al., 1990; Vlaeyen et al., 1995). Kinesiophobia, which affects between 51 and 72% of patients with chronic pain (Lundberg et al., 2006; Bränström and Fahlström, 2008; Perrot et al., 2018), promotes hypervigilance and worsens disability, leading to increased pain sensation (Vlaeyen and Linton, 2012). In contrast to other phobias, where individuals are generally aware of the irrationality of their fear, people with kinesiophobia believe that avoiding movement is an appropriate response, resulting in deleterious behaviors and decreased overall functional ability (Lethem et al., 1983; Desrosiers, 2018; Trinderup et al., 2018). Kinesiophobia is associated with pain intensity and disability in people suffering from chronic pain (Varallo et al., 2020, 2021a). Assessing and acting on kinesiophobia may be essential considering that physical exercise is an important component of rehabilitation treatment and high levels of kinesiophobia might compromise treatment adherence.

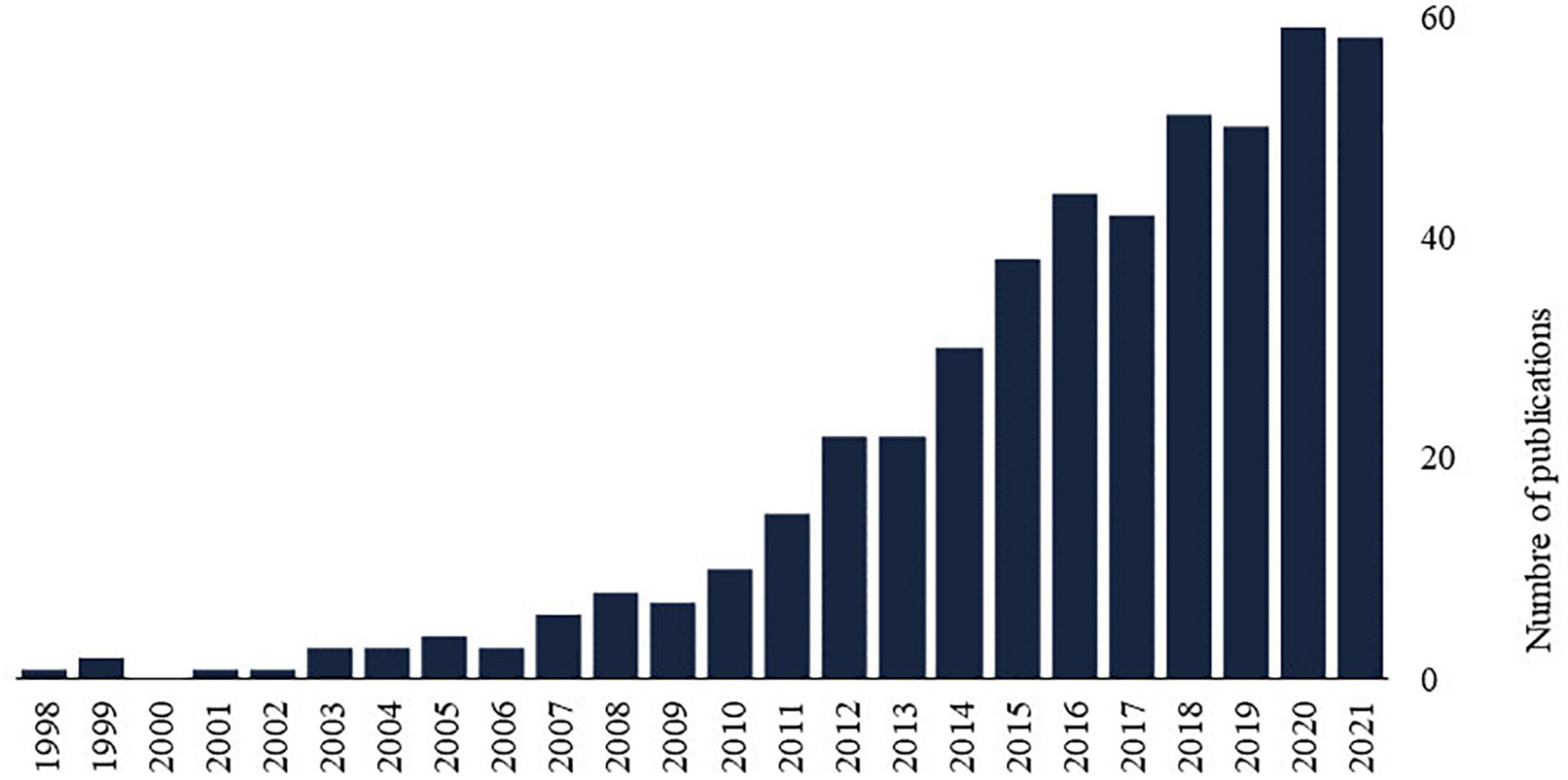

Recent years have witnessed a significant increase in the number of publications on the relationship between chronic pain and kinesiophobia (Figure 1), emphasizing the importance to investigate and synthesize research evidence on this topic. Up to now, five systematic reviews and meta-analyses, published between 2018 and 2021, have evaluated the effect of different interventions on kinesiophobia in patient with different pain conditions, including exercise training (Domingues de Freitas et al., 2020; Hanel et al., 2020), pain education (Tegner et al., 2018; Watson et al., 2019), and manual therapy (Kamonseki et al., 2021). All these reviews included articles that assessed fear of movement, regardless of whether kinesiophobia was considered a primary or secondary outcome. Given that previous reviews focused on specific interventions and/or chronic pain conditions, the goal of our scoping review was to map out the literature on treatments for kinesiophobia in people suffering from any type of chronic pain condition. A second goal of the review was to identify gaps in the literature as well as potential directions for future research. Our review questions were as follows:

• What types of interventions have been or are currently being studied in RCTs for the management of kinesiophobia in patients with chronic pain?

• What chronic pain conditions are targeted by these interventions?

• What assessment tools for kinesiophobia are used in these interventions?

FIGURE 1

Figure 1. The number of publications on chronic pain and kinesiophobia by year available on PubMed (Medline) counts all publications dates for a citation as supplied by the publisher, e.g., print and electronic publication dates. Search query: (“kinesiophobia” OR “fear of movement”) AND “chronic pain”.

Materials and methods DesignThis scoping review protocol was conducted according to the Joanna Briggs Institute Critical Appraisal tools (Peters et al., 2017) and was registered in Open Science Framework (doi: 10.17605/OSF.IO/KTJ84).1 This review is reported following Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) guidelines – extension for scoping review (Tricco et al., 2018).

Search strategyPertinent studies were extracted from CINAHL, Cochrane, Scopus, Pedro, OTseeker, AMED, OTDBASE, and Medline (PubMed) between database inception and February 15, 2022. The search strategy focused on keywords related to “pain,” “kinesiophobia,” and “randomized controlled trial.” The search strategy was reviewed by an expert librarian using the Peer Review of Electronic Search Strategies (PRESS) checklist and modified as required (McGowan et al., 2016). An example of the full search strategy is presented in Supplementary Table 1 (refer Supplementary material).

Study selectionReferences were gathered and duplicates were removed using EndNote (version X9, Thomson Reuters, 2019). In an initial screening, the references were separated into two groups of two independent reviewers (SL and MV, LS and AD) and eligible studies were selected based on titles and abstracts. In a second screening based on full texts, three groups of two independent co-authors (SL and MV, LS and AD, TB and MB) selected eligible studies. Discrepancies in these two selection steps were resolved by consensus between the two co-authors of the given group. A third independent author was consulted in the event of disagreement between these two co-authors (MB or GL).

Eligibility criteriaThe PCC approach (Population, Concept, and Context) was used to establish eligibility criteria, where “Population” referred to adults (>18 years old) with chronic pain (>3 months), “Concept” to any treatment for kinesiophobia, and “Context” to French or English peer-reviewed clinical articles from any country describing RCT conducted in any type of setting (e.g., laboratory, private clinic, rehabilitation center, hospital) with kinesiophobia as the primary outcome measure. When it was unclear whether the kinesiophobia measure was the primary outcome measure, an independent reviewer classified them according to their judgment. The presence of a comparator (no intervention, active/sham/placebo comparator) was required for study inclusion and randomized uncontrolled trials (i.e., studies comparing two experimental groups) were excluded. Studies evaluating the effects of postoperative interventions on kinesiophobia were also excluded. These studies were excluded due to the possibility that the operation would cause acute pain, eliciting a natural fear of movement during this stage of wound healing. Additionally, it is probable that these patients no longer experience pain following surgery and thus do not meet the criteria for patients with chronic pain.

Data chartingPrior to data charting, the authors developed and reviewed a comprehensive data extraction tool that included descriptions of the extraction categories. The following entries were collected:

• descriptive information about the article, including the authors, publication year, aim of the study, geographic location of the study (if not listed, location of the affiliation of the first author), study design, funding source, and study registration number;

• information regarding the participants (number of participants included in the analysis, pain condition, sex);

• information on the experimental and control interventions (description, number and duration of session, duration of the intervention, follow-up);

• information on the evaluation tool used to assess kinesiophobia.

The data were charted in Microsoft Excel (Microsoft Excel, Microsoft Corporation, Washington, United States). Data charting was completed for all included studies independently by 3 groups of 2 reviewers (SL and MV, LS and AD, TB and MB, who each charted data for one-third of the studies). Data charting files were compared between reviewers and discrepancies were resolved by consensus with a third author (GL).

Summarizing the findingsMicrosoft Excel was used to calculate descriptive statistics (e.g., totals, percentages) and to create figures to summarize the data. Descriptive information on all included studies was examined together.

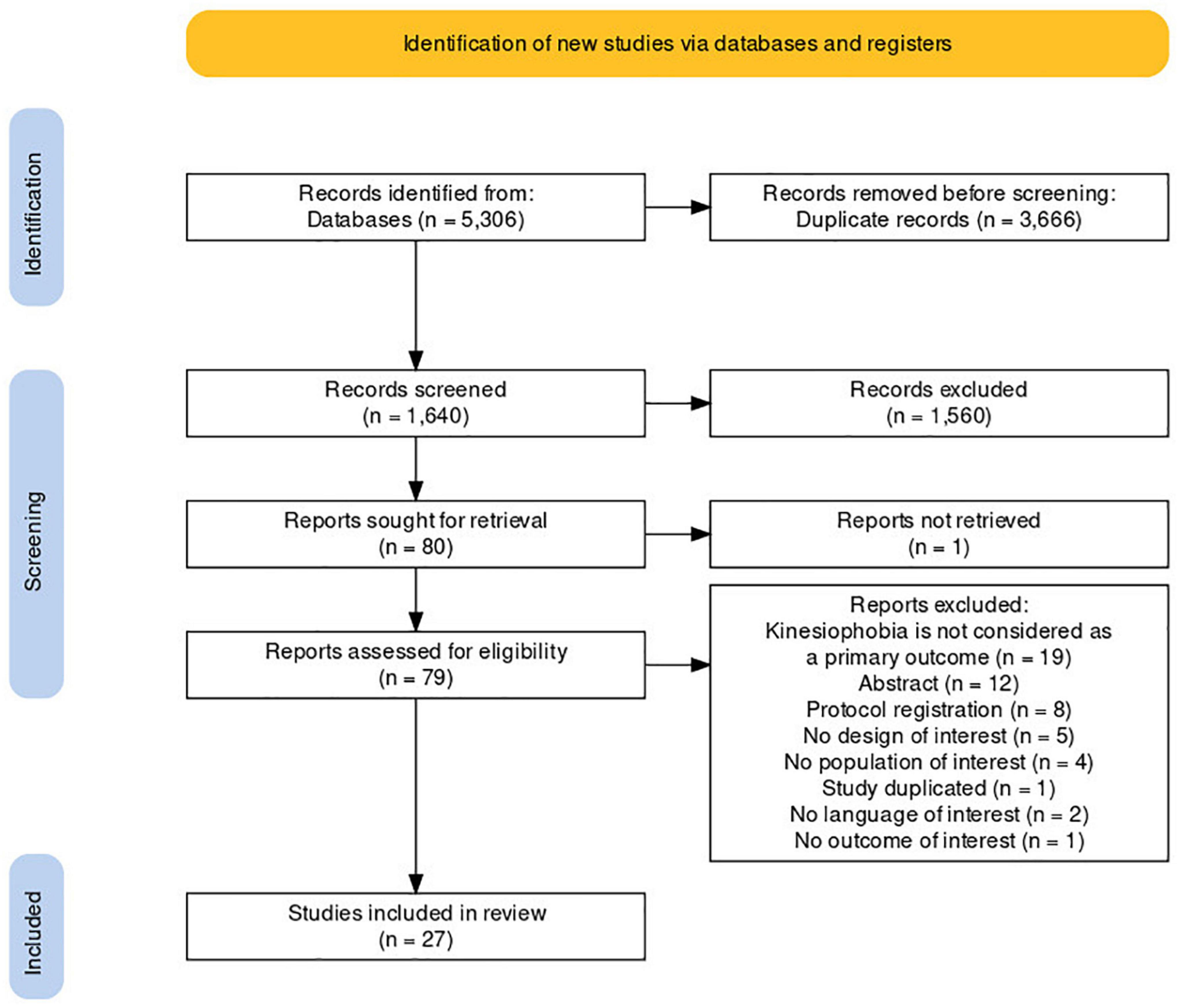

Results Article selectionOur search strategy yielded 1,640 unique citations from which 79 articles were retrieved (Figure 2). Of these, 27 studies fulfilled the selection criteria and were included in the scoping review, while 52 were excluded (Figure 2). Our extraction and analysis data sheet is available as Supplementary material.

FIGURE 2

Figure 2. Flow diagram depicting the flow of information through the various stages of the review. This figure was created by using a customizable online tool flow diagram that adheres to PRISMA 2020 standards (Haddaway et al., 2020).

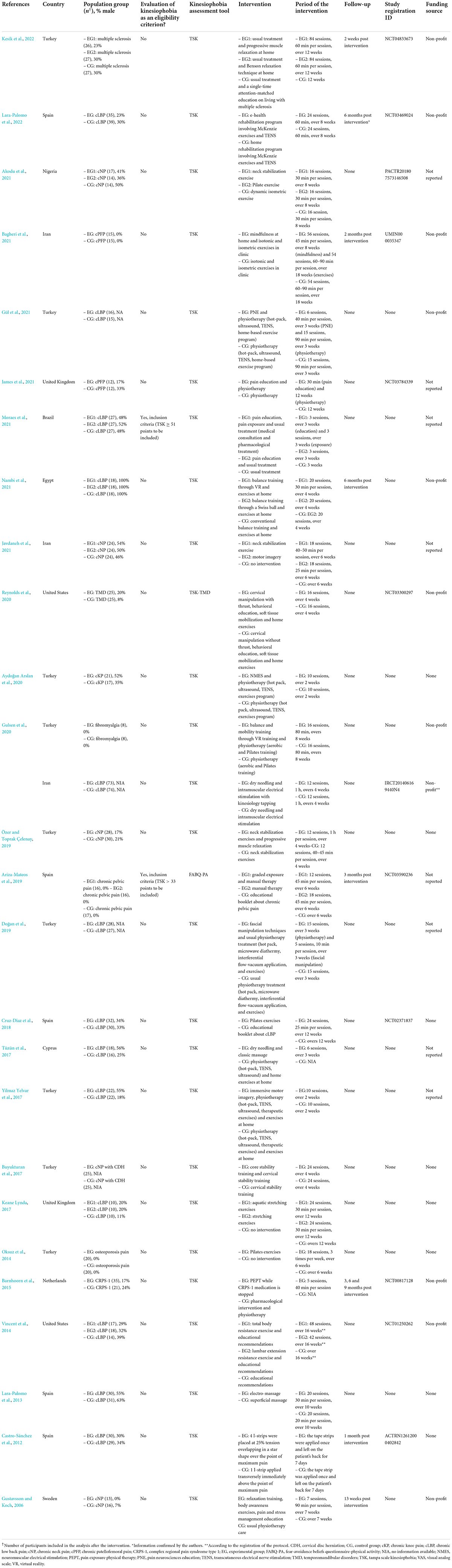

Characteristics of included studiesThe characteristics of the 27 peer-reviewed RCTs that have considered kinesiophobia as a primary outcome are summarized in Table 1. These articles included a total of 1,382 patients with chronic pain (759 included in experimental groups and 623 included in control groups), the majority of whom were women (67%). They were all published in English between 2006 and 2022 by research teams from Turkey (n = 9, 33%), Spain (n = 5, 19%), Iran (n = 3, 11%), United States (n = 2, 7%), and other countries (Cyprus, Egypt, the Netherlands, Nigeria, Sweden, United Kingdom). Eleven studies mentioned receiving funding from non-profit organizations (41%) and eight stated that they did not have a funding source (30%); this information was not provided for the remaining studies. Sixty percent of the included studies had registered their research protocol on open access web-based resources such as clinicaltrial.gov.

TABLE 1

Table 1. Characteristics of the RCT included, shown in chronological order.

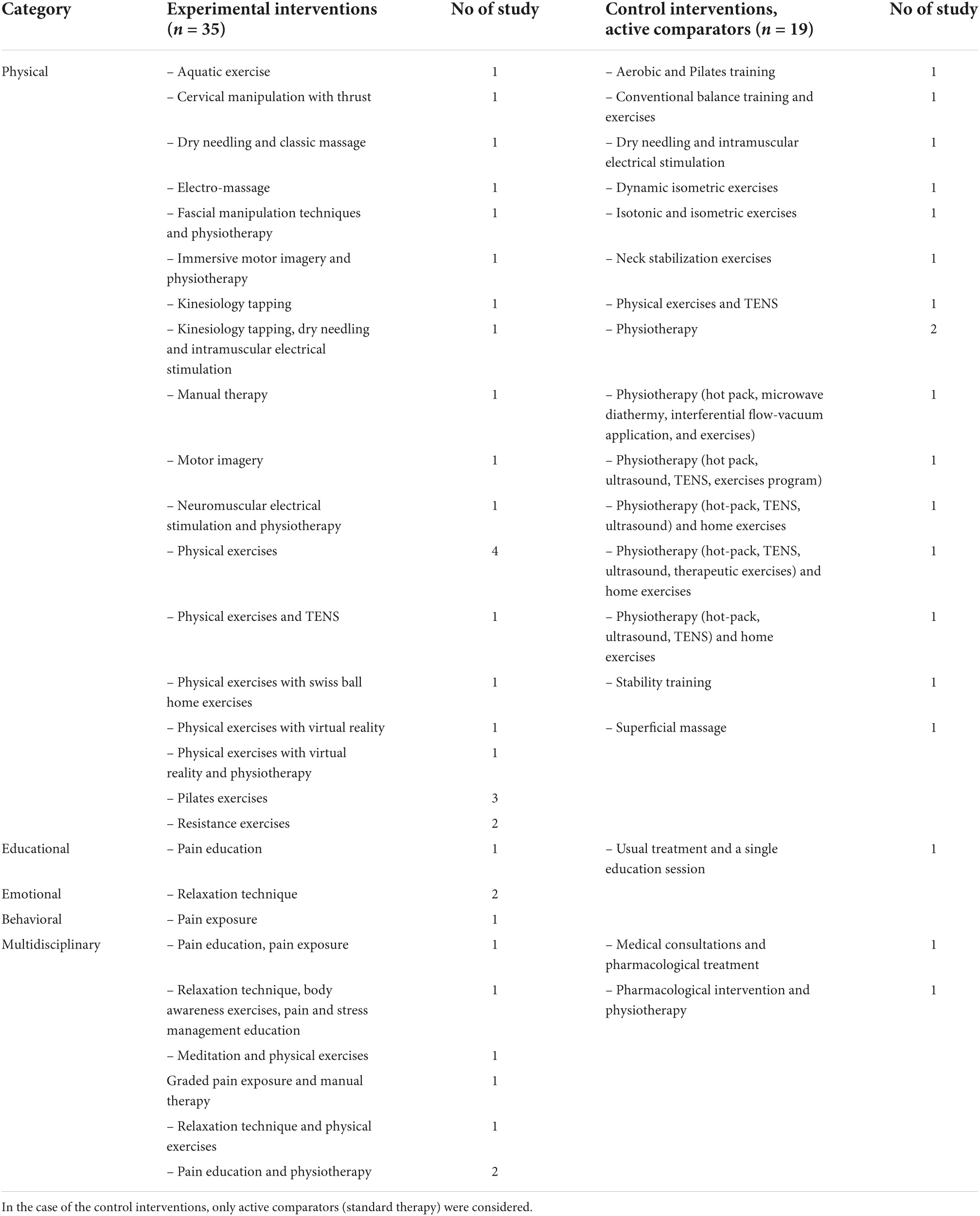

Experimental and control interventions for kinesiophobiaNineteen studies had one experimental intervention and eight studies had two, for a total of 35 experimental interventions (Table 2). These interventions were compared to sham comparator (n = 2, 7%), active comparator (n = 19, 70%), or no intervention control groups (n = 6, 22%). Of the two studies that used shams, Castro-Sánchez et al. (2012) applied kinesiology taping at the site of maximum pain in the lumbar area for both groups, which differed depending on the number of I-strips used (four for the experimental group, one for the sham group). Reynolds et al. (2020) also used a sham by performing cervical manipulations on patients with temporomandibular disorders for both groups, which differed based on the presence of high-velocity low-amplitude thrust (with thrust for the experimental group, without thrust for the sham group). As active comparators, nineteen of the included studies used standard approaches to treat kinesiophobia in patients with chronic pain (Table 2). These standard approaches included physiotherapeutic (84%), educational (5%), and multidisciplinary multimodal (11%) interventions. Experimental approaches included physiotherapeutic (69%), educational (3%), emotional (6%), psychological (3%), and multidisciplinary multimodal (20%) interventions (Table 2).

TABLE 2

Table 2. Description of experimental and control interventions among the included studies.

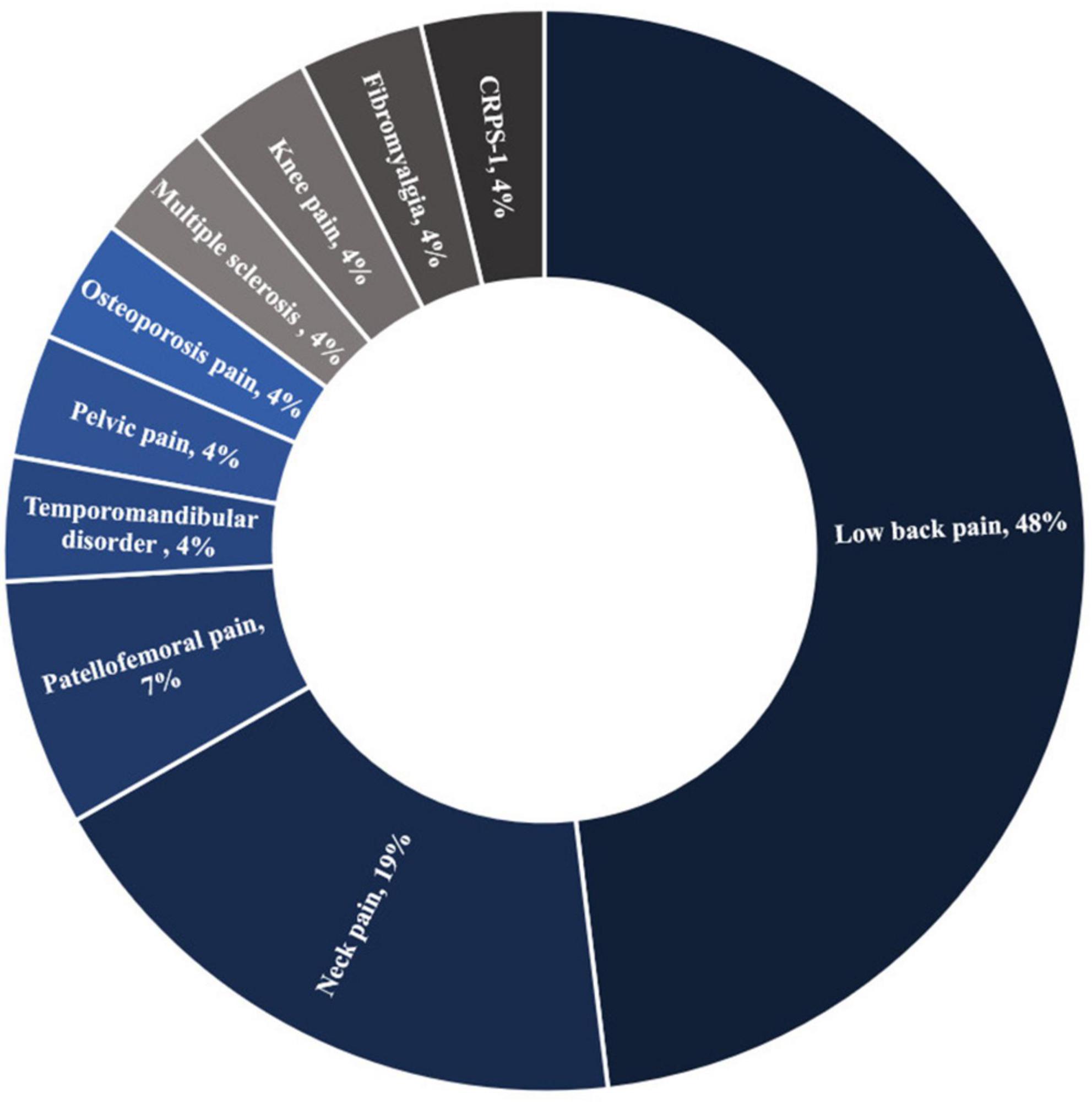

Chronic pain conditionsHalf of the patients included in this review had chronic low back pain, and one-fifth had neck pain (Figure 3). Kinesiophobia was also targeted for other chronic musculoskeletal pain disorders such as patellofemoral pain, pelvic pain, osteoporosis pain, multiple sclerosis, knee pain, fibromyalgia, complex regional pain syndrome type 1, and temporomandibular disorder (Figure 3).

FIGURE 3

Figure 3. The relative distribution of chronic pain conditions in RCTs that were included (n = 27).

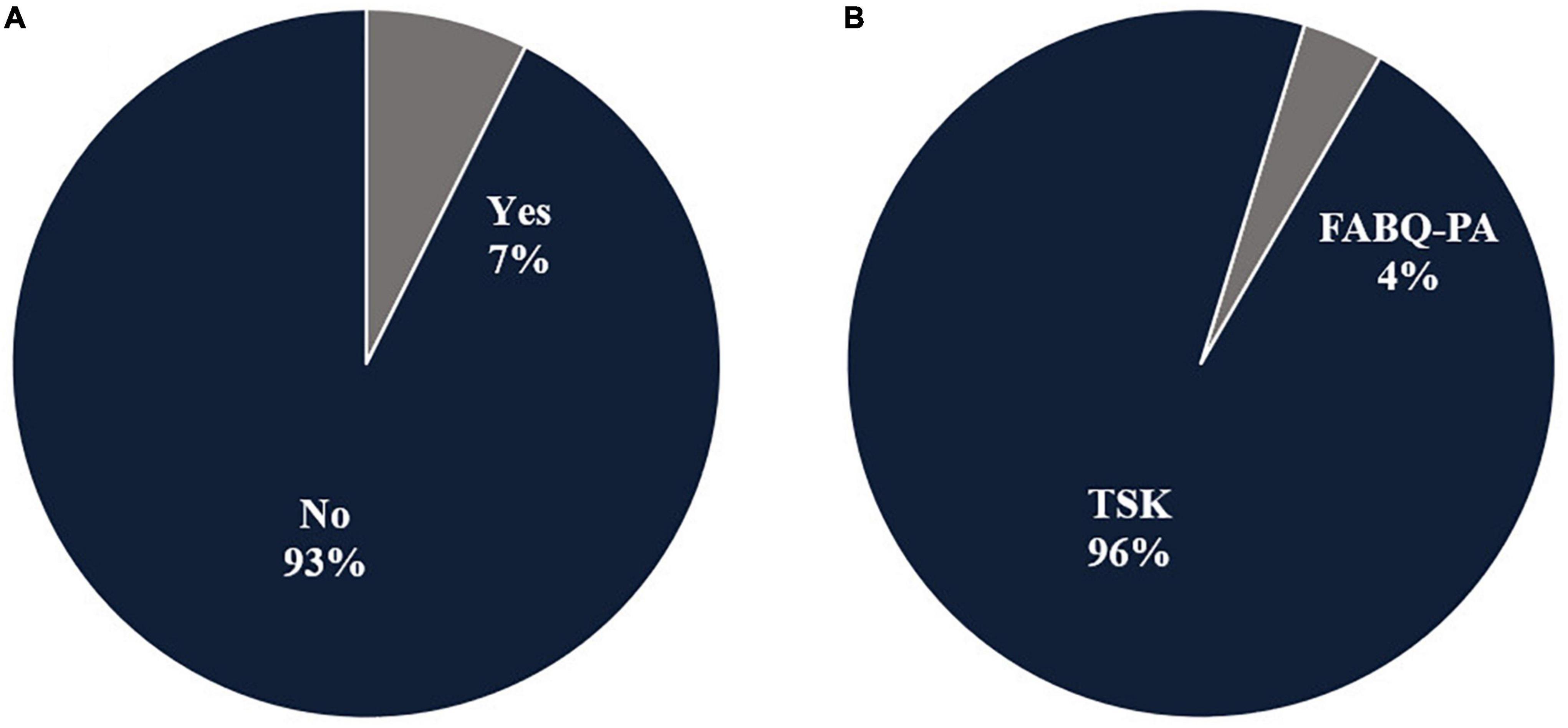

Kinesiophobia assessmentTwo studies considered kinesiophobia as an eligibility criterion (Figure 4A). Participants in the study of Ariza-Mateos et al. (2019) had to have a Tampa Scale of Kinesiophobia (TSK) score greater than 33 points, while participants in the study of Moraes et al. (2021) had to have a TSK score greater than or equal to 51 points. One study used the Fear-Avoidance Beliefs Questionnaire’s physical activity subscale to assess the effect of the interventions on kinesiophobia, Ariza-Mateos et al. (2019), while the rest of studies used the TSK (Figure 4B).

FIGURE 4

Figure 4. The relative distribution of included RCTs (n = 27) according to the following questions. (A) Was kinesiophobia a criterion for participants inclusion? (B) How is kinesiophobia measured? FABQ-PA, Fear avoidance beliefs questionnaire – physical activity scale; TSK, Tampa Scale of Kinesiophobia.

Discussion Overview of included studiesThe purpose of this scoping review was to map out the literature on therapies for kinesiophobia in patients suffering from chronic pain, as well as to identify gaps in the literature and potential directions for future investigations. Twenty-seven peers reviewed RCTs were included with a total of 1,382 chronic musculoskeletal pain patients. Thirty-five experimental interventions were compared to 27 control interventions. The initial research questions are discussed in the following paragraphs, as well as intriguing findings from the analysis.

Experimental and control interventions for kinesiophobiaThis review’s first research question was: What types of interventions have been or are currently being studied in RCTs for the management of kinesiophobia in patients with chronic pain? Our results show that exposition to physical exercises is the most used approach to dealing with irrational fear of movement. However, given that pain and kinesiophobia are phenomena having a multifactorial origin with a significant role being played by biological, psychological, and social factors (Gatchel et al., 2007; Knapik et al., 2011), “one size does not fit all” when it comes to its management. Multidisciplinary therapies have received little attention in the reviewed studies, which have mostly focused on one type of intervention at a time. However, interesting and promising multidisciplinary designs stand out. For example, Moraes et al. (2021), collaborated with nurses treating chronic low back pain patients to develop a cognitive-behavioral therapy that combines pain education, pain exposure, and standard treatment (medical consultation and pharmacological treatment). Another study by Reynolds et al. (2020) looked at the efficacy of a combination of cervical thrust manipulation, behavioral education, soft tissue mobilization, and home exercises in the treatment of temporomandibular disorder. Gustavsson and Koch (2006) provided another example with their intervention in chronic neck pain patients that combined relaxation training, body awareness exercises, and pain and stress management education.

As the use of therapeutic interventions for kinesiophobia and chronic pain grows, guidelines for their development and evaluation must be established. Every biomedical experimental intervention should go through five phases, according to the U.S. Food and Drug Administration and the National Institute of Health (U.S. Food and Drug Administration, 2006, 2018; National Institutes of Health - National Institute on Aging., 2020). Phase 0 studies use a small sample (less than 15 patients) to formulate relevant hypotheses for further research. Phase I studies evaluate a new intervention’s feasibility and initial clinical efficacy in a small group of patients (20–100). Phase II studies aim to assess a new treatment’s efficacy in a larger group of people (from 100 to 300). Phase III studies evaluate a new treatment’s efficacy in large groups of people (300–3,000) while also monitoring side effects. Finally, Phase IV trials follow thousands of volunteers for years to assess safety and long-term effects.

Non-pharmacological investigations rarely reach Phase III, most likely due to technical, human, and financial challenges associated with these types of trials. All stages of the development of a new therapeutic intervention should include direct input from patients and end-users. Failures of new interventions can be partly explained by a non-adaptation to patients’ and users’ feedback (Birckhead et al., 2019). Incorporating patients and end-users into a co-construction design process can enable researchers to increase the relevance and effectiveness of their therapy (Birckhead et al., 2019).

Chronic pain conditionsThis review’s second research question was: What chronic pain conditions are targeted by these interventions? According to our findings most scientific efforts to treat kinesiophobia have thus far focused on musculoskeletal pain conditions, particularly low back pain and neck pain, which is consistent with the results of reviews by Watson et al. (2019); Hanel et al. (2020), and Kamonseki et al. (2021). These two conditions are widespread worldwide (Vos et al., 2012; Hoy et al., 2014), and account for 70% of all years lived with disability due to musculoskeletal disorders (Vos et al., 2012), which may explain why they have been the focus of extensive research. Despite their importance, other chronic pain disorders recently associated with kinesiophobia, such as cancer pain (Van der Gucht et al., 2020), neuropathic pain (Koca et al., 2019; Herrero-Montes et al., 2022), cephalalgia and orofacial pain (Kocjan, 2017; Benatto et al., 2019; Lira et al., 2019), would deserve more research interest.

Kinesiophobia as an eligibility criterionEven if kinesiophobia was considered as a primary outcome in all included studies, only two of them considered kinesiophobia as an eligibility criterion for participants’ selection. This presents a challenge when evaluating an intervention for kinesiophobia in participants who may or may not be kinesiophobia and brings us to the point where we must emphasize how important it is for investigators to define appropriate inclusion and exclusion criteria when designing a study (Patino and Ferreira, 2018). Inclusion criteria are the key characteristics of the target population that the researchers will use to answer their research question (Patino and Ferreira, 2018). The selection of the most appropriate inclusion/exclusion criteria should follow the process of identifying the selected primary outcome measure(s) (Jones et al., 2020). This approach of selecting the inclusion/exclusion criteria based on the primary outcome measure(s) reflects the importance of ensuring that research addresses the needs and concerns of those living with condition studied (Jones et al., 2020).

Kinesiophobia assessment toolsThis review’s third research question was: What assessment tools for kinesiophobia are used in these interventions? We found that the Tampa Scale of Kinesiophobia (TSK) was the most commonly used tool to assess kinesiophobia in the reviewed studies, which is consistent with previous findings (Tegner et al., 2018; Watson et al., 2019; Martinez-Calderon et al., 2020; Kamonseki et al., 2021). Other questionnaires, such as the Kinesiophobia Causes Scale (KCS) (Knapik et al., 2011) and the NeckPix (Monticone et al., 2015), could also be used for kinesiophobia assessment. Furthermore, the Fear-Avoidance of Pain Scale (FAPS) (Crowley and Kendall, 1999), the Fear of Pain Questionnaire (FPQ) (Tella et al., 2019), the Fear-Avoidance Beliefs Questionnaire (FABQ) (Waddell et al., 1993), and the Athlete Fear-Avoidance Questionnaire (AFAQ) (Dover and Amar, 2015) are all tools with a kinesiophobia subscale. For a comprehensive comparison of these instruments, we refer the reader to the article of Liu et al. (2021). Among the included studies, only one team, Ariza-Mateos et al. (2019), used one of these tools, the FABQ with the physical activity subscale.

These different questionnaires do not necessarily have the same underlying conceptual model (Lundberg et al., 2009, 2011), which makes their psychometric properties difficult to compare. Although the TSK-17 (17 questions) is the most popular, there are some drawbacks that patients and clinicians frequently report, such as a long completion time or a lack of sensitivity (Pincus et al., 2010; Wuttke, 2021). To address these concerns, the TSK-17 has been converted into several short versions. In the TSK-11, psychometrically poor items 4, 8, 9, 12, 14, and 16 were removed (Woby et al., 2005). These items demonstrated a low correlation between the question score and the overall assessment score, and/or response trends that deviated from a normal distribution pattern (Woby et al., 2005).

Given that kinesiophobia appears to be more than a simple fear of movement, but rather the expression of a complex and multifactorial mindset stemming from the belief of fragility and susceptibility to injury (Kori et al., 1990), it seems appropriate to consider and assess this clinical measure with a tool that can address the multifactorial aspects that comprise the kinesiophobia mindset. Since 2016, a new questionnaire called the Fear-Avoidance Components Scale (FACS) is beginning to be used and seems to be the most adequate tool to date to assess multi components of fear of movement mindset, with the most comprehensive scale and good psychometric characteristics (Neblett et al., 2016; Knezevic et al., 2018; Cuesta-Vargas et al., 2020). Despite limitations in the construct and empirical supports of kinesiophobia and, more broadly, fear-avoidance, all of these tools tend to assess and characterize a mindset that is clearly predictive disability over time (Crombez et al., 2012; Wideman et al., 2013). This highlights the importance to choose the best tool according to the study population and the research question.

Interventions mainly studied in womenOur findings indicate a difference in the number of women and men who participated in the studies reviewed, with women accounting for 70% of the total sample size [refer also (Watson et al., 2019; Hanel et al., 2020; Martinez-Calderon et al., 2020)]. This difference could be explained by decades of epidemiological studies, which have reported higher prevalence of chronic pain in women compared to men for many different pain conditions (Rasmussen et al., 1991; Wolfe et al., 1995; LeResche, 1997; Bouhassira et al., 2008; Fillingim et al., 2009; Etherton et al., 2014; Mathieu et al., 2020). Sex disparities in pain experience have also been well documented, with women reporting more severe pain, at a higher frequency and greater duration on average, compared to men (Unruh, 1996). The actual literature is not successful in producing a clear and consistent pattern to explain these sexual dimorphisms in human pain sensitivity, possibly due to the multiple biological, psychosocial, and social factors interacting together to influence ascending and descending pain mechanisms (Popescu et al., 2010; Racine et al., 2012; Bartley and Fillingim, 2013).

LimitsThis review was limited to RCT. Due to publication bias; our review may also be unrepresentative of all completed studies. Indeed, our search strategy yielded a number of preliminary works presented in abstracts and clinical trial protocols, the results of which have not yet been published in peer-reviewed scientific journals (38% of excluded references). Moreover, an important difference among experimental and control interventions across studies is also important to consider in this review. Such issue stem in part from the fact that several research teams cannot afford iterative research development, challenging methodological consistency and replication.

Recommendations for future studiesThe relatively small number of RCTs identified regarding the broad field of kinesiophobia in adults with chronic pain highlights the importance of conducting future studies in this area. This relatively new field would benefit from replication and standardization as part of a theoretical framework to enable reflective and purposeful progress. A consensus on the best co-constructive research method for developing and evaluating new interventions for kinesiophobia within a scientific framework is required as guidelines developed for pharmacological studies are not the best suited for non-pharmacological trials. New RCTs evaluating person-centered, multidisciplinary intervention that takes into consideration the patient’s biological, psychological, and social experiences with pain and kinesiophobia are also required.

The different kinesiophobia assessment tools should be considered when designing a study, and the combination of several questionnaires should be considered, when necessary (Liu et al., 2021). Future studies should recruit a similar number of men and women to determine the effect of biological sex on the kinesiophobia intervention. Special attention should also be given to the various pathologies associated with chronic pain and kinesiophobia, other than chronic low back pain and chronic neck pain. Finally, authors of future studies should report their trial findings following standardized guidelines statements, such as the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) for RCTs (Schulz et al., 2010) to facilitate the replicability of studies and the advancement of knowledge in the field.

ConclusionAccording to this scoping review of RCTs, the exposition to physical exercises is the most used approach to dealing with irrational fear of movement, and the Tampa Scale of Kinesiophobia is the most used tool to measure kinesiophobia. Management of kinesiophobia has so far largely focused on patients with musculoskeletal pain, particularly low back pain and neck pain. Future RCTs should consider the level of kinesiophobia as an eligibility criterion, as well as multidisciplinary interventions that can help patients confront their irrational fear of movement while considering the patient’s personal biological, psychological, and social experiences with pain and kinesiophobia.

Author contributionsMB drafted the data collection tools, performed the literature search, participated and oversaw the data collection, analyzed the data, and wrote the first draft of the manuscript. AD, MV, SL, LS, and TB worked together to classify the references and to the data charting. MV assisted with data analysis. MV and AD assisted with the first draft of the manuscript. All authors contributed to the study’s design, development of the data collection tool, and manuscript revision and agreed on the final version of the submitted manuscript.

FundingWith the financial support of the European Regional Development Fund (Interreg FWVl NOMADe N° 4.7.360, for TL, NR, and SL), the Fonds de recherche – Santé (Clinical Research Scholars Junior 2 for GL, and doctoral scholarship for MV), Lucine and the Centre de Recherche sur le Vieillissement (postdoctoral scholarship for MB, doctoral scholarship for AD).

AcknowledgmentsWe thank Julie Mayrand, librarian at Sherbrooke University’s Health Sciences Library, for conducting the PRESS analysis of the search strategy.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s noteAll claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary materialThe Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fnbeh.2022.933483/full#supplementary-material

Footnotes ^ https://osf.io/ktj84 ReferencesAkodu, A. K., Nwanne, C. A., and Fapojuwo, O. A. (2021). Efficacy of neck stabilization and Pilates exercises on pain, sleep disturbance and kinesiophobia in patients with non-specific chronic neck pain: A randomized controlled trial. J. Bodyw. Mov. Ther. 26, 411–419. doi: 10.1016/j.jbmt.2020.09.008

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Ariza-Mateos, M. J., Cabrera-Martos, I., Ortiz-Rubio, A., Torres-Sánchez, I., Rodríguez-Torres, J., and Valenza, M. C. (2019). Effects of a patient-centered graded exposure intervention added to manual therapy for women with chronic pelvic pain: A randomized controlled trial. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 100, 9–16. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2018.08.188

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Aydoğan Arslan, S., Demirgüç, A., Kocaman, A., and Keskin, E. (2020). The effect of short-term neuromuscular electrical stimulation on pain, physical performance, kinesiophobia, and quality of life in patients with knee osteoarthritis. Physiotherapyq 28, 31–37. doi: 10.5114/pq.2020.92477

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Bagheri, S., Naderi, A., Mirali, S., Calmeiro, L., and Brewer, B. W. (2021). Adding mindfulness practice to exercise therapy for female recreational runners with patellofemoral pain: A randomized controlled trial. J. Athl. Train. 56, 902–911. doi: 10.4085/1062-6050-0214.20

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Barnhoorn, K. J., Staal, J. B., van Dongen, R. T., Frölke, J. P., Klomp, F. P., van de Meent, H., et al. (2015). Are pain-related fears mediators for reducing disability and pain in patients with complex regional pain syndrome type 1? An explorative analysis on pain exposure physical therapy. PLoS One 10:e0123008. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0123008

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Benatto, M. T., Bevilaqua-Grossi, D., Carvalho, G. F., Bragatto, M. M., Pinheiro, C. F., Straceri Lodovichi, S., et al. (2019). Kinesiophobia Is Associated with Migraine. Pain Med. 20, 846–851. doi: 10.1093/pm/pny206

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Birckhead, B., Khalil, C., Liu, X., Conovitz, S., Rizzo, A., Danovitch, I., et al. (2019). Recommendations for methodology of virtual reality clinical trials in health care by an international working group: Iterative study. JMIR Ment. Health 6:e11973. doi: 10.2196/11973

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Bouhassira, D., Lanteri-Minet, M., Attal, N., Laurent, B., and Touboul, C. (2008). Prevalence of chronic pain with neuropathic characteristics in the general population. Pain 136, 380–387. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2007.08.013

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Bränström, H., and Fahlström, M. (2008). Kinesiophobia in patients with chronic musculoskeletal pain: Differences between men and women. J. Rehabil. Med. 40, 375–380. doi: 10.2340/16501977-0186

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Buyukturan, B., Guclu - Gunduz, A., Buyukturan, O., Dadali, Y., Bilgin, S., and Kurt, E. E. (2017). Cervical stability training with and without core stability training for patients with cervical disc herniation: A randomized, single-blind study. Eur. J. Pain 21, 1678–1687. doi: 10.1002/ejp.1073

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Castro-Sánchez, A. M., Lara-Palomo, I. C., Matarán- Peñarrocha, G. A., Fernández-Sánchez, M., Sánchez-Labraca, N., and Arroyo-Morales, M. (2012). Kinesio taping reduces disability and pain slightly in chronic non-specific low back pain: A randomised trial. J. Physiother. 58, 89–95. doi: 10.1016/S1836-9553(12)70088-7

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Crombez, G., Eccleston, C., Van Damme, S., Vlaeyen, J. W. S., and Karoly, P. (2012). Fear-avoidance model of chronic pain: The next generation. Clin. J. Pain 28, 475–483. doi: 10.1097/AJP.0b013e3182385392

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Crowley, D., and Kendall, N. A. S. (1999). Development and initial validation of a questionnaire for measuring fear-avoidance associated with pain: The fear-avoidance of pain scale. J Musculoskelet. Pain 7, 3–19. doi: 10.1300/J094v07n03_02

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Cruz-Diaz, D., Romeu, M., Velasco-Gonzalez, C., Martinez-Amat, A., and Hita-Contreras, F. (2018). The effectiveness of 12 weeks of Pilates intervention on disability, pain and kinesiophobia in patients with chronic low back pain: A randomized controlled trial [with consumer summary]. Clin. Rehabil. 32, 1249–1257. doi: 10.1177/0269215518768393

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Cuesta-Vargas, A. I., Neblett, R., Gatchel, R. J., and Roldán-Jiménez, C. (2020). Cross-cultural adaptation and validity of the Spanish fear-avoidance components scale and clinical implications in primary care. BMC Fam. Pract. 21:44. doi: 10.1186/s12875-020-01116-x

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Desrosiers, M. (2018). KINAP Évaluation de la kinésiophobie; Guide de l’intervenant. Québec: Centre intégré universitaire de santé et de services sociaux (CIUSSS) de la Capitale-Nationale.

Doğan, B. E., Bayramlar, K., and Turhan, B. (2019). Investigation of fascial treatment effectiveness on pain, flexibility, functional level, and kinesiophobia in patients with chronic low back pain. Physiotherapyq 27:1. doi: 10.5114/pq.2019.86461

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Domingues de Freitas, C., Costa, D. A., Junior, N. C., and Civile, V. T. (2020). Effects of the pilates method on kinesiophobia associated with chronic non-specific low back pain: Systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Bodyw. Mov. Ther. 24, 300–306. doi: 10.1016/j.jbmt.2020.05.005

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Etherton, J., Lawson, M., and Graham, R. (2014). Individual and gender differences in subjective and objective indices of pain: Gender, fear of pain, pain catastrophizing and cardiovascular reactivity. Appl. Psychophysiol. Biofeedback 39, 89–97. doi: 10.1007/s10484-014-9245-x

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Fillingim, R. B., King, C. D., Ribeiro-Dasilva, M. C., Rahim-Williams, B., and Riley, J. L. III (2009). Sex, gender, and pain: A review of recent clinical and experimental findings. J. Pain 10, 447–485. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2008.12.001

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Gatchel, R. J., Peng, Y. B., Peters, M. L., Fuchs, P. N., and Turk, D. C. (2007). The biopsychosocial approach to chronic pain: Scientific advances and future directions. Psychol. Bull. 133, 581–624. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.133.4.581

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Giusti, E. M., Manna, C., Varallo, G., Cattivelli, R., Manzoni, G. M., Gabrielli, S., et al. (2020). The predictive role of executive functions and psychological factors on chronic pain after orthopaedic surgery: A longitudinal cohort study. Brain Sci. 10:685. doi: 10.3390/brainsci10100685

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Gül, H., Erel, S., and Toraman, N. F. (2021). Physiotherapy combined with therapeutic neuroscience education versus physiotherapy alone for patients with chronic low back pain: A pilot, randomized-controlled trial. Turk J. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 67, 283–290. doi: 10.5606/tftrd.2021.5556

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Gulsen, C., Soke, F., Eldemir, K., Apaydin, Y., Ozkul, C., Guclu-Gunduz, A., et al. (2020). Effect of fully immersive virtual reality treatment combined with exercise in fibromyalgia patients: A randomized controlled trial. Assist. Technol. 34, 256–263. doi: 10.1080/10400435.2020.1772900

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Gustavsson, C., and Koch, Lv (2006). Applied relaxation in the treatment of long-lasting neck pain: A randomized controlled pilot study. J. Rehabil. Med. 38, 100–107. doi: 10.1080/16501970510044025

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Hanel, J., Owen, P. J., Held, S., Tagliaferri, S. D., Miller, C. T., Donath, L., et al. (2020). Effects of exercise training on fear-avoidance in pain and pain-free populations: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Sports Med. 50, 2193–2207. doi: 10.1007/s40279-020-01345-1

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Herrero-Montes, M., Fernández-de-las-Peñas, C., Ferrer-Pargada, D., Tello-Mena, S., Cancela-Cilleruelo, I., Rodríguez-Jiménez, J., et al. (2022). Prevalence of neuropathic component in post-COVID pain symptoms in previously hospitalized COVID-19 survivors. Int. J. Clin. Pract. 2022:3532917. doi: 10.1155/2022/3532917

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Hoy, D., March, L., Brooks, P., Blystartrth, F., Woolf, A., Bain, C., et al. (2014). The global burden of low back pain: Estimates from the Global Burden of Disease 2010 study. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 73, 968–974. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2013-204428

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

James, J., Selfe, J., and Goodwin, P. (2021). Does a bespoke education session change levels of catastrophizing, kinesiophobia and pain beliefs in patients with patellofemoral pain? A feasibility study. Physiother. Pract. Res. 42, 153–163. doi: 10.3233/PPR-210529

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Javdaneh, N., Molayei, F., and Kamranifraz, N. (2021). Effect of adding motor imagery training to neck stabilization exercises on pain, disability and kinesiophobia in patients with chronic neck pain [with consumer summary]. Complement. Ther. Clin. Pract. 42:101263. doi: 10.1016/j.ctcp.2020.101263

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Jones, A. P., Clayton, D., Nkhoma, G., Sherratt, F. C., Peak, M., Stones, S. R., et al. (2020). “Choosing a patient-important primary outcome measure,” in Different corticosteroid induction regimens in children and young people with juvenile idiopathic arthritis: The SIRJIA mixed-methods feasibility study (Southampton: NIHR Journals Library). doi: 10.3310/hta24360

留言 (0)