Dear Editor,

Atopic dermatitis is a chronic pruritic dermatosis with a huge psychosocial burden.1 Constant scratching, particularly in patients with skin of colour, often causes dyspigmentation, both hyperpigmentation and sometimes depigmentation, especially in lichenified skin.2 This further negatively impacts the quality of life.

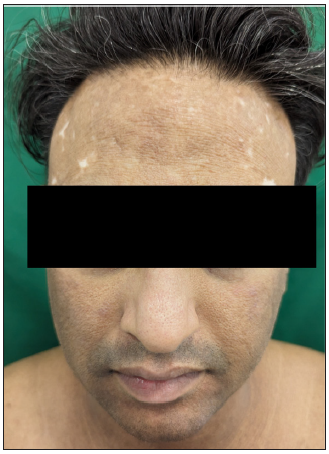

A 36-year-old man, with childhood-onset atopic dermatitis presented with involvement of the face, neck, and upper trunk in the form of hyperpigmented lichenified plaques, linear excoriations, and pronounced fissuring [Figure 1a]. Notably, conspicuous depigmented plaques were present bilaterally on the sides of the forehead, accompanied by smaller macules centrally, encroaching upon the anterior hairline. Prior to the development of these, the patient reported similar hyperpigmented lichenified plaques, and no depigmented macules were noted elsewhere on the body. Dennie-morgan folds, dirty neck, and palmar hyperlinearity were also present. The patient reported transient symptomatic amelioration with oral corticosteroids; nonetheless, disease relapse promptly followed treatment cessation. No history of hair dye usage was elicited, eliminating it as a potential causative agent for the depigmentation.

Export to PPT

We started the patient on oral tofacitinib 5 mg twice daily, oral steroid minipulse therapy (5 mg betamethasone) two days/week, antihistamines, tacrolimus ointment (for face), topical mometasone cream and liberal application of paraffin-based moisturiser.

At the subsequent visit, there was a marked reduction in pruritus and excoriations had healed. A gradual tapering of betamethasone allowed its complete discontinuation over 6 months. He was then maintained on tofacitinib for another three months, which led to a notable improvement in the lichenified plaques on the face. Nonetheless, the depigmentation persisted [Figure 1b].

Export to PPT

We planned a non-cultured epidermal suspension (NCES) for these depigmented areas. A thin epidermal graft was harvested from the uninvolved left lateral thigh (donor site) and subjected to warm trypsinisation (0.25% trypsin). The dermis was separated from the epidermis followed by teasing out of the pigmented cells. The recipient area was prepared by gentle dermabrasion, extending just beyond the depigmented margin. Post-centrifugation of the melanocyte-rich cell suspension, the pellet was re-suspended in phosphate-buffered saline and transferred to the recipient site.

Following the procedure, the patient was instructed to continue the application of topical tacrolimus on the face. Approximately a month later, we observed islands of normally pigmented skin emerging within the previously depigmented areas. Subsequently, there was a near-complete repigmentation at three months, and this outcome was sustained even at the nine-month follow-up [Figure 1c]. The patient was also highly satisfied with the treatment.

Export to PPT

Alteration in neurotrophic polypeptides, such as nerve growth factor (NGF) is a feature of many chronic inflammatory dermatoses, including atopic dermatitis.3 NGF plays a pivotal role in both neuronal differentiation and also in influencing the survival of melanocytes through its interaction with tyrosine kinase receptors.4,5 In lichenified lesions, there is a reduced NGF production by keratinocytes and also a reduction in length and number of peripheral nerve fibres in the leukoderma areas compared to non-leukoderma areas.2 The decreased NGF production, in turn, triggers a reduction in melanocytes. A similar depigmentation has been reported in lichen simplex chronicus and also in severe atopic dermatitis (‘vitiligoid achromias’).2,6 The presence of depigmented macules localised to sites initially affected by severe eczema and did not show further progression, differentiating it from vitiligo.6

The present case showed remarkable repigmentation with NCES, which relies on the principle of transfer of autologous melanocytes from normal pigmented donor skin. NCES has shown to be effective in various non-vitiligo causes of leukoderma like naevus depigmentosus, piebladism, chemical leukoderma, and halo naevus, with results comparable to vitiligo (>75% repigmentation in 27%–100% of patients). Segmental vitiligo and piebaldism had the highest regimentation rates.7

While vitiligo may co-exist with atopic dermatitis, however, the localisation of the depigmentation only on the forehead does not conform with any known patterns of non-segmental vitiligo. Moreover, these depigmented areas had been preceded by hyperpigmented lichenified plaques.

We cannot dismiss the potential immunomodulatory effects of tofacitinib and oral steroids in atopic dermatitis; however, it is essential to note that there was no repigmentation observed during the six-month period when both modalities were used concurrently before implementing NCES.

留言 (0)